Watch this video to discover a hidden Pittsburgh gem, The Run—and learn about two serious threats it faces. Our neighborhood needs flood relief, not a new roadway running through it and the neighboring public park. 8-10 million roadway dollars are better spent on infrastructure needs left unaddressed for decades in Pittsburgh neighborhoods. Read the alternative plan and sign the petition!

4MR stormwater project update raises transparency questions

Pittsburgh Water mailed a letter dated Jan. 28 to residents of The Run. It was signed by chief engineering officer Rachael Beam. It assured residents that Pittsburgh Water has not forgotten them. This was Pittsburgh Water’s first formal communication with residents since canceling the project designed to address dangerous flooding in their neighborhood.

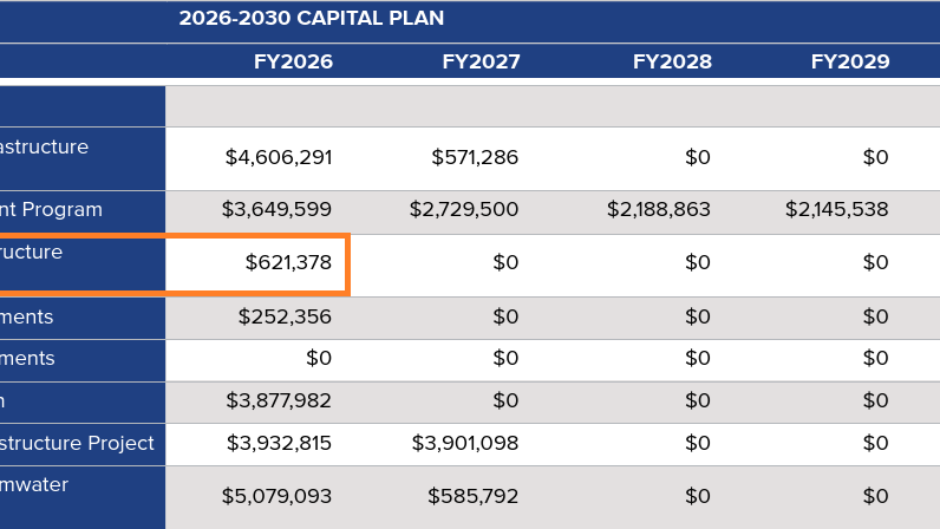

The big news: Pittsburgh Water (also known as PWSA) will continue gathering data from flow monitors installed last year. The authority’s 2026-2030 Capital Improvement Plan includes $621,378 for this. The plan is for Pittsburgh Water to update data it collected in 2019. It will then analyze the effects of work like 2022 repairs to the M-29 outfall pipe into the Monongahela River.

The letter made repeated mentions of seeking “alternative” strategies for flood relief. It did not state outright that Pittsburgh Water has abandoned its $8.7 million design for the Four Mile Run stormwater project. But it seems implied.

Watching and waiting

The project billed as a solution to the Run’s longtime flooding received $41 million in 2017. The Mon-Oakland Connector shuttle road planned for the same location was canceled in 2022. After that, Pittsburgh Water removed the green infrastructure part of the plan. Now it would include only “gray” infrastructure—pipes under the neighborhood itself. The authority reaffirmed its commitment to the project, but quietly eliminated funding in late 2024.

Ms. Beam’s Jan. 28 letter cites “limited capital dollars and the need to prioritize regulatory-driven projects” as the reasons for defunding the project.

“While the Four Mile Run project remains on hold, we continue to explore alternatives, engage with partners, and identify potential funding opportunities to move forward responsibly,” she added.

District 5 City Councilor Barb Warwick organized Run residents to speak at a press conference and Pittsburgh Water board meeting last May. She said the utility has kept its promise to update her monthly.

“The people in The Run will not be satisfied until the flooding is fixed,” she told us during a Feb. 15 phone call. “Maybe the M-29 [outfall work] is the fix, but we won’t know that until PWSA gathers the data and shows us.”

Priorities for limited funds

The utility’s Capital Improvement Plan contains a Project Prioritization section. This part explains the process of deciding which projects get funded each year. A committee reviews each new project proposal and scores it based on six criteria: Regulatory compliance, quality of service, safety, risk of failure, security and social impact. Each is weighted differently. For instance, regulatory compliance has the highest at 25%. The committee uses these scores to list top projects for the Pittsburgh Water executive team. The executive team makes funding decisions, then the board votes on the budget.

But scores are missing from descriptions of the projects themselves. This makes it hard to know how some projects won out over others.

For example, the Capital Improvement Plan includes more than $5.17 million for “Bus Rapid Transit Stormwater Infrastructure Improvements.” This amount is spread out over the next four years.

We asked Pittsburgh Water for the scores the Bus Rapid Transit project and the Four Mile Run project received. The authority did not provide them before the print deadline.

A larger pattern

In December, reports by Public Source raised concerns over Pittsburgh Water’s transparency. Community engagement has been limited. For over two years, board approvals have been unanimous with little or no public discussion. Meanwhile, the authority has raised rates and begun collecting a stormwater fee in 2022.

“The stormwater fee they collect does not go to stormwater. It just goes into the general fund — which feels very non-transparent,” Ms. Warwick said.

Pittsburgh Water livestreams board meetings and posts recordings online. But Public Source found that “board deliberation happens privately” in committee meetings or executive sessions. This practice violates Pennsylvania’s Sunshine Act.

Public Source reported that District 8 City Councilor Erika Strassburger said she and her fellow Pittsburgh Water board members “could be better about daylighting some of the hard discussions we have internally … I’ll own that, and we should all own that.”

One of those “hard discussions” may have involved the Four Mile Run stormwater project. Board members never mentioned it in public budget discussions in the months leading up to defunding it.

Attempts at building trust

Ms. Warwick said Pittsburgh Water has consulted with her on how to approach Run residents. The authority wanted to hold another public meeting because they had told residents they would. Ms. Warwick recommended sending the letter instead.

“Until they have results to share with us,” she said of the data monitoring, “I don’t see much point in dragging residents out to a public meeting.”

She praised the Mon Water Project for its advocacy for The Run and the entire watershed. The nonprofit is also advocating for funding to fix Panther Hollow Lake.

“That would be a huge win not just for flood mitigation, but also for preservation of a historic community asset,” she said.

Peer into the depths

View Pittsburgh Water’s 2026-2030 Capital Improvement Plan at tinyurl.com/pgh-water-capital-plan.

Learn more about flood relief projects Mon Water Project has proposed in and around The Run at monwaterproject.org/initiatives/talk-tour-legislative-2025.

Take a deep dive into the history of the stormwater project at junctioncoalition.org/tag/pwsa.

This article originally appeared in The Homepage.

Hazelwood riverfront rezoning conversation continues: Companies seek trust, residents seek relief

Pittsburgh’s City Planning Commission voted 4-2 on Nov. 18 to approve rezoning land along Hazelwood’s riverfront. But first, the two dissenting commissioners expressed concerns.

Commissioner Steve Mazza worried the railroads would follow through on threats to sue over the rezoning. Chair LaShawn Burton-Falk said she felt uncomfortable moving forward. She could not be sure there was peace between the industrial facilities and nearby residents.

A rail yard, a recycling facility and a salt depot currently sit on Hazelwood’s riverfront. Since the new zoning designation would not remove them, it would not solve residents’ problems.

“If there’s acute trauma perceived and that acute trauma will not disappear, then what?” Ms. Burton-Falk remarked.

The legislation introduced by District 5 Councilor Barb Warwick will now move to City Council.

Ms. Warwick agreed that building trust is part of the work to be done. She has been in discussions between community groups and facility representatives. She took a tour of Republic Services’ plant. But, she emphasized, “Trust doesn’t protect this community from future harm.”

Life next to heavy industry

Smelly garbage. Rats the size of cats. Dust and lighting so intense that the windows must stay closed even at the height of summer. Loud noise and exhaust from trucks at 4:30 a.m.

More than a dozen Hazelwoodians attended the Nov. 18 Planning Commission meeting. They spoke about these conditions in the neighborhood’s Scotch Bottom section. It lies between the railroad tracks and the Monongahela River.

Scotch Bottom residents said owners of the industrial properties made matters worse by ignoring them.

Catherine Phillips had to seek out a rail yard manager because an employee took to parking his truck by the fence in front of her house. He often left it idling all night. She said she and her neighbors were not told about the salt depot or the recycling plant before those businesses moved in.

“Now they want to bring more trash in,” Ms. Phillips added. She was referring to a pending permit that would allow the recycling plant to also handle waste. “For people who live closer than me, this is a disgrace. This is telling us that we are not worth anything.”

“People need jobs, but you’ve got to have respect for the neighbors,” said her neighbor Bernie Moon. “You took Langhorn Street. Langhorn Street is 400 feet long. There was trees all the way down it. Four years ago, the railroad came in and tore them all down. And what did they do to block the noise? Put a fence up. That’s it. Nobody gets a permit; nobody lets anybody know what they’re doing. They just do what they want to do.”

Tiffany Taulton also lives in Hazelwood. She helped start an air quality monitoring network there when she worked for Hazelwood Initiative Inc. She said on Dec. 10 that she used to walk along Langhorn Street. It was a shady, lower-traffic alternative to Second Avenue. Since the trees were removed, she no longer takes that route.

Ms. Taulton said the environmental organization Local Governments for Sustainability (also known as ICLEI USA) has identified that location as a high-risk area for extreme heat and flooding.

Valerie Testa also lives in Hazelwood. She manages community gardens for Hazelwood Initiative Inc., including one in Scotch Bottom.

“People say, ‘If you don’t like it, move.’ That’s not reality,” she said on Dec. 3. “We shouldn’t have to buy our way into a healthy environment.”

“We don’t tend to [get involved in] legislation, but quite a few residents were interested in air quality,” said Lauren Coursey, Hazelwood Initiative Inc.’s director of sustainability and engagement, on Dec. 9.

She has been hearing from residents about health problems that may come from the heavy industry near their homes.

Improving air quality is listed as a top priority in the Greater Hazelwood Neighborhood Plan adopted in 2019.

The permit that started it all

Republic Services took over the recycling plant at 50 Vespucius St. last February. According to the plant’s general manager, Lori Kolczynski, the permit to handle waste was one of many they set out to transfer from the previous owner. Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection granted the permit in 2023.

On Nov. 18, Ms. Warwick said the previous owner never informed residents about adding a waste transfer station. Neighbors only found out about the permit when Republic Services applied to have it transferred. But this was not because of outreach by Republic Services. Calls from concerned residents prompted Ms. Warwick to look into the issue. Then she proposed the rezoning legislation.

City rezoning and state permitting processes are separate. The outcome of Republic Services’ permit application may be decided before Ms. Warwick’s legislation is voted on. The state Department of Environmental Protection website lists the waste transfer station permit as pending technical review since June 23, 2025. The target date for a decision is Jan. 14.

Ms. Kolczynski said Republic Services has no immediate plans to add the waste transfer station if it gets the permit. So far, the Phoenix, Arizona-based company has focused on cleanup. In her presentation to the planning commission, Ms. Kolczynski acknowledged numerous neighborhood complaints about the plant under its previous owners.

“Nothing will be brought into this facility without community input and making sure you guys are comfortable with the way that things are being operated,” she said.

Ms. Kolczynski joined the Greater Hazelwood Community Collaborative and said she has been attending meetings.

Open invitations

During a Dec. 11 phone call, Ms. Kolczynski shared details of work Republic Services has done on the plant.

“Cleaning up the interior allowed us to move more material that was being stored outside into the building,” she said.

They enclosed the facility’s glass crusher so less noise escapes. And they boosted rodent control by setting out and maintaining traps more often. She added that because the facility is so close to the river, “It’s going to be an ongoing fight.”

Another improvement was installing doors on two sides of the building. This cut down on wind that blows material and odors off the property.

“I strongly feel this facility doesn’t smell,” Ms. Kolczynski said. The most frustrating part of the Nov. 18 meeting for her was that residents didn’t seem to notice a difference. She invited people to visit the recycling plant and said they had given a lot of tours.

“We want a chance to show who Republic is,” Ms. Kolczynski said of the company’s commitment to fixing what she called “past indiscretions” by previous owners. “We’re asking for the time and opportunity to prove that it’s more than words.”

Ms. Coursey said she recently toured the plant with Hazelwood Initiative Inc. and Ms. Warwick.

“They have enclosed a lot of what used to be wide open. It is a lot cleaner,” Ms. Coursey said. “But in my opinion, that doesn’t change the trucks and the material itself and the noise. I’m not saying anything crazy; that’s just the truth. Heavy industry is not good for a residential neighborhood, especially so close to homes.”

“We can rezone and also talk,” Ms. Coursey added. “We can do both, we will do both. Hazelwood Initiative is always open to talk. Anyone is invited to our community meetings.”

What about Ms. Burton-Falk’s remarks about the need for dialogue between community members and property owners?

“I’m exploring what recourse the city has to remedy complaints about noise, light and rodents,” Ms. Warwick said on Dec. 11. “Once I understand that, I am ready to sit down with the property owners to discuss a community benefits agreement to remedy the damage caused to the neighbors.”

Public can weigh in again

Before City Council discusses and votes on the rezoning legislation, they must hold a public hearing. As of this writing, no date has been set for that hearing. According to Ms. Warwick’s office, it could take place in mid to late January. Keep an eye on upcoming City Council meetings at pittsburghpa.gov/City-Government/City-Council/Clerks-Office/Council-Meeting-Schedule.

This article originally appeared in The Homepage. Photo by Juliet Martinez.

Should Pittsburgh Continue Funding and Using ShotSpotter?

Pittsburgh has spent almost $8.5 million on a gunshot-detection system called ShotSpotter over the past 10 years. The city’s contract with SoundThinking, ShotSpotter’s California-based parent company, is set to expire at the end of 2025.

Supporters claim ShotSpotter allows police to arrive at crime scenes sooner, which leads to more arrests in gun-related crimes and gunshot victims getting help faster. Critics question its effectiveness and raise concerns about mass surveillance in Black neighborhoods and increasing bias in policing.

With Pittsburgh City Council preparing to discuss whether to renew the ShotSpotter contract, we analyzed an August 2025 audit of the system by City Controller Rachael Heisler’s office. Despite the report’s positive tone, a closer look prompted several disturbing questions.

How (and why) is ShotSpotter being compared to 911 emergency services?

Ms. Heisler’s report fails to address whether ShotSpotter has reduced gun violence, instead evaluating the system against 911. The report’s first result is that “ShotSpotter alerts tend to be just as productive as 911 calls.” Considering ShotSpotter’s $1.2 million per year price tag, shouldn’t the results be more solidly favorable compared to a service the city is not paying for?

In Pennsylvania, the 911 system is run by counties and funded with a statewide $1.95 surcharge on monthly phone bills or, for pre-paid phones, at the point of sale.

How often does ShotSpotter cause Pittsburgh police to respond to false alarms?

Ms. Heisler’s report did not include documentation of ShotSpotter’s false alarm rate, but the system has been known to classify fireworks or other loud sounds as gunfire. This increases the likelihood of wasting emergency resources. Pittsburgh’s police scanner logs reveal multiple examples of false alarms from sources including roofing work; gas explosions; and tires, balloons, or plastic soda bottles popping.

Why have 911 calls in Pittsburgh dropped by 50%?

The biggest mystery comes from the report’s assertion that, “Following the deployment of ShotSpotter, 911 calls decreased dramatically, a 50% drop from 2014.” The report does not list decreasing 911 calls as a goal of using ShotSpotter, but it does refer to the decrease as a “result.”

It seems unlikely that the reasons for 911 calls have undergone an equally dramatic decline. So it’s hard to see this finding in a positive light.

One clue lies in the report’s comparison of 911 and ShotSpotter response times. Charts 9 and 10 on page 16 show ShotSpotter significantly outperforming 911 in this area, although ShotSpotter’s response times got longer each year.

A pair of audits released by Ms. Heisler’s office and Allegheny County Controller Corey O’Connor’s office in September pointed out slowing response times for police and emergency medical services. They recommended increased staffing for the county’s 911 call center and improvements to programs that ensure first responders’ well-being.

While Ms. Heisler’s ShotSpotter report suggests the technology is cutting police response times, a study from the University of California Santa Barbara Economics Department concluded that ShotSpotter dispatches take away from the time police have to respond to 911 calls—effectively worsening their response times to calls of distress made by residents.

These are questions that should be answered before Pittsburgh commits to another long and expensive contract for ShotSpotter.

Questionable benefits, documented harms

According to SoundThinking’s website, more than 180 cities have purchased ShotSpotter. While some cities, like Pittsburgh, have stuck with the technology, others canceled their ShotSpotter contracts or chose not to renew them because of cost, a low confirmation of shootings, and a lack of effect on gun violence.

The most pressing concern about ShotSpotter is that it deepens racial bias in policing. In 2024, Chicago ended its relationship with ShotSpotter after years of controversy and high-profile tragedies. In 2021, a 13-year-old boy named Adam Toledo was chased, shot and killed by a Chicago police officer responding to a ShotSpotter alert. A lawsuit filed against the City of Chicago around misuses of ShotSpotter names Danny Ortiz, a 36-year-old father who was arrested and jailed by police who searched him while responding to a ShotSpotter alert.

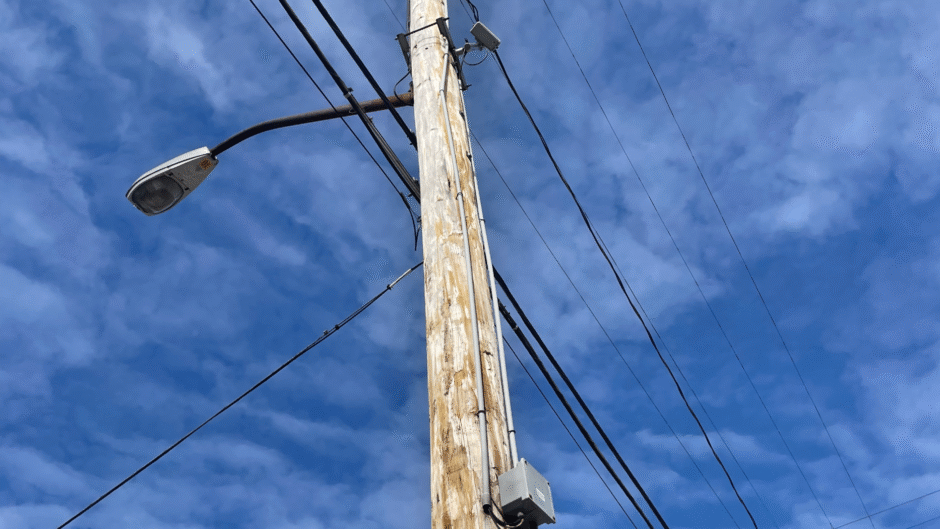

In Pittsburgh, ShotSpotter has been deployed in every Black neighborhood. As the American Civil Liberties Union pointed out in a 2021 report, this creates a situation where “the police will detect more incidents (real or false) in places where the sensors are located. That can distort gunfire statistics and create a circular statistical justification for over-policing in communities of color.”

The risk of ShotSpotter misclassifying loud sounds is compounded by the risk of the loss of life in police-based violence—to which Pittsburgh is no stranger.

Furthermore, as a for-profit company, SoundThinking has an incentive to collaborate with its law enforcement clients. This creates an environment ripe for other abuses and lack of accountability.

This was the case with 65-year-old Michael Williams, who was wrongfully charged with murder after Chicago police asked a ShotSpotter analyst to move the location of an alert to match the crime scene. Though the charges were dropped, Mr. Williams spent 11 months in jail and contracted COVID-19 twice during that time.

In 2016, Silvon Simmons was shot at by a Rochester, NY, police officer in a case of mistaken identity. The officer claimed that Mr. Simmons shot at him instead. The trial against Mr. Simmons revolved around ShotSpotter alerts as evidence, which ShotSpotter analysts reclassified at the requests of the police department.

In 2020, Pittsburgh repealed its predictive policing following calls by Black activists to end the surveillance of Black people. In passing legislation regulating the use of predictive policing and facial recognition by the police, Mr. O’Connor—who was District 5’s city council representative at the time—spoke to the technology’s role in perpetuating bias.

“We have seen how this hurts people of color and people in low-income areas,” he told Pittsburgh CityPaper. Much of the same argument applies to the ShotSpotter system. But Ms. Heisler’s analysis glosses over these problems.

“The [city] controller’s analysis is the latest example of a city searching for any excuse it can find to retain ShotSpotter rather than invest in community programs that address the root causes of gun violence,” Ed Vogel, a researcher with Lucy Parsons Labs, said on Nov. 15. “This is an insult to every Pittsburgh resident whose life has been impacted by gun violence.”

Pittsburgh has multiple projects aiming to prevent gun violence, and Mayor Ed Gainey’s Plan for Peace includes a commitment to a public health model and community partnerships to accomplish this.

Tell City Council what you think

Pittsburgh’s budget hearings are well under way; the one on public safety happened on Nov. 18. The public will have a chance to comment on the budget again at a Dec. 11 public hearing. As of this writing, no date has been set for the council’s vote on renewing ShotSpotter’s contract.

4MR Talk and Tour Revives Flood Relief, Green Infrastructure Conversation

On Oct. 3, about 65 people gathered at the City Reformed Presbyterian Church in The Run to discuss solutions to the neighborhood’s flooding. The discussion has occurred repeatedly over the years, at times in the same basement assembly room when it was owned by International Union of Operating Engineers Local 95.

But this time, the crowd was somewhat different. It included members of 17 nonprofit organizations and community groups; 10 city, county, and state-level governmental agencies; and seven elected officials and their staff.

“We have quite an audience here today — individuals who, I would say, are the decision-makers,” said Mon Water Project founder Annie Quinn, who organized the event. She said she was excited to bring them together with groups pushing for flood relief and green infrastructure.

Not a revolutionary request

Water management problems affect The Run and Pittsburgh as a whole, Ms. Quinn explained. Pittsburgh starts at a disadvantage compared to cities like Philadelphia, which have better soil and less hilly terrain. Like many cities, “We grew systems without growing the infrastructure to support them,” she said.

As a result, every wet-weather event tests the limits of Pittsburgh’s water infrastructure.

“Our sewers overflow in even a tenth of an inch of rain,” Ms. Quinn said. “There is the possibility that The Run will continue to flood, and stormwater issues will be happening right here. But I am not done with my work until the Monongahela River is overflow free as the result of Four Mile Run no longer being the fourth-largest overflow in the city.”

She said Pittsburgh Water (also known as PWSA) has already completed much of the work toward solving this problem.

Ms. Quinn named five solutions she called “project areas”:

1. Separation of sewers in The Run. This means installing a dedicated pipeline for stormwater beneath the neighborhood’s streets. Ms. Quinn described it as “the project that has to happen for anything else to happen.”

2. Restoration of Panther Hollow Lake. The once-popular attraction is less than 4 inches deep, plagued by algae blooms and a recent fish kill. Pittsburgh’s Department of Public Works is applying for permits to do some of the work needed, but a much larger-scale restoration was already designed.

3. Uncovering and restoring buried streams. This would prevent two spring-fed streams from adding about 68 million gallons into the sewer system each year, allowing them to follow their own courses. Ms. Quinn noted that this is similar to work done on Nine Mile Run in Frick Park. “I am not asking for something revolutionary,” she said. “I am asking for a copy-paste of a restoration project that has already occurred and been one of the most successful restoration projects in the country.”

4. Infrastructure in upstream neighborhoods to direct stormwater to storage that could be built under places like Magee Field. Ms. Quinn said ALCOSAN has already identified Magee Field as a good location.

5. Removal of parkway stormwater runoff from the sewer system. PennDOT is planning major construction projects along I-376 Parkway East over the next few years, so now is the time to study how water runoff from the parkway can be diverted.

Pittsburgh Water had planned a $41 million stormwater project in The Run and nearby Schenley Park that included project areas 1–3. After the Mon-Oakland Connector shuttle road planned for the same location was canceled in 2022, Pittsburgh Water scaled back the project to only area 1. Despite reaffirming its commitment to Run residents at that time, Pittsburgh Water eliminated all funding for construction in late 2024.

Renewed determination

After her talk, Ms. Quinn invited Run residents to share their experiences.

Laura Vincent has lived in the neighborhood for 20 years. She remembered the floods starting in about 2006 and occurring every two years until the latest one in 2021. She said she and her husband replaced the hot water heaters, furnaces, washers, and dryers in their home and rental property three or four times. Eventually, they installed backflow valves and rubber membranes that keep both basements dry. But many of their neighbors lack the resources to do so.

“I can’t tell you how many times my husband, at 8:30 in the evening, has run around to all my neighbors to help them re-light pilot lights on their water tanks so at least after they’re done cleaning up their basements they can take a shower,” Ms. Vincent said.

Marianne Holohan, a 13-year resident, talked about raising her two children in The Run. “Part of their story of growing up is, ‘Be careful going outside after it rains because there’s sewage everywhere.’” Ms. Holohan added, “You know, people ride their bikes through this neighborhood constantly. They could also be the victims of the next major flood. It is, in fact, irresponsible to not do any of these projects.”

District 5 City Councilor Barb Warwick thanked Rep. Dan Frankel and Sen. Jay Costa for attending. She emphasized that many of her neighbors in The Run told her after PWSA pulled its funding, “‘They were never going to do that project. They were blowing smoke the entire time.’”

“That is so depressing,” she said. “Annie, just listening to you talk right now — you have galvanized me. These projects were promised to this neighborhood, and they need to get done.”

Working with PennDOT

During the walk through The Run and Junction Hollow, Rep. Frankel spoke with us about state-level solutions.

One obstacle to completing project area 5 is that Pennsylvania’s Department of Transportation (PennDOT) doesn’t perform maintenance beyond the boundaries of a state highway, except as needed to keep the highway structurally sound.

In addition, PennDOT does not pay a stormwater fee. According to Rep. Frankel’s office, government agencies normally don’t have to pay taxes, which the commonwealth says include stormwater fees. But the Pennsylvania Supreme Court is currently considering whether a stormwater management fee is a tax or a fee for service. Pennsylvania does pay fee-for-service charges. The case, Borough of West Chester v. Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education, was argued in 2024; a decision is still pending.

Rep. Frankel co-sponsored legislation introduced by State Reps. Justin Fleming and Dave Madsen. It would require Pennsylvania to pay its fair share of stormwater management fees to local municipalities.

He wrote in an Oct. 10 email, “This is an all-hands-on-deck problem, and I’m glad to help the city of Pittsburgh and the Mon Water Project get every state dollar possible to solve it.”

This article originally appeared in The Homepage.

Water-Focused Event Gives Center Stage to Stormwater, Sewage

Two girls laughed as they scooted through mesh play tunnels representing Pittsburgh’s wastewater system, each racing to throw her squishy poop emojis into the designated blue bin symbolizing a treatment plant.

They were playing the Poop Pipes Game at Pittsburgh’s Got The Runs!, an event hosted by the local nonprofit Mon Water Project on Aug. 27. About 140 people gathered at the Roundhouse on Hazelwood Green for hands-on activities, “lightning talks,” and even a “walk to your poop pipe” hike, all designed to educate residents on Pittsburgh’s unique water issues and encourage them to think about practical solutions.

‘There’s poop in the rivers’

Pittsburgh’s Got The Runs! was part of the city of Pittsburgh’s Summer of Engagement series. Annie Quinn, founder of the Mon Water Project, said she submitted her idea for the community event because city leaders often overlook water-related issues.

“The topic of water is always tied to transportation or sustainability,” she said during a Sept. 3 phone call, adding that the public knows more about those other areas.

With the city seeking public input for its comprehensive plan called Pittsburgh 2050, residents have a chance to identify where attention and funds should go. Ms. Quinn said she wants to help residents understand and explain why water quality and stormwater/wastewater management should be among Pittsburgh’s top priorities. The timing is important for another reason: ALCOSAN is preparing for construction on its Regional Tunnel System, one of the largest infrastructure projects in the region’s history.

Ms. Quinn described most attendees of Pittsburgh’s Got The Runs! as “regular community members” who were not water professionals.

“They knew the rivers were polluted, but now they were hearing why. One woman said to me, ‘So we keep putting a Band-Aid on a system that is failing us? What are we going to do?’ People were empowered, angry and ready to communicate in a way I haven’t seen before,” she said.

Other organizations hosting activities and giving talks included ALCOSAN, the City of Pittsburgh and Pittsburgh City Council, Greenfield Community Association, Hazelwood Initiative Inc, Hazelwood Local, Negley Run Watershed Task Force, One Valley, Pittsburgh Water Collaboratory, Squirrel Hill Urban Coalition, Three Rivers Urban Watershed Council, Three Rivers Waterkeepers, UpstreamPgh and Watersheds of South Pittsburgh.

No news is bad news

Pittsburgh Water (also known as PWSA) presented the final lightning talk of the evening. Holly Bomba, an education and outreach associate with the water authority, explained the utility’s role in delivering clean drinking water and managing storm- and wastewater.

One slide of the presentation showed their stormwater projects on a city map, color-coded by status. Among the seven projects listed as “in planning” was the Four Mile Run stormwater project, which caught the attention of Run residents in the room. Billed as a solution to the neighborhood’s longtime flooding, the project was allotted $41 million in 2017. After the Mon-Oakland Connector shuttle road planned for the same location was canceled in 2022, Pittsburgh Water scaled back the stormwater project to include only “gray” infrastructure — pipes under the neighborhood itself. Despite reaffirming its commitment to their project at the time, Pittsburgh Water eliminated all funding for construction in late 2024.

Pastor Mike Holohan, who lives in The Run, asked Ms. Bomba to explain the project’s “in planning” designation, considering that it was essentially canceled. In her response, Ms. Bomba mentioned that ALCOSAN pulled its grant for the project because green infrastructure work planned in Schenley Park was determined to be not effective enough.

Rebecca Zito, Pittsburgh Water’s senior manager of public affairs, later clarified that ALCOSAN pulled the grant after — not before — Pittsburgh Water removed green infrastructure from the project. She wrote in a Sept. 4 email, “This decision significantly changed the scope, and we would have to resubmit for a new grant to be considered.”

“ALCOSAN evaluated the effectiveness and that’s why they awarded the grant,” commented Ms. Quinn, wondering if ALCOSAN would re-issue the grant if the project were reinstated.

This would only happen if the green infrastructure part of the Four Mile Run project moved forward, since that element is what made the project eligible for ALCOSAN’s GROW grant program. Though Pittsburgh Water has abandoned their $8.7 million design, Ms. Quinn said the Mon Water Project is planning “a focused campaign to install big, climate-resilient projects in Four Mile Run.”

People can get involved by participating in the city’s comprehensive planning process.

“Based on what you learned at this event, identify water as a priority,” she said. “For example, write in ‘Four Mile Run stormwater project.’ We want to sway the comprehensive plan to include details about water and specific solutions.”

P-G editorial admits: No shuttle road, no flood relief

Note: Junction Coalition became aware of a recent P-G editorial that blamed residents of Four Mile Run and allies for Pittsburgh Water’s defunding of flood control efforts in the neighborhood. The editorial labels us “conspiracy theorists,” then concludes that residents should have allowed the community-erasing Mon-Oakland Connector (MOC) project to proceed if they wanted relief from dangerous 75-year floods on their streets. This is exactly the outcome residents have warned of for years.

Junction Coalition stands in solidarity with striking P-G writers. However, we need to correct the record in answer to their attack. The P-G rejected our response, so we are publishing it here. Please share widely!

The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette’s July 13 editorial, “The real reason Four Mile Run is still a flood trap” ignores or mangles basic facts in an effort to rewrite history and preemptively blame the victims of potential catastrophic flooding in The Run. Which, indeed, could happen at any time—but not because our community exposed an attempted land grab by privateers operating behind closed doors.

The Junction Hollow Trail is part of Schenley Park. The P-G blandly labels the proposed MOC route a “corridor” to obscure its true nature: a private road through a public park.

Flood control remained unfunded long after the MOC was announced. After decades of being told Pittsburgh lacked funds to address flooding in our neighborhood, Run residents learned of the roadway from an Aug. 29, 2015, P-G article. The city planned to spend $26 million to connect Oakland university campuses and the ALMONO development in Hazelwood, eliminating The Run’s only community green space. Privately-operated “driverless shuttles” serving only university personnel and students would run every five minutes, 24/7.

The total absence of communication with affected residents about this major project violated Pennsylvania’s Sunshine Act. In addition, the P-G article reported that a newly formed public-private partnership of the URA, CMU, and Pitt filed a $3 million grant application for the project with the Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development (DCED). Their application contained numerous false statements, which the application form states is “punishable by criminal prosecution.” Eventually, the DCED deemed the application “incomplete” and let it expire. Documents received through Right-to-Know requests prove this.

City officials assured residents that the multimodal grant would contain flood-control measures. The claim was quickly proven false, as that specific grant could not be used for anything other than road construction.

Then, in August 2016, a devastating flood caught on camera (and reported by Brian O’Neill) showed our need for flood control in graphic detail. Only then were officials shamed into announcing the $41+ million 4 Mile Run Watershed Improvement Plan the following year, going so far as to call it “the gold standard” for flood mitigation going forward. The catch? Any flood control plan had to be built around the MOC—yet city and Pittsburgh Water representatives rushed to insist these were “two separate projects” happening “in tandem.”

It’s hard to “generate solutions” while being deceived. Several stormwater management professionals offered ideas that were discarded because they did not accommodate the MOC. Pittsburgh Water spent eight years and $8.7 million designing for 10-year floods in a neighborhood that experienced multiple 25- and 75-year floods over the course of one decade.

Only $14 million of the project budget was slated for flood control in the “core area.” According to a 2020 email from senior manager of public affairs Rebecca Zito, “The remaining funding can go towards future projects in the upper portions of the watershed, provide opportunities to collaborate with the universities and other community organizations on future stormwater projects.”

Within six months of Mayor Gainey canceling the MOC in February 2022, Pittsburgh Water removed all green infrastructure elements from their stormwater project. But they continued to promise Run residents, “We are going to do the stormwater project no matter what” until defunding their proposed solution without public discussion at the end of 2024. Pittsburgh Water didn’t inform the public for another few months.

We are going to do the stormwater project no matter what. If the roadway stopped being planned, we would have to amend our permit, which would result in a paperwork review for PA DEP and some timing changes, but we would still do our project. For the stormwater project, the money is committed, the PWSA board has approved it, the design is essentially complete, and we are moving forward with it. We combined the stormwater project with the mobility corridor project because we wanted to limit the number of conflicts from a construction perspective and to make sure the costs were reasonable for our ratepayers and city taxpayers.

—Four Mile Run Stormwater Improvement Project Virtual Community Meeting Minutes (September 15, 2020)

Despite its “zombie status,” the MOC enjoyed a healthy budget well into 2022. The P-G implies that former city councilor Corey O’Connor dealt the MOC’s death blow by removing $4.15 million from its budget in 2020—although the same amount reappeared in the 2022 MOC budget, which totaled about $7 million. By the time Mayor Gainey campaigned against it, the MOC had supposedly become a non-issue. So which is it—did Mayor Gainey doom The Run to languish without a private roadway bulldozed through it, or did he merely glom onto Mr. O’Connor’s heroic pantomime of destroying the MOC?

Opposition to the MOC was never confined to a handful of Run residents. As the P-G admits, the MOC became a defining issue of former mayor Bill Peduto’s second term—and Mr. Peduto became Pittsburgh’s first incumbent mayor to be unseated since 1933. Pittsburgh’s taxpayers and voters have thoroughly vetted and rejected the shuttle road.

No one—including the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PA DEP)—believes the MOC was essential to successful flood control in The Run. In fact, the PA DEP’s technical deficiency letters in response to Pittsburgh Water’s joint permit application contained questions about how including the MOC in the project furthered Pittsburgh Water’s stated goal of managing stormwater in the area.

The MOC hobbled flood control from the beginning, and the stormwater project could be far more effective without it. Dedicated public servants would seize this opportunity to improve on the existing design—if they prioritized residents’ safety above the dreams of universities, foundations, and developers.

The Remaking Cities Institute of CMU stated its intentions for The Run in its 2009 “Remaking Hazelwood” report: “The urban design recommendations proposed in this document extend beyond the boundary of the ALMONO site. The end of Four Mile Run valley, the hillside and Second Avenue are all critical to the overall framework. Some of these areas are publicly-held; others are privately-owned. A map is in the section Development Constraints. The support of the City of Pittsburgh and the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) will be critical to the success of our vision. The ALMONO, LP could try to purchase these sites. Failing that, the URA can support the project by purchasing those properties that are within the scope of the recommendations and making them available for redevelopment in accordance with the proposed strategy.”

The P-G dismisses the idea that moneyed interests would hinge public safety on the MOC—then proceeds to sell this “conspiracy theory” as the solution. In doing so, they echo what we “development constraints” in The Run have warned for years: No shuttle road, no flood relief.

Four Mile Run Residents Talk Next Steps on Defunded Stormwater Project

by Marianne Holohan

Residents of The Run and community partners met at Zano’s Pub House on June 9 to discuss next steps for addressing ongoing flooding problems in the neighborhood. The meeting was called because Pittsburgh Water recently announced that they were pausing the long-awaited flood mitigation project slated to begin in 2025.

Anne Quinn, a Greenfield resident who leads the Mon Water Project, a water advocacy nonprofit, led the June 9 meeting.

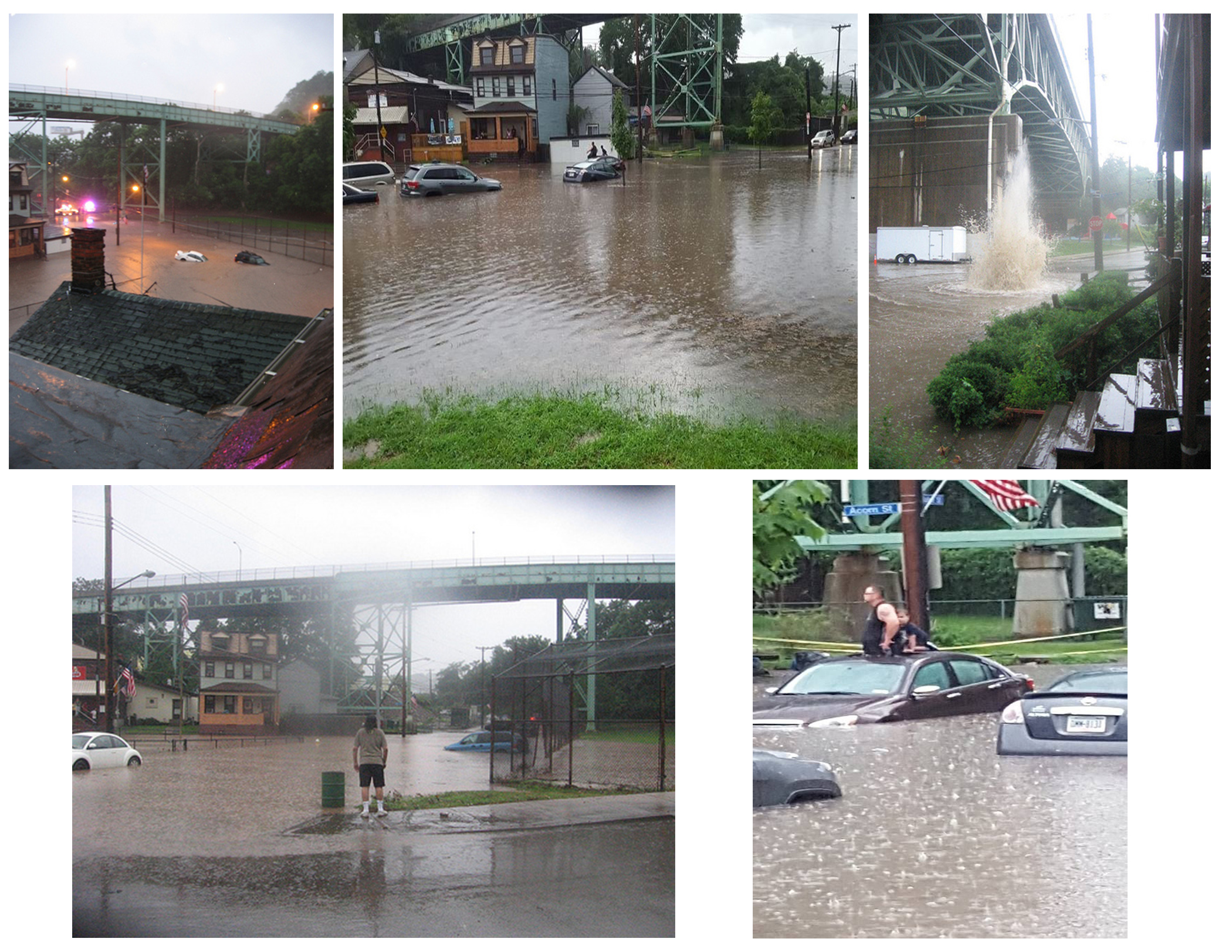

She started with an overview of why The Run continues to flood. She explained that stormwater from uphill communities — Oakland, Greenfield and Squirrel Hill — flows through The Run toward the Mon River. When heavy rainfall occurs, the volume of stormwater overwhelms the system, leading to destructive flash flooding. The Run has two “bowls” where flash flooding occurs: one near the playground on Boundary Street and the other on Saline Street near Big Jim’s restaurant.

Ms. Quinn pointed out that Panther Hollow Lake in lower Schenley Park poses a threat to The Run. The dam intended to contain the lake does not meet legal requirements and is in danger of failure. Should the dam fail, water from the lake would rush into Panther Hollow and The Run, further overwhelming the stormwater system and endangering residents.

The Run has been plagued by destructive flooding for decades. Periodic flash floods block access to the neighborhood and threaten residents’ safety. Pittsburgh Water initiated a flood mitigation project in 2017 that was slated to include the installation of high-capacity piping as well as green infrastructure. In 2022, Pittsburgh Water announced that they had scaled back the project to remove green infrastructure components, and in April 2025, they announced the indefinite pause of the project.

At the June 9 meeting, Ms. Quinn said the installation of bigger pipes is the main solution to The Run’s flooding problem. Building a new stream through Junction Hollow would also allow excess water to flow from Panther Hollow Lake to the Mon River without pooling in The Run. Both of these solutions were included in the initial project design that has now been paused. She also urged residents of uphill communities to mitigate their contributions to stormwater runoff with more green space and permeable surfaces.

After Ms. Quinn spoke, Ziggy Edwards and Ray Gerard of Junction Coalition provided a timeline of flooding issues in The Run and Pittsburgh Water’s troubled mitigation project. Ms. Edwards and Mr. Gerard have reported extensively on these issues. They explained that a flash flood in 2016 left a man and his young son trapped on the roof of their vehicle on Saline Street. Emergency responders had difficulty reaching them because of the rushing flood waters. They also described the lack of transparency from Pittsburgh Water when communicating changes to the project over time.

“The project … suffered from inadequate goals and self-defeating constraints,” Ms. Edwards said on June 14. She said the flood control features were tied to the Mon-Oakland Connector shuttle road project, also called MOC. Pittsburgh Water only admitted as much after Mayor Ed Gainey canceled it in 2022.

“They said they had a model of their project without the MOC but never would show it to us,” she said, adding that only a third of the funding was slated for the core project in Schenley Park and The Run.

The ongoing lack of transparency from Pittsburgh Water has angered longtime residents of The Run who have spent thousands of dollars repairing flood damage. One resident, Laura Vincent, remembered a 2022 community meeting held at the former Operating Engineers Union Hall. At that meeting, she said, a representative of Pittsburgh Water “had the nerve to tell us to be patient.”

Ms. Vincent, who owns two properties in The Run, has been waiting for decades for Pittsburgh Water to address this problem.

Residents of The Run have disproportionately shouldered the financial burden of the flooding. According to Ms. Quinn, residents face rising water utility fees while PennDOT, owner of the Parkway East bridge over Four Mile Run, does not pay any fees to offset the bridge’s substantial contributions to stormwater runoff. This further exacerbates flooding in The Run.

Additionally, residents and other ratepayers have supplied the $8.7 million already spent on the paused flood mitigation project. These funds were used to draw up a full design of the project, including green infrastructure. But Pittsburgh Water has yet to implement it.

District 5 City Councilor Barb Warwick, also a resident of The Run, called a press conference on May 23 during which Run residents and business owners expressed frustration toward Pittsburgh Water for failing to acknowledge the urgency of the project.

As the June 9 meeting came to a close, residents discussed next steps to advocate for the stormwater project. Ms. Quinn encouraged residents to keep pressuring Pittsburgh Water and elected officials. She included Democratic mayoral candidate Corey O’Connor, who indicated at a recent neighborhood meet-and-greet that he considers the stormwater remediation project in The Run a “passion project” of his.

In the meantime, Run residents and business owners are bracing for another flash flood season and hoping their worst fears won’t become reality before Pittsburgh Water finally decides to take action.

Marianne Holohan is a resident of The Run. She also serves on the board of the Greenfield School PTO and is an Allegheny County Democratic Committee rep for the 15th Ward – District 9.

‘Pittsburgh Water broke its promise’

District 5 city councilor demands revival of Four Mile Run stormwater project

City Councilor Barb Warwick and her neighbors in The Run are fighting to convince Pittsburgh Water (formerly PWSA) to reverse its unannounced decision to cut the stormwater project from their capital budget. She spearheaded a May 23 press conference in Four Mile Run Field just before making public comments at Pittsburgh Water’s monthly board meeting.

“Pittsburgh Water broke its promise just like everyone in The Run said they were going to do,” she told reporters, referring to predictions by locals since the utility announced its $40+ million project in 2017.

People from The Run have told The Homepage in recent years that they believed work on flood control would only go through if they dropped their opposition to the proposed Mon-Oakland Connector shuttle road. This road was planned to go through their neighborhood and Schenley Park. Residents and allies throughout Pittsburgh eventually defeated the plan when Mayor Ed Gainey canceled it in 2022. Within six months of the project’s demise, Pittsburgh Water removed all green infrastructure elements from their stormwater project.

Green stormwater infrastructure is a set of passive, nature-based solutions to flooding, according to the environmental group PennFuture. It can include manufactured wetlands, swales and rain gardens that collect and hold rainwater before it enters the sewer system, and porous paving that allows water to soak into the ground.

On May 23, Ms. Warwick recalled the November 2022 public meeting where Pittsburgh Water announced these changes. At that time, the water authority reaffirmed its commitment to completing the project, which had been billed as a solution to The Run’s dangerous flooding issues.

“I stood up in front of my neighbors with PWSA CEO Will Pickering, and I said, ‘Don’t worry, guys; they’re going to fix it,’” she told the crowd.

But sometime in 2024, Pittsburgh Water removed all funding for construction of the project from its capital budget.

This choice was only referenced indirectly during Pittsburgh Water’s November 2024 board meeting. Pittsburgh Water board chair Alex Sciulli said the board had earlier met in executive session and discussed “some updates on some projects.” Soon afterward, board member BJ Leber thanked the finance department for a budget-related education session held that week. She referred to “tough decisions in terms of available resources.”

About 25 residents joined Ms. Warwick at the press conference and shared the urgency they felt about the project.

Dana Provenzano owns Zano’s Pub House on Acorn Street in The Run. She talked about flooding that brought water and sewage into the pub, forcing her to close her doors.

“I have to make it safe and sanitary to serve food. No one compensates me for the money I lose when flooding happens,” she said.

Ms. Provenzano called on Pittsburgh Water board members to put themselves in Run residents’ shoes.

“If it was your business, if it was your family, if it was your friends — would you stand up and say, ‘I will reallocate this money to somebody else’?”

“We’re not just talking about a little water in the basement — we’re talking about life-threatening flash floods that blow off manhole covers and fill the streets and homes with sewer water in a matter of minutes,” said Run resident Cynthia Cerrato. “Every time we get a heavy rain my heart freezes, wondering if this is going to be the big one.”

Residents speak up

Immediately after the press conference, Ms. Warwick and three neighbors carpooled to Pittsburgh Water’s offices where the monthly board meeting was being held.

Pastor Mike Holohan is a Run resident and board member of the Greenfield Community Association. He attended the meeting virtually. He said Pittsburgh Water seemed incredulous that Run residents believed the stormwater and Mon-Oakland Connector, or MOC, were linked. When Pittsburgh Water decided to defund the stormwater project, it did not inform the community association ahead of time.

“Pittsburgh Water may give this or that reason for canceling this project. They may say it has nothing to do with the MOC, but when I stop and look at the narrative arc, it seems pretty clear,” he said. “The wealthy people who make things happen don’t see us as a vital neighborhood, but as an obstacle to overcome. They don’t see what I see — that this is an important place where neighbors are friends and children play, and it’s worth protecting.”

Annie Quinn lives in Greenfield and founded the Mon Water Project to advocate for local watersheds.

“This is an environmental injustice happening right here in our neighborhood. It is a human health emergency. We must demand solutions,” she told reporters. “After 10 years and $8.7 million, no physical solution has been installed.”

In her comments to the board, Ms. Quinn challenged them to not only follow through with the scaled-down project Pittsburgh Water promised after the shuttle road project cancellation, but to bring back the original green infrastructure project that included daylighting Four Mile Run stream.

“I request that you go back to your very own studies — that you produced and paid for,” which recommended connecting the stream to the Monongahela River, she said.

She also asked Pittsburgh Water to work with PennDOT during its planned I-376 project above The Run and not allow PennDOT to add runoff from the overpass to the already overburdened water system below.

Pittsburgh Water responds

Mr. Sciulli responded, “We don’t normally comment on the content of our public speakers, but I think it’s important for the record for me to make a few remarks.”

“The Four Mile Run project should have been a crown jewel for green infrastructure, but it met tons of obstacles and challenges to execute the project,” he said.

Mr. Sciulli enumerated some of those obstacles, including the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection adding constraints by reclassifying Panther Hollow Lake as a high-hazard dam.

“The refusal of the railroad company to allow our construction equipment to cross the rail line, even with the use of their own flagmen at outrageous rates, also caused much of the problem,” he added.

Mr. Sciulli responded to concerns about the Mon-Oakland Connector.

“It wasn’t our project,” he said, but as “good public servants” Pittsburgh Water attempted to save taxpayers money by accommodating it and combining construction costs.

Finally, he said PennDOT would not acknowledge its contribution to flooding in The Run and refused to share costs for the stormwater project.

“While this major investment of this project is on pause until we secure the funding, we haven’t stopped trying to solve the problem,” Mr. Sciulli stressed.

“While this major investment of this project is on pause until we secure the funding, we haven’t stopped trying to solve the problem,” Mr. Sciulli stressed.

That night, former Pittsburgh mayor Bill Peduto responded to media coverage of the press conference in a series of posts to the X social media platform.

“Just a reminder that there was a green stormwater management plan for Four Mile Run. It would have daylighted the streams in Schenley Park, dredged Panther Hollow Lake and ended flooding. Essential Foundation funding ended when the Oakland-Mon Connector project was killed,” the first post read.

Mr. Peduto’s comments contradict Mr. Sciulli’s stated obstacles to the stormwater project and seem to support Run residents’ prediction: No shuttle road, no flood control.

Ms. Quinn held a public meeting in The Run on June 9. About 30 people gathered at Zano’s Pub House to hear an update on the history and status of the stormwater project, as well as discuss next steps to get the funding restored.

Pittsburgh Water Defunds Four Mile Run Stormwater Project

On April 22, District 5 City Councilor Barb Warwick held a post-agenda hearing on Pittsburgh Water’s announced “pause” on the Four Mile Run project and other flood mitigation projects in the city. Representatives of Pittsburgh Water (formerly PWSA) and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers attended and answered questions.

Shifting funds and priorities

Ms. Warwick asked on April 22 why the water authority determined that the project is not as urgent as other flood projects that are still moving forward. At one time more than $40 million was budgeted for it, so the councilor asked what changed.

“It’s really funding,” responded Tony Igwe, Pittsburgh Water’s senior group manager for stormwater.

Mr. Igwe said that about $8.7 million has been spent on the project so far. About half a million went to work on the Bridle Trail in Schenley Park that was supposed to hold water back from The Run. But most of the funds were spent on design and planning. He said construction of the project would have cost about $30 million.

Marc Glowczewski, planning chief for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, said federal environmental infrastructure programs could contribute 75% toward the costs of projects like the one in The Run. Pittsburgh Water would need to submit a letter of intent and then the corps would apply for funding.

Ms. Warwick said the project’s indefinite pause bolsters a longstanding suspicion held by Run residents that they could only get their flooding addressed by accepting the now-shelved Mon-Oakland Connector shuttle road through their neighborhood.

District 8 City Councilor Erika Strassburger is a board member for Pittsburgh Water. She said she has been part of past discussions about the project. “I don’t think it helps to insinuate in any way … that there was somehow a decision that was made to punish the residents of The Run because of an organizing effort,” she said.

Ms. Warwick said some neighbors in The Run must routinely replace their boilers and clean up dead rats in their yards. “So, when I as their council representative explain their disillusion with city government and our city authorities over this project, that is what I’m talking about,” she added.

A ‘long and painful history’

Flooding has plagued The Run for decades, although some older residents have said it was not an issue before construction of the Parkway began in 1949 and uphill neighborhoods like Oakland rapidly developed. As the flooding worsened, Run residents were told repeatedly that Pittsburgh lacked funds to address it.

A 2009 flood, which Pittsburgh Water labels a 75-year event, caused catastrophic damage: Cars floated down the streets in 6 feet of water and sewage, while residents watched the mix breach the first floors of their homes.

Ms. Warwick recalled Pittsburgh Water around 2013 holding small meetings at the homes of Run residents to float ideas for flood mitigation, but a lack of funds meant those discussions went nowhere.

Residents learned of plans for the Mon-Oakland Connector from a 2015 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article. But those plans did not include flood control in The Run. City government and Pittsburgh Water were shamed into securing funds for the Four Mile Run stormwater project after media coverage of a harrowing 2016 flood showed emergency responders rescuing a father and son trapped on top of their car.

The stormwater project was billed as a solution to the flooding, but only a third of the funding was slated for the “core project” in Schenley Park and The Run.

The rest of the funding was intended for possible future projects in the watershed, green infrastructure improvements and partnerships with the universities and nonprofits, according to a 2020 email from Pittsburgh Water’s senior manager of public affairs, Rebecca Zito.

Documents obtained through Right-to-Know requests showed that the current chairman of Pittsburgh Water’s board of directors, Alex Sciulli, preferred a more drastic solution. Going back to at least 2019, he advocated for removing residents from flood-prone areas and “changing the flood plain.” In a 2020 email to then-Mayor Bill Peduto’s chief of staff, Dan Gilman, Mr. Sciulli stressed that the “discussion regarding property acquisition” may need to go forward despite being unpopular.

Within six months of Mayor Ed Gainey’s February 2022 cancellation of the connector project, Pittsburgh Water removed all green infrastructure elements from the Four Mile Run stormwater project. After a November 2022 public meeting announcing the project’s “new direction,” it stagnated. Sometime in 2024, Ms. Warwick said, Pittsburgh Water decided to remove all funding for project construction.

“Given the long and painful history of this flood mitigation project for residents in Four Mile Run, I am beyond disappointed in the decision by Pittsburgh Water to indefinitely postpone this work with no prior notification to me or the community,” she said on May 17.

Residents left treading water

Dana Provenzano has seen her share of flooding. She has owned and operated Zano’s Pub House on Acorn Street in The Run for 12 years.

“When people around the city get flooding, it’s water. When we get flooding, it’s sewage,” she said on May 18. “It’s a health concern. I can’t open my doors until I know it’s safe to serve people.”

Ms. Provenzano said the flooding has been getting worse.

Mr. Igwe mentioned during the post-agenda hearing that 2022 work on the outfall into the Monongahela River may have helped, but they don’t know for sure. The Run hasn’t gotten weather conditions that cause flooding since 2021.

We asked Annie Quinn, founder of the Mon Water Project, if The Run will flood again. She said on May 19 that the watershed outfall updates have stopped the Monongahela River from backing up.

But the pipes under The Run are still a pinch point. Water from parts of Oakland and Squirrel Hill, plus all of Greenfield, converges there. “That hasn’t changed,” she emphasized.

“So, yes, the right amount of rain in a short enough time could activate that pinch point and cause more flooding,” Ms. Quinn concluded.

Community actions in the pipeline

On May 23, as this article went to print, Ms. Warwick and several Run residents were scheduled to hold a press conference and give testimony at Pittsburgh Water’s monthly board meeting.

Ms. Warwick told us she planned to ask Pittsburgh Water to restore funding to the Four Mile Run stormwater project.

“Pittsburgh Water must do right by The Run and reallocate the funding to find a solution to the life-threatening flooding in their neighborhood,” she said.

This article originally appeared in The Homepage.

Why I’m Voting for Ed Gainey

It comes down to the Mon-Oakland Connector (MOC): a boondoggle dreamed up by some of Pittsburgh’s universities and foundations that would have ruined a popular motor-free trail through Schenley Park and established a foothold for wiping my neighborhood (Four Mile Run) off the map.

Why dwell on a project that was discredited and shelved years ago? If you have to ask, it’s because you forgot how the MOC came to be old news. Two men figure prominently in the story—and both are currently running for mayor in Pittsburgh’s Democratic primary.

During Ed Gainey’s first run, he participated in a Zoom debate with the other mayoral candidates. Some of my Hazelwood neighbors and I got a chance to ask about their position on the MOC. Gainey didn’t seem familiar with the project, but showed interest in how we overcame efforts by MOC boosters to pit our neighborhoods against each other. After the debate, I emailed Gainey’s campaign inviting him “down The Run” to see the situation for himself. His wife Michelle replied and we made arrangements for visits to The Run and Hazelwood.

The first time I met Ed Gainey, about 35 of us from both neighborhoods walked with him from Four Mile Run Field into Junction Hollow and back. He asked questions, listened to our answers, and seemed genuinely concerned about our community’s problems. Before any of us mentioned hazardous conditions around the railroad trestle, Gainey noticed and inquired about piles of railroad spikes on the trail where they land after flying off the tracks.

We talked about destructive flooding in The Run and how it’s worsened over decades as uphill neighborhoods—including Oakland university campuses—develop rapidly and tax the sewer system. When Run residents learned of plans for the MOC from a 2015 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article, those plans did not include flood control. Our city government and Pittsburgh Water were shamed into their Four Mile Run stormwater project only after media coverage of a harrowing 2016 flash flood—in which emergency responders had to rescue a father and son trapped on top of their car.

Ed Gainey made no big promises on his first visit to The Run, but soon adopted our cause as part of his campaign. Canceling the MOC was among the first actions he took in office.

Gainey’s challenger, County Controller Corey O’Connor, was our District 5 city council representative throughout our six-and-a-half year fight against the MOC. He watched my neighbors and me show up in force at public meetings, organize marches and press conferences, and file Right to Know requests. In conversations with Run residents he acted as though his hands were tied, the road a foregone conclusion. He was evasive at best when it came to answering our questions and providing information about the MOC. He flat-out lied to us on several occasions.

Corey O’Connor was having completely different conversations with some Hazelwood residents, asking or even pressuring them to publicly support the MOC. In 2021 he played a shell game with the project’s funding, crowing about having moved $4.15 million to different projects in other communities. Mysteriously, $4 million for the MOC reappeared in the 2022 budget before Ed Gainey canceled it. This stunt only showed that O’Connor could have chosen to defund the MOC at any time.

But I’m not writing this because of the status quo. Everyone knows about public officials who bend over backwards to represent the donor class. So many people told me and my neighbors, “You’ll never stop the road; there’s too much money behind it.” I’m writing this because Ed Gainey came to our neighborhood, listened to our issues, and made good on his promise to address them. That never happens!

Bucking the status quo has a cost. Ed Gainey canceling the MOC surely isn’t the sole reason for Pittsburgh’s money-starved news outlets cranking out hit piece after hit piece from the moment he took office. But it surely enraged the universities and Almono Partners when he rescinded their long-coveted private driveway. Although politicians are not known for being above reproach, I’ve never seen a local one criticized with such heavy bias.

By contrast, Corey MOConnor’s campaign has been showered with funds and fawning attention by the very same players who stood to gain from the scrapped shuttle road. I don’t believe it’s a coincidence that he chose Hazelwood Green as the place to announce his run for mayor.

The MOC may be dead and buried, but it’s still an issue in this election. It stands for sharp differences between these two candidates—in their approach to managing Pittsburgh’s resources and in their ethics. And the consequences are still playing out. After the MOC’s demise, Pittsburgh Water called off the green infrastructure part of their stormwater project in The Run. This year they announced the entire project has essentially been canceled, the funds moved elsewhere. The Run needs strong advocates—perhaps now more than ever.

Our neighborhood is a snapshot of each candidate’s priorities demonstrated through their actions. Pittsburgh can choose a mayor who returns to business as usual at our expense, or a mayor who actually tries his best to represent us. Your neighborhood’s issues might be different, but they deserve the same attention Ed Gainey has given us.

For me, the choice is as clear as it ever gets. I haven’t forgotten the MOC, and I certainly haven’t forgotten that Ed Gainey showed up for our community.

Recent Comments