Pittsburgh has spent almost $8.5 million on a gunshot-detection system called ShotSpotter over the past 10 years. The city’s contract with SoundThinking, ShotSpotter’s California-based parent company, is set to expire at the end of 2025.

Supporters claim ShotSpotter allows police to arrive at crime scenes sooner, which leads to more arrests in gun-related crimes and gunshot victims getting help faster. Critics question its effectiveness and raise concerns about mass surveillance in Black neighborhoods and increasing bias in policing.

With Pittsburgh City Council preparing to discuss whether to renew the ShotSpotter contract, we analyzed an August 2025 audit of the system by City Controller Rachael Heisler’s office. Despite the report’s positive tone, a closer look prompted several disturbing questions.

How (and why) is ShotSpotter being compared to 911 emergency services?

Ms. Heisler’s report fails to address whether ShotSpotter has reduced gun violence, instead evaluating the system against 911. The report’s first result is that “ShotSpotter alerts tend to be just as productive as 911 calls.” Considering ShotSpotter’s $1.2 million per year price tag, shouldn’t the results be more solidly favorable compared to a service the city is not paying for?

In Pennsylvania, the 911 system is run by counties and funded with a statewide $1.95 surcharge on monthly phone bills or, for pre-paid phones, at the point of sale.

How often does ShotSpotter cause Pittsburgh police to respond to false alarms?

Ms. Heisler’s report did not include documentation of ShotSpotter’s false alarm rate, but the system has been known to classify fireworks or other loud sounds as gunfire. This increases the likelihood of wasting emergency resources. Pittsburgh’s police scanner logs reveal multiple examples of false alarms from sources including roofing work; gas explosions; and tires, balloons, or plastic soda bottles popping.

Why have 911 calls in Pittsburgh dropped by 50%?

The biggest mystery comes from the report’s assertion that, “Following the deployment of ShotSpotter, 911 calls decreased dramatically, a 50% drop from 2014.” The report does not list decreasing 911 calls as a goal of using ShotSpotter, but it does refer to the decrease as a “result.”

It seems unlikely that the reasons for 911 calls have undergone an equally dramatic decline. So it’s hard to see this finding in a positive light.

One clue lies in the report’s comparison of 911 and ShotSpotter response times. Charts 9 and 10 on page 16 show ShotSpotter significantly outperforming 911 in this area, although ShotSpotter’s response times got longer each year.

A pair of audits released by Ms. Heisler’s office and Allegheny County Controller Corey O’Connor’s office in September pointed out slowing response times for police and emergency medical services. They recommended increased staffing for the county’s 911 call center and improvements to programs that ensure first responders’ well-being.

While Ms. Heisler’s ShotSpotter report suggests the technology is cutting police response times, a study from the University of California Santa Barbara Economics Department concluded that ShotSpotter dispatches take away from the time police have to respond to 911 calls—effectively worsening their response times to calls of distress made by residents.

These are questions that should be answered before Pittsburgh commits to another long and expensive contract for ShotSpotter.

Questionable benefits, documented harms

According to SoundThinking’s website, more than 180 cities have purchased ShotSpotter. While some cities, like Pittsburgh, have stuck with the technology, others canceled their ShotSpotter contracts or chose not to renew them because of cost, a low confirmation of shootings, and a lack of effect on gun violence.

The most pressing concern about ShotSpotter is that it deepens racial bias in policing. In 2024, Chicago ended its relationship with ShotSpotter after years of controversy and high-profile tragedies. In 2021, a 13-year-old boy named Adam Toledo was chased, shot and killed by a Chicago police officer responding to a ShotSpotter alert. A lawsuit filed against the City of Chicago around misuses of ShotSpotter names Danny Ortiz, a 36-year-old father who was arrested and jailed by police who searched him while responding to a ShotSpotter alert.

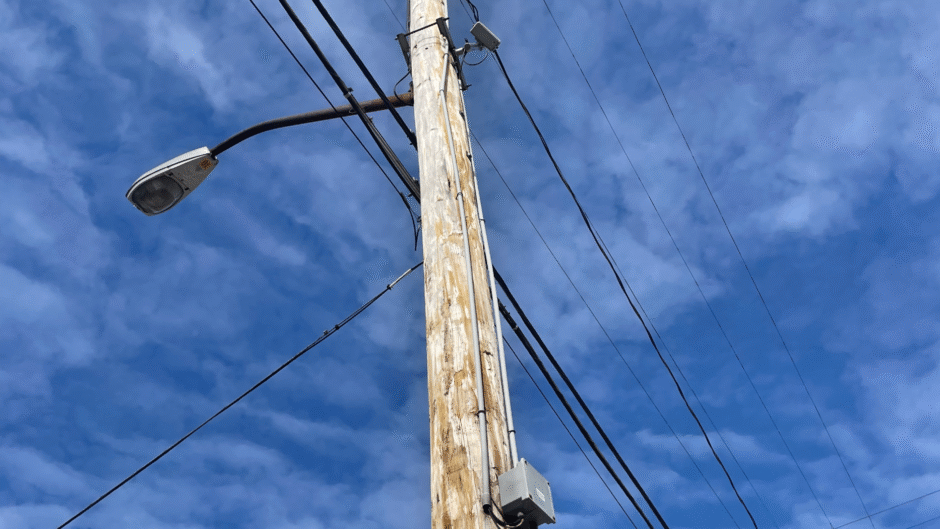

In Pittsburgh, ShotSpotter has been deployed in every Black neighborhood. As the American Civil Liberties Union pointed out in a 2021 report, this creates a situation where “the police will detect more incidents (real or false) in places where the sensors are located. That can distort gunfire statistics and create a circular statistical justification for over-policing in communities of color.”

The risk of ShotSpotter misclassifying loud sounds is compounded by the risk of the loss of life in police-based violence—to which Pittsburgh is no stranger.

Furthermore, as a for-profit company, SoundThinking has an incentive to collaborate with its law enforcement clients. This creates an environment ripe for other abuses and lack of accountability.

This was the case with 65-year-old Michael Williams, who was wrongfully charged with murder after Chicago police asked a ShotSpotter analyst to move the location of an alert to match the crime scene. Though the charges were dropped, Mr. Williams spent 11 months in jail and contracted COVID-19 twice during that time.

In 2016, Silvon Simmons was shot at by a Rochester, NY, police officer in a case of mistaken identity. The officer claimed that Mr. Simmons shot at him instead. The trial against Mr. Simmons revolved around ShotSpotter alerts as evidence, which ShotSpotter analysts reclassified at the requests of the police department.

In 2020, Pittsburgh repealed its predictive policing following calls by Black activists to end the surveillance of Black people. In passing legislation regulating the use of predictive policing and facial recognition by the police, Mr. O’Connor—who was District 5’s city council representative at the time—spoke to the technology’s role in perpetuating bias.

“We have seen how this hurts people of color and people in low-income areas,” he told Pittsburgh CityPaper. Much of the same argument applies to the ShotSpotter system. But Ms. Heisler’s analysis glosses over these problems.

“The [city] controller’s analysis is the latest example of a city searching for any excuse it can find to retain ShotSpotter rather than invest in community programs that address the root causes of gun violence,” Ed Vogel, a researcher with Lucy Parsons Labs, said on Nov. 15. “This is an insult to every Pittsburgh resident whose life has been impacted by gun violence.”

Pittsburgh has multiple projects aiming to prevent gun violence, and Mayor Ed Gainey’s Plan for Peace includes a commitment to a public health model and community partnerships to accomplish this.

Tell City Council what you think

Pittsburgh’s budget hearings are well under way; the one on public safety happened on Nov. 18. The public will have a chance to comment on the budget again at a Dec. 11 public hearing. As of this writing, no date has been set for the council’s vote on renewing ShotSpotter’s contract.

Recent Comments