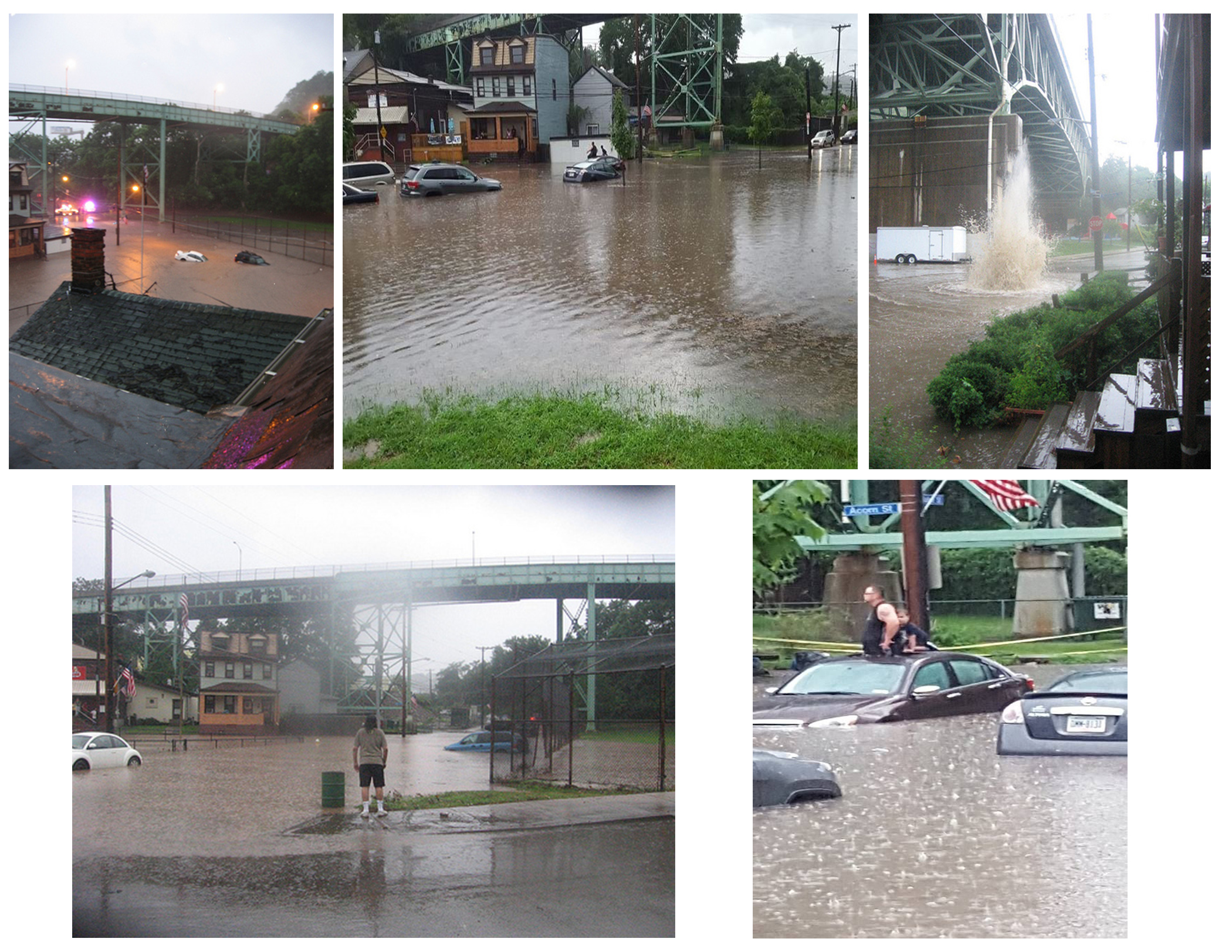

Pittsburgh Water mailed a letter dated Jan. 28 to residents of The Run. It was signed by chief engineering officer Rachael Beam. It assured residents that Pittsburgh Water has not forgotten them. This was Pittsburgh Water’s first formal communication with residents since canceling the project designed to address dangerous flooding in their neighborhood.

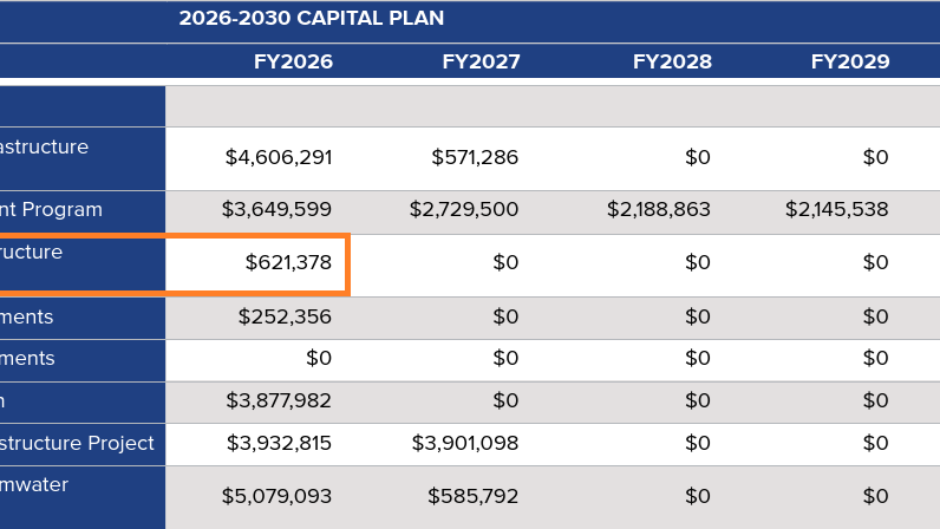

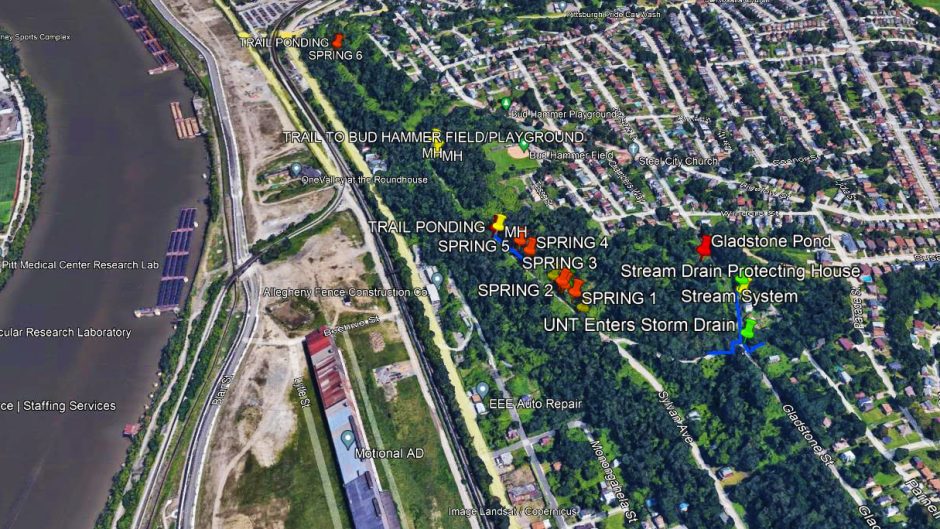

The big news: Pittsburgh Water (also known as PWSA) will continue gathering data from flow monitors installed last year. The authority’s 2026-2030 Capital Improvement Plan includes $621,378 for this. The plan is for Pittsburgh Water to update data it collected in 2019. It will then analyze the effects of work like 2022 repairs to the M-29 outfall pipe into the Monongahela River.

The letter made repeated mentions of seeking “alternative” strategies for flood relief. It did not state outright that Pittsburgh Water has abandoned its $8.7 million design for the Four Mile Run stormwater project. But it seems implied.

Watching and waiting

The project billed as a solution to the Run’s longtime flooding received $41 million in 2017. The Mon-Oakland Connector shuttle road planned for the same location was canceled in 2022. After that, Pittsburgh Water removed the green infrastructure part of the plan. Now it would include only “gray” infrastructure—pipes under the neighborhood itself. The authority reaffirmed its commitment to the project, but quietly eliminated funding in late 2024.

Ms. Beam’s Jan. 28 letter cites “limited capital dollars and the need to prioritize regulatory-driven projects” as the reasons for defunding the project.

“While the Four Mile Run project remains on hold, we continue to explore alternatives, engage with partners, and identify potential funding opportunities to move forward responsibly,” she added.

District 5 City Councilor Barb Warwick organized Run residents to speak at a press conference and Pittsburgh Water board meeting last May. She said the utility has kept its promise to update her monthly.

“The people in The Run will not be satisfied until the flooding is fixed,” she told us during a Feb. 15 phone call. “Maybe the M-29 [outfall work] is the fix, but we won’t know that until PWSA gathers the data and shows us.”

Priorities for limited funds

The utility’s Capital Improvement Plan contains a Project Prioritization section. This part explains the process of deciding which projects get funded each year. A committee reviews each new project proposal and scores it based on six criteria: Regulatory compliance, quality of service, safety, risk of failure, security and social impact. Each is weighted differently. For instance, regulatory compliance has the highest at 25%. The committee uses these scores to list top projects for the Pittsburgh Water executive team. The executive team makes funding decisions, then the board votes on the budget.

But scores are missing from descriptions of the projects themselves. This makes it hard to know how some projects won out over others.

For example, the Capital Improvement Plan includes more than $5.17 million for “Bus Rapid Transit Stormwater Infrastructure Improvements.” This amount is spread out over the next four years.

We asked Pittsburgh Water for the scores the Bus Rapid Transit project and the Four Mile Run project received. The authority did not provide them before the print deadline.

A larger pattern

In December, reports by Public Source raised concerns over Pittsburgh Water’s transparency. Community engagement has been limited. For over two years, board approvals have been unanimous with little or no public discussion. Meanwhile, the authority has raised rates and begun collecting a stormwater fee in 2022.

“The stormwater fee they collect does not go to stormwater. It just goes into the general fund — which feels very non-transparent,” Ms. Warwick said.

Pittsburgh Water livestreams board meetings and posts recordings online. But Public Source found that “board deliberation happens privately” in committee meetings or executive sessions. This practice violates Pennsylvania’s Sunshine Act.

Public Source reported that District 8 City Councilor Erika Strassburger said she and her fellow Pittsburgh Water board members “could be better about daylighting some of the hard discussions we have internally … I’ll own that, and we should all own that.”

One of those “hard discussions” may have involved the Four Mile Run stormwater project. Board members never mentioned it in public budget discussions in the months leading up to defunding it.

Attempts at building trust

Ms. Warwick said Pittsburgh Water has consulted with her on how to approach Run residents. The authority wanted to hold another public meeting because they had told residents they would. Ms. Warwick recommended sending the letter instead.

“Until they have results to share with us,” she said of the data monitoring, “I don’t see much point in dragging residents out to a public meeting.”

She praised the Mon Water Project for its advocacy for The Run and the entire watershed. The nonprofit is also advocating for funding to fix Panther Hollow Lake.

“That would be a huge win not just for flood mitigation, but also for preservation of a historic community asset,” she said.

Peer into the depths

View Pittsburgh Water’s 2026-2030 Capital Improvement Plan at tinyurl.com/pgh-water-capital-plan.

Learn more about flood relief projects Mon Water Project has proposed in and around The Run at monwaterproject.org/initiatives/talk-tour-legislative-2025.

Take a deep dive into the history of the stormwater project at junctioncoalition.org/tag/pwsa.

This article originally appeared in The Homepage.

Recent Comments