Two girls laughed as they scooted through mesh play tunnels representing Pittsburgh’s wastewater system, each racing to throw her squishy poop emojis into the designated blue bin symbolizing a treatment plant.

They were playing the Poop Pipes Game at Pittsburgh’s Got The Runs!, an event hosted by the local nonprofit Mon Water Project on Aug. 27. About 140 people gathered at the Roundhouse on Hazelwood Green for hands-on activities, “lightning talks,” and even a “walk to your poop pipe” hike, all designed to educate residents on Pittsburgh’s unique water issues and encourage them to think about practical solutions.

‘There’s poop in the rivers’

Pittsburgh’s Got The Runs! was part of the city of Pittsburgh’s Summer of Engagement series. Annie Quinn, founder of the Mon Water Project, said she submitted her idea for the community event because city leaders often overlook water-related issues.

“The topic of water is always tied to transportation or sustainability,” she said during a Sept. 3 phone call, adding that the public knows more about those other areas.

With the city seeking public input for its comprehensive plan called Pittsburgh 2050, residents have a chance to identify where attention and funds should go. Ms. Quinn said she wants to help residents understand and explain why water quality and stormwater/wastewater management should be among Pittsburgh’s top priorities. The timing is important for another reason: ALCOSAN is preparing for construction on its Regional Tunnel System, one of the largest infrastructure projects in the region’s history.

Ms. Quinn described most attendees of Pittsburgh’s Got The Runs! as “regular community members” who were not water professionals.

“They knew the rivers were polluted, but now they were hearing why. One woman said to me, ‘So we keep putting a Band-Aid on a system that is failing us? What are we going to do?’ People were empowered, angry and ready to communicate in a way I haven’t seen before,” she said.

Other organizations hosting activities and giving talks included ALCOSAN, the City of Pittsburgh and Pittsburgh City Council, Greenfield Community Association, Hazelwood Initiative Inc, Hazelwood Local, Negley Run Watershed Task Force, One Valley, Pittsburgh Water Collaboratory, Squirrel Hill Urban Coalition, Three Rivers Urban Watershed Council, Three Rivers Waterkeepers, UpstreamPgh and Watersheds of South Pittsburgh.

No news is bad news

Pittsburgh Water (also known as PWSA) presented the final lightning talk of the evening. Holly Bomba, an education and outreach associate with the water authority, explained the utility’s role in delivering clean drinking water and managing storm- and wastewater.

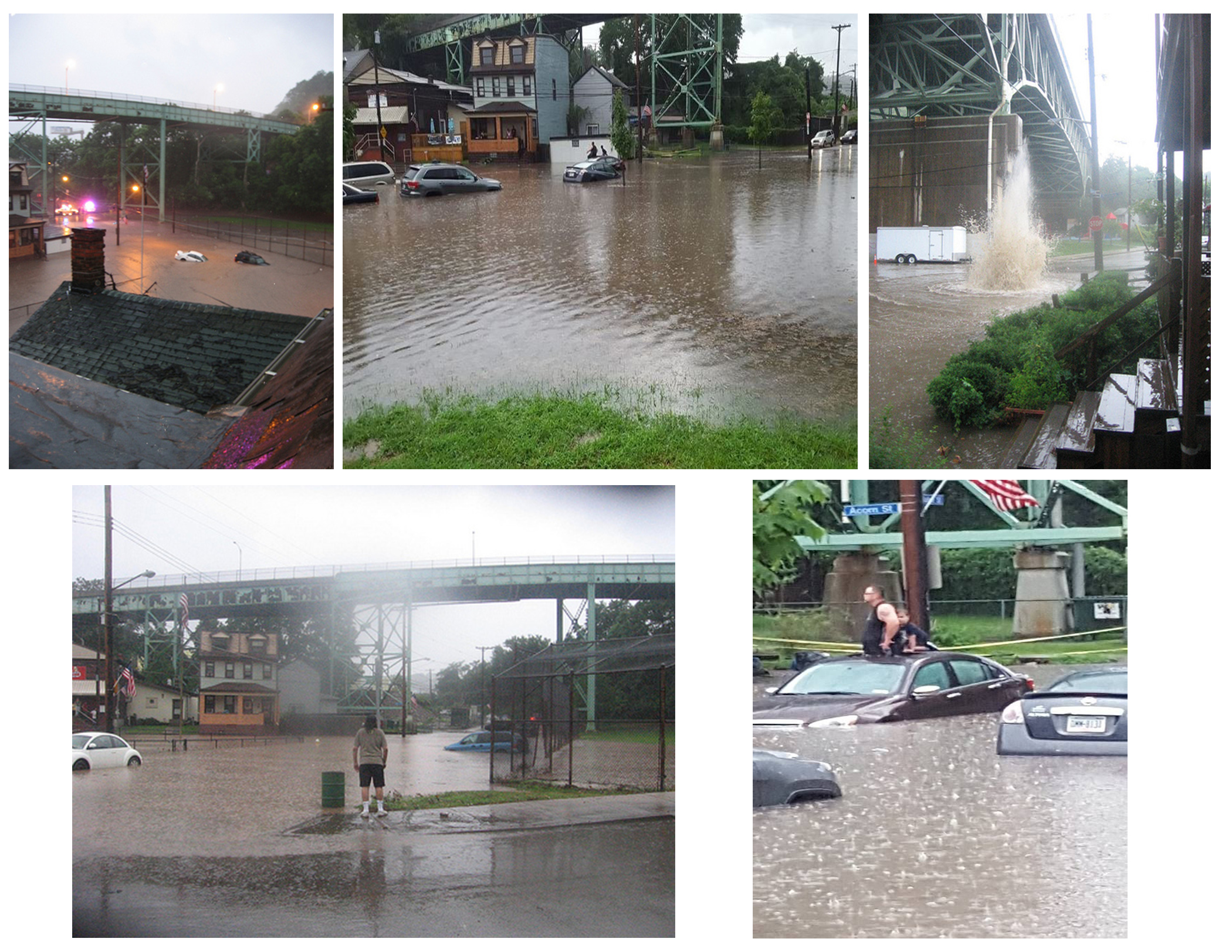

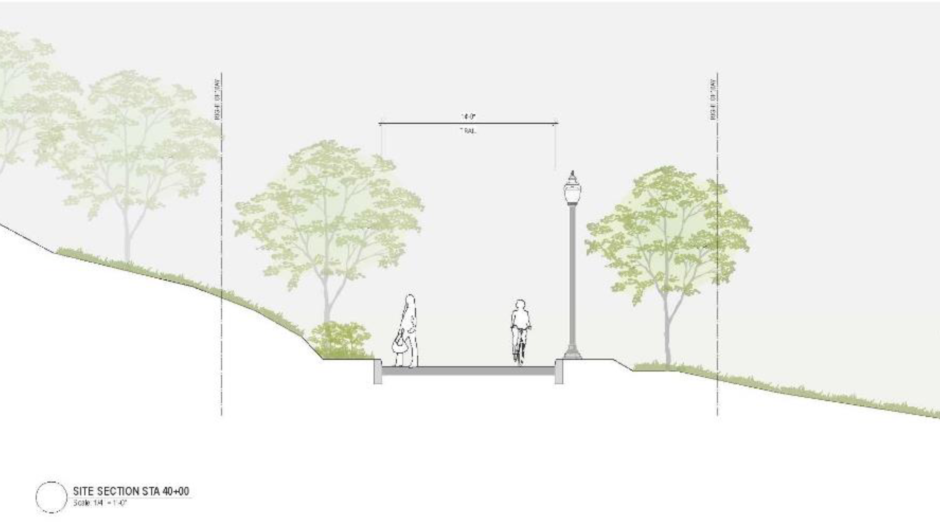

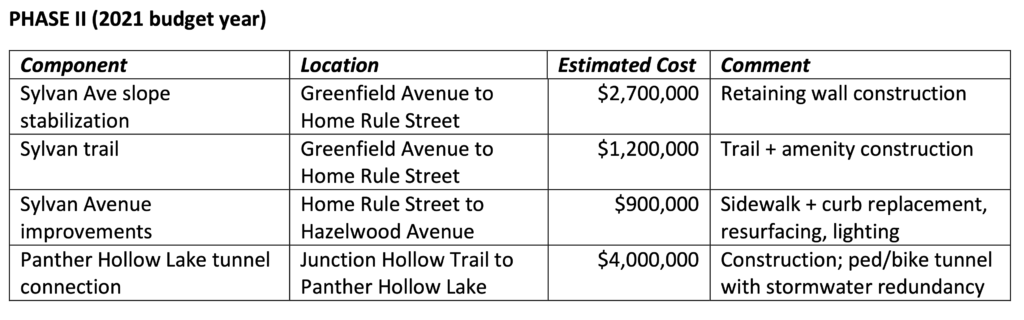

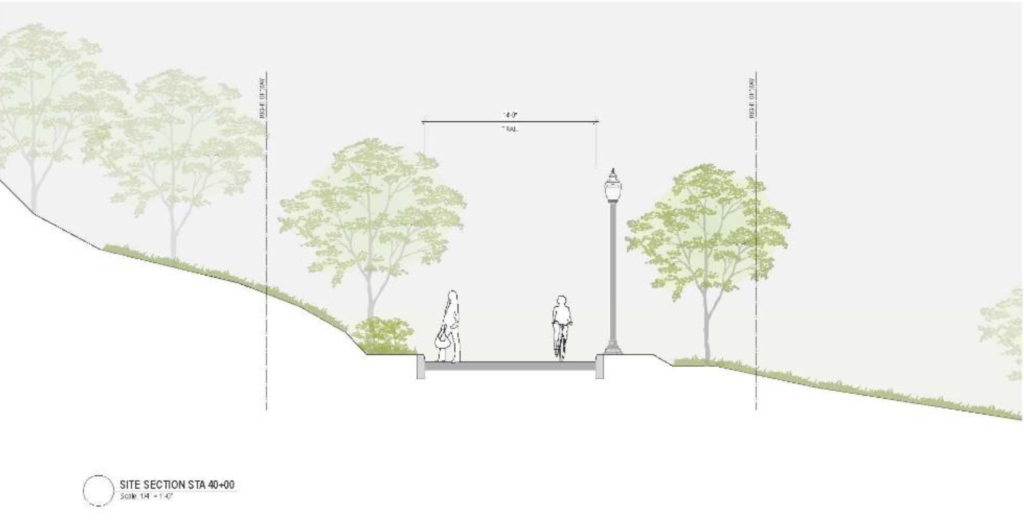

One slide of the presentation showed their stormwater projects on a city map, color-coded by status. Among the seven projects listed as “in planning” was the Four Mile Run stormwater project, which caught the attention of Run residents in the room. Billed as a solution to the neighborhood’s longtime flooding, the project was allotted $41 million in 2017. After the Mon-Oakland Connector shuttle road planned for the same location was canceled in 2022, Pittsburgh Water scaled back the stormwater project to include only “gray” infrastructure — pipes under the neighborhood itself. Despite reaffirming its commitment to their project at the time, Pittsburgh Water eliminated all funding for construction in late 2024.

Pastor Mike Holohan, who lives in The Run, asked Ms. Bomba to explain the project’s “in planning” designation, considering that it was essentially canceled. In her response, Ms. Bomba mentioned that ALCOSAN pulled its grant for the project because green infrastructure work planned in Schenley Park was determined to be not effective enough.

Rebecca Zito, Pittsburgh Water’s senior manager of public affairs, later clarified that ALCOSAN pulled the grant after — not before — Pittsburgh Water removed green infrastructure from the project. She wrote in a Sept. 4 email, “This decision significantly changed the scope, and we would have to resubmit for a new grant to be considered.”

“ALCOSAN evaluated the effectiveness and that’s why they awarded the grant,” commented Ms. Quinn, wondering if ALCOSAN would re-issue the grant if the project were reinstated.

This would only happen if the green infrastructure part of the Four Mile Run project moved forward, since that element is what made the project eligible for ALCOSAN’s GROW grant program. Though Pittsburgh Water has abandoned their $8.7 million design, Ms. Quinn said the Mon Water Project is planning “a focused campaign to install big, climate-resilient projects in Four Mile Run.”

People can get involved by participating in the city’s comprehensive planning process.

“Based on what you learned at this event, identify water as a priority,” she said. “For example, write in ‘Four Mile Run stormwater project.’ We want to sway the comprehensive plan to include details about water and specific solutions.”

Recent Comments