Note: Junction Coalition became aware of a recent P-G editorial that blamed residents of Four Mile Run and allies for Pittsburgh Water’s defunding of flood control efforts in the neighborhood. The editorial labels us “conspiracy theorists,” then concludes that residents should have allowed the community-erasing Mon-Oakland Connector (MOC) project to proceed if they wanted relief from dangerous 75-year floods on their streets. This is exactly the outcome residents have warned of for years.

Junction Coalition stands in solidarity with striking P-G writers. However, we need to correct the record in answer to their attack. The P-G rejected our response, so we are publishing it here. Please share widely!

The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette’s July 13 editorial, “The real reason Four Mile Run is still a flood trap” ignores or mangles basic facts in an effort to rewrite history and preemptively blame the victims of potential catastrophic flooding in The Run. Which, indeed, could happen at any time—but not because our community exposed an attempted land grab by privateers operating behind closed doors.

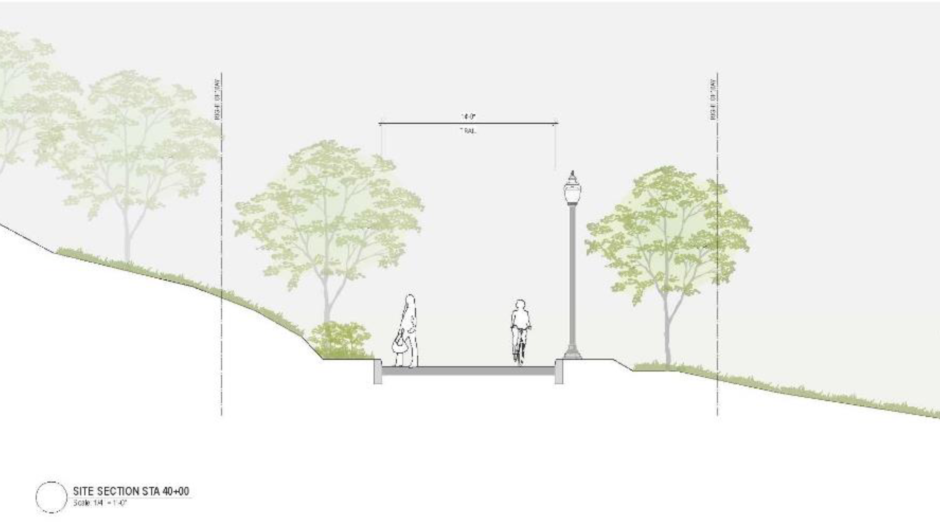

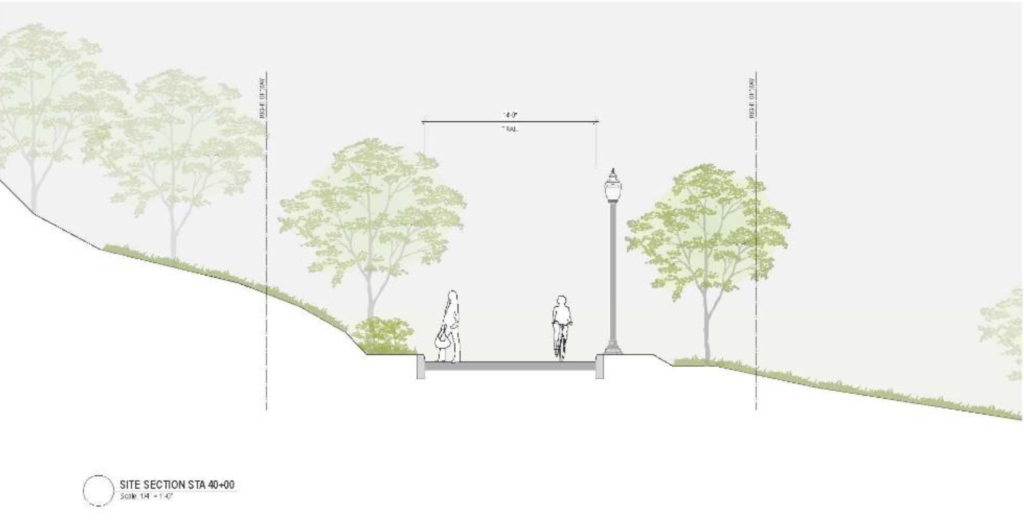

The Junction Hollow Trail is part of Schenley Park. The P-G blandly labels the proposed MOC route a “corridor” to obscure its true nature: a private road through a public park.

Flood control remained unfunded long after the MOC was announced. After decades of being told Pittsburgh lacked funds to address flooding in our neighborhood, Run residents learned of the roadway from an Aug. 29, 2015, P-G article. The city planned to spend $26 million to connect Oakland university campuses and the ALMONO development in Hazelwood, eliminating The Run’s only community green space. Privately-operated “driverless shuttles” serving only university personnel and students would run every five minutes, 24/7.

The total absence of communication with affected residents about this major project violated Pennsylvania’s Sunshine Act. In addition, the P-G article reported that a newly formed public-private partnership of the URA, CMU, and Pitt filed a $3 million grant application for the project with the Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development (DCED). Their application contained numerous false statements, which the application form states is “punishable by criminal prosecution.” Eventually, the DCED deemed the application “incomplete” and let it expire. Documents received through Right-to-Know requests prove this.

City officials assured residents that the multimodal grant would contain flood-control measures. The claim was quickly proven false, as that specific grant could not be used for anything other than road construction.

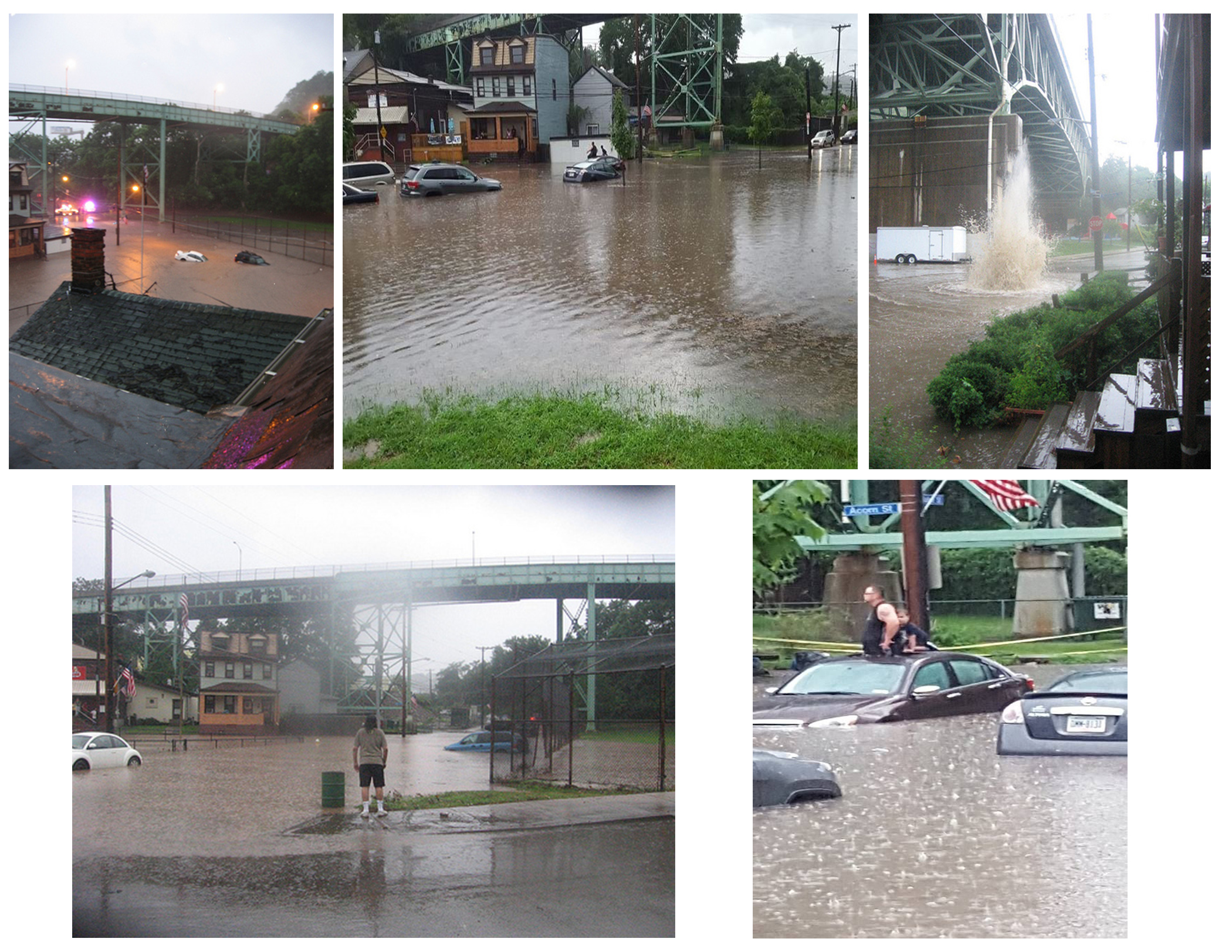

Then, in August 2016, a devastating flood caught on camera (and reported by Brian O’Neill) showed our need for flood control in graphic detail. Only then were officials shamed into announcing the $41+ million 4 Mile Run Watershed Improvement Plan the following year, going so far as to call it “the gold standard” for flood mitigation going forward. The catch? Any flood control plan had to be built around the MOC—yet city and Pittsburgh Water representatives rushed to insist these were “two separate projects” happening “in tandem.”

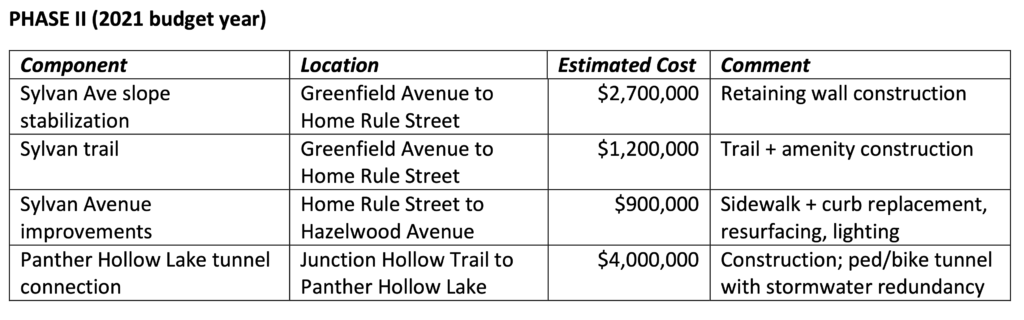

It’s hard to “generate solutions” while being deceived. Several stormwater management professionals offered ideas that were discarded because they did not accommodate the MOC. Pittsburgh Water spent eight years and $8.7 million designing for 10-year floods in a neighborhood that experienced multiple 25- and 75-year floods over the course of one decade.

Only $14 million of the project budget was slated for flood control in the “core area.” According to a 2020 email from senior manager of public affairs Rebecca Zito, “The remaining funding can go towards future projects in the upper portions of the watershed, provide opportunities to collaborate with the universities and other community organizations on future stormwater projects.”

Within six months of Mayor Gainey canceling the MOC in February 2022, Pittsburgh Water removed all green infrastructure elements from their stormwater project. But they continued to promise Run residents, “We are going to do the stormwater project no matter what” until defunding their proposed solution without public discussion at the end of 2024. Pittsburgh Water didn’t inform the public for another few months.

We are going to do the stormwater project no matter what. If the roadway stopped being planned, we would have to amend our permit, which would result in a paperwork review for PA DEP and some timing changes, but we would still do our project. For the stormwater project, the money is committed, the PWSA board has approved it, the design is essentially complete, and we are moving forward with it. We combined the stormwater project with the mobility corridor project because we wanted to limit the number of conflicts from a construction perspective and to make sure the costs were reasonable for our ratepayers and city taxpayers.

—Four Mile Run Stormwater Improvement Project Virtual Community Meeting Minutes (September 15, 2020)

Despite its “zombie status,” the MOC enjoyed a healthy budget well into 2022. The P-G implies that former city councilor Corey O’Connor dealt the MOC’s death blow by removing $4.15 million from its budget in 2020—although the same amount reappeared in the 2022 MOC budget, which totaled about $7 million. By the time Mayor Gainey campaigned against it, the MOC had supposedly become a non-issue. So which is it—did Mayor Gainey doom The Run to languish without a private roadway bulldozed through it, or did he merely glom onto Mr. O’Connor’s heroic pantomime of destroying the MOC?

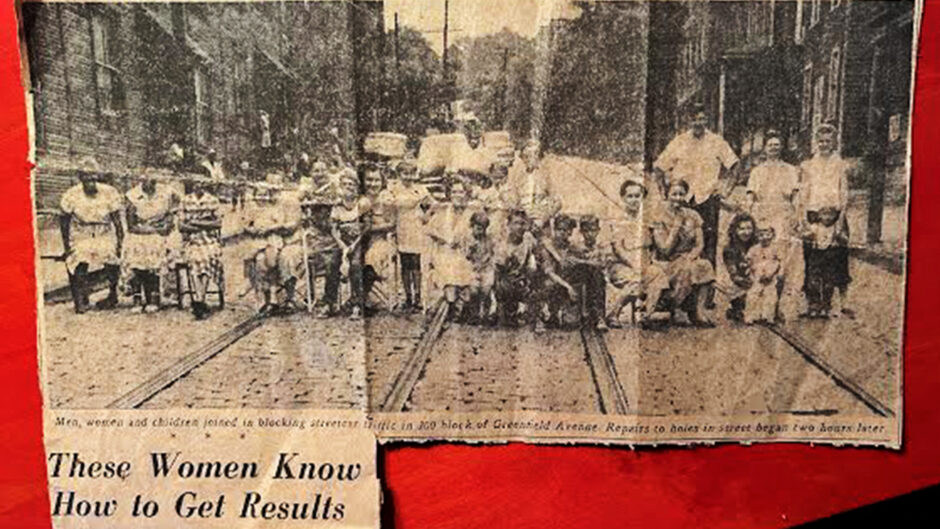

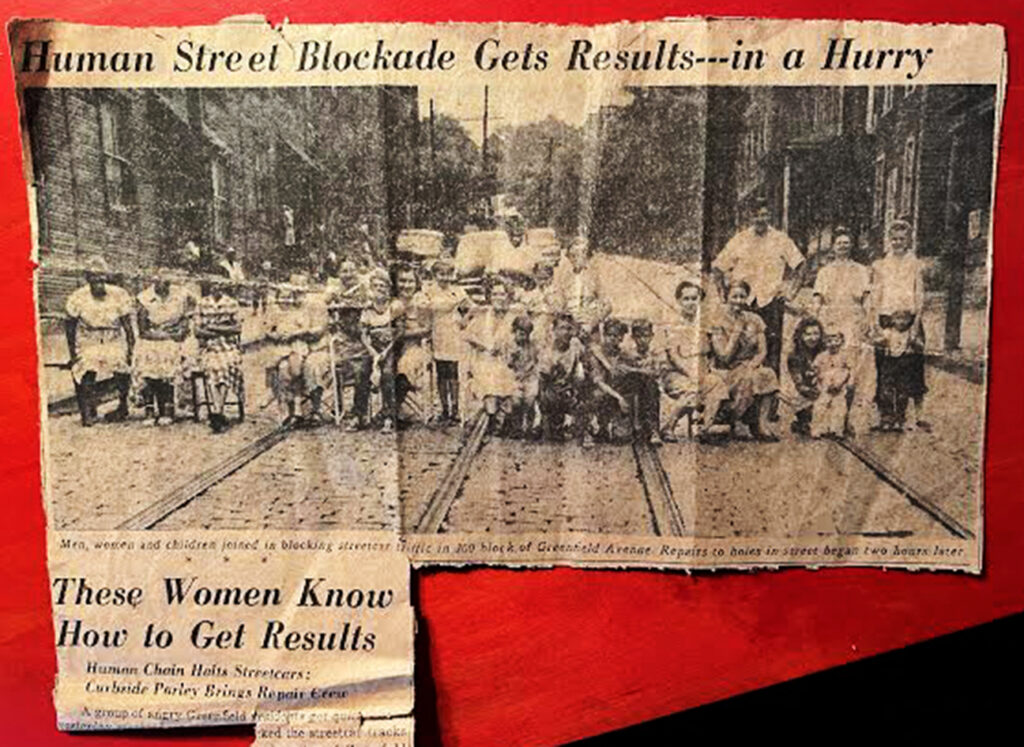

Opposition to the MOC was never confined to a handful of Run residents. As the P-G admits, the MOC became a defining issue of former mayor Bill Peduto’s second term—and Mr. Peduto became Pittsburgh’s first incumbent mayor to be unseated since 1933. Pittsburgh’s taxpayers and voters have thoroughly vetted and rejected the shuttle road.

No one—including the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PA DEP)—believes the MOC was essential to successful flood control in The Run. In fact, the PA DEP’s technical deficiency letters in response to Pittsburgh Water’s joint permit application contained questions about how including the MOC in the project furthered Pittsburgh Water’s stated goal of managing stormwater in the area.

The MOC hobbled flood control from the beginning, and the stormwater project could be far more effective without it. Dedicated public servants would seize this opportunity to improve on the existing design—if they prioritized residents’ safety above the dreams of universities, foundations, and developers.

The Remaking Cities Institute of CMU stated its intentions for The Run in its 2009 “Remaking Hazelwood” report: “The urban design recommendations proposed in this document extend beyond the boundary of the ALMONO site. The end of Four Mile Run valley, the hillside and Second Avenue are all critical to the overall framework. Some of these areas are publicly-held; others are privately-owned. A map is in the section Development Constraints. The support of the City of Pittsburgh and the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) will be critical to the success of our vision. The ALMONO, LP could try to purchase these sites. Failing that, the URA can support the project by purchasing those properties that are within the scope of the recommendations and making them available for redevelopment in accordance with the proposed strategy.”

The P-G dismisses the idea that moneyed interests would hinge public safety on the MOC—then proceeds to sell this “conspiracy theory” as the solution. In doing so, they echo what we “development constraints” in The Run have warned for years: No shuttle road, no flood relief.

Recent Comments