On April 22, District 5 City Councilor Barb Warwick held a post-agenda hearing on Pittsburgh Water’s announced “pause” on the Four Mile Run project and other flood mitigation projects in the city. Representatives of Pittsburgh Water (formerly PWSA) and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers attended and answered questions.

Shifting funds and priorities

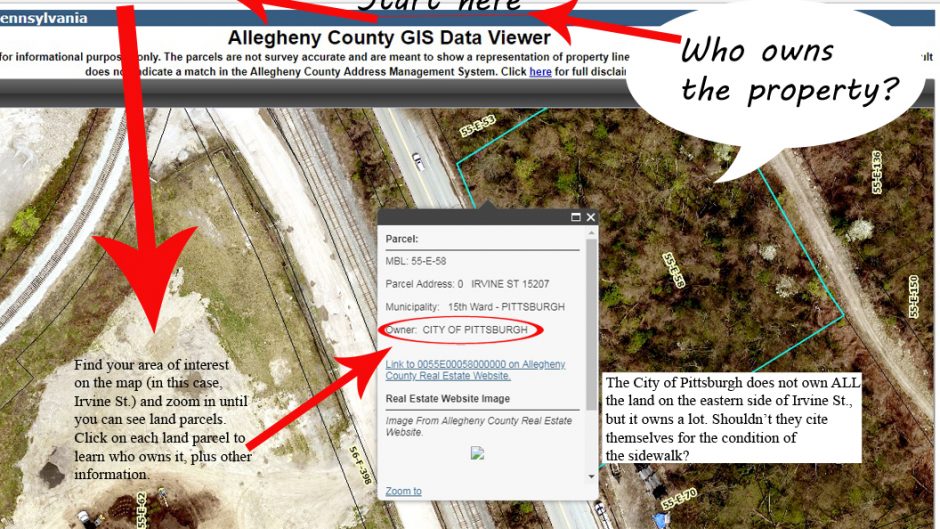

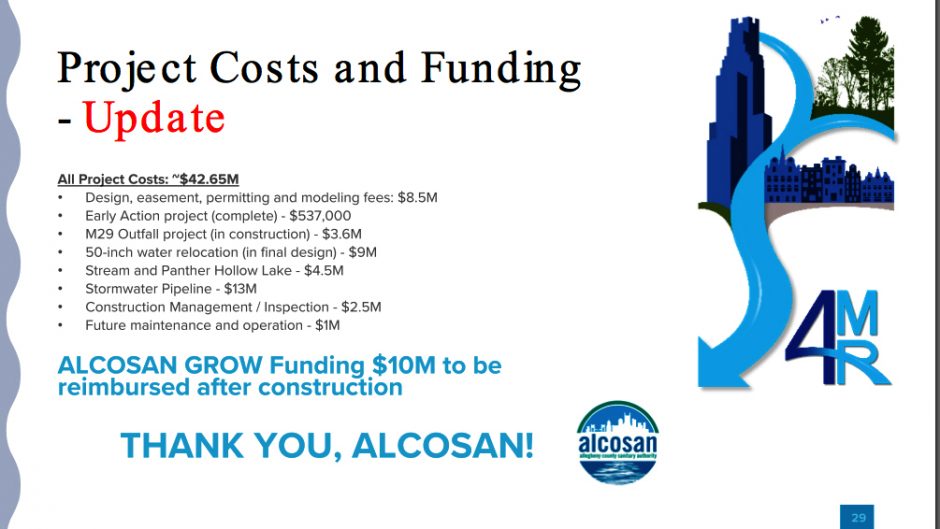

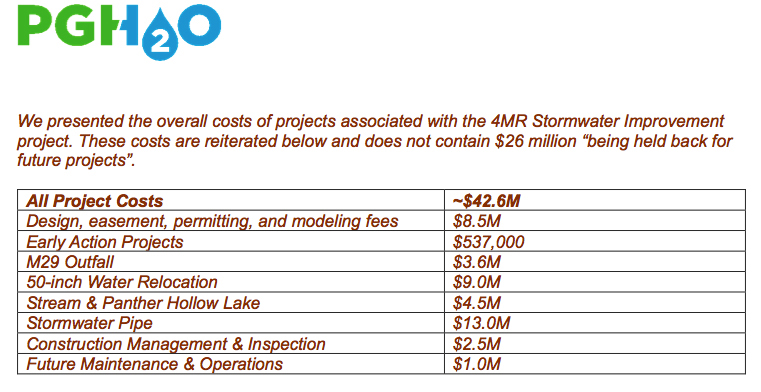

Ms. Warwick asked on April 22 why the water authority determined that the project is not as urgent as other flood projects that are still moving forward. At one time more than $40 million was budgeted for it, so the councilor asked what changed.

“It’s really funding,” responded Tony Igwe, Pittsburgh Water’s senior group manager for stormwater.

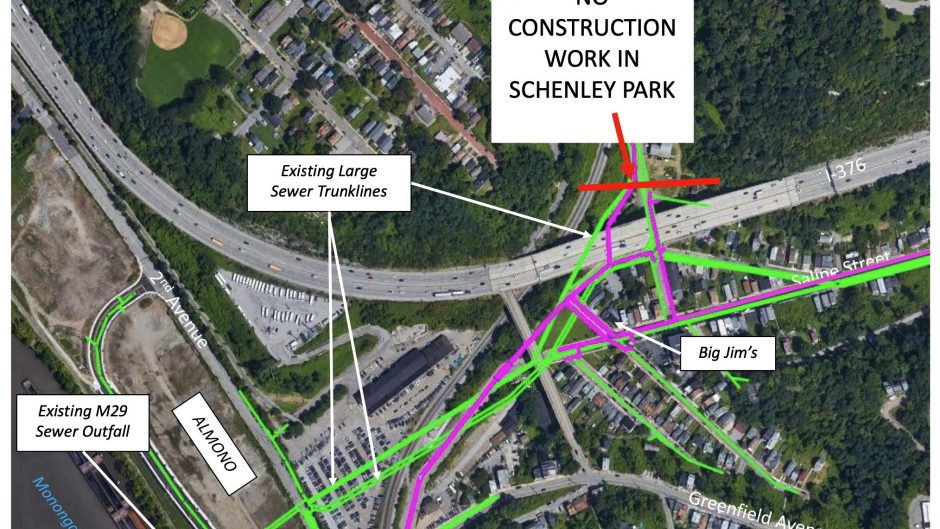

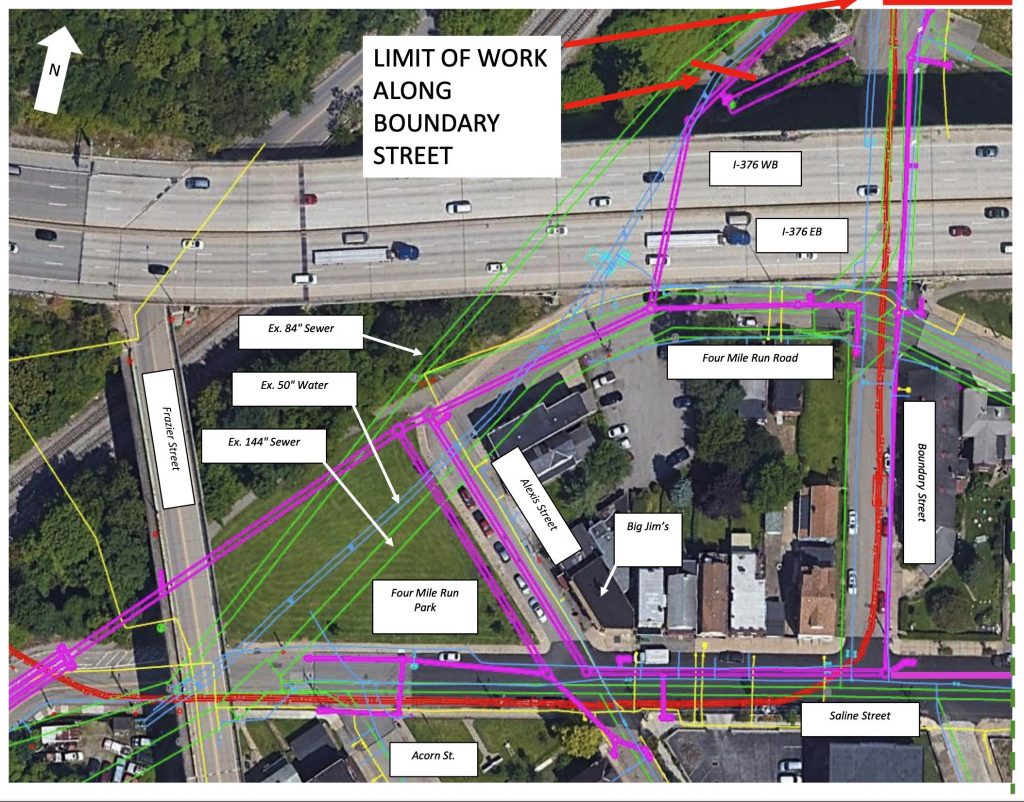

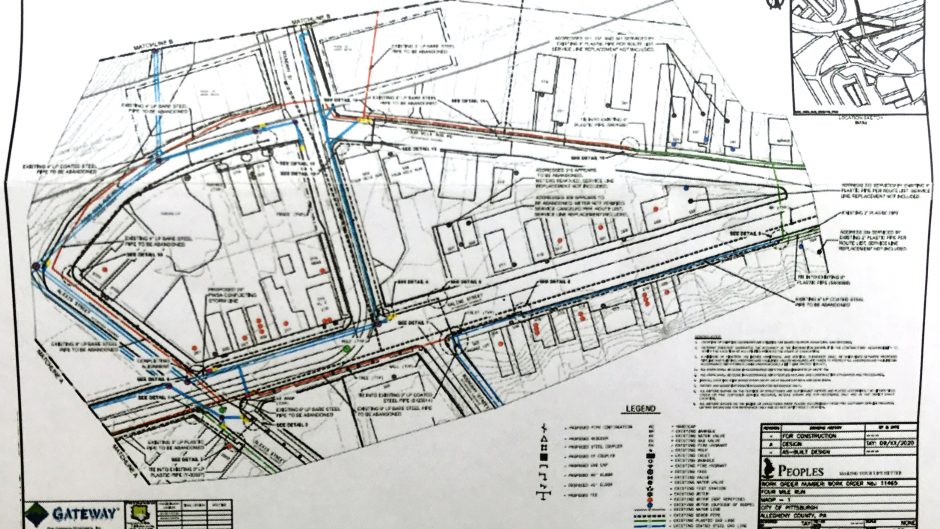

Mr. Igwe said that about $8.7 million has been spent on the project so far. About half a million went to work on the Bridle Trail in Schenley Park that was supposed to hold water back from The Run. But most of the funds were spent on design and planning. He said construction of the project would have cost about $30 million.

Marc Glowczewski, planning chief for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, said federal environmental infrastructure programs could contribute 75% toward the costs of projects like the one in The Run. Pittsburgh Water would need to submit a letter of intent and then the corps would apply for funding.

Ms. Warwick said the project’s indefinite pause bolsters a longstanding suspicion held by Run residents that they could only get their flooding addressed by accepting the now-shelved Mon-Oakland Connector shuttle road through their neighborhood.

District 8 City Councilor Erika Strassburger is a board member for Pittsburgh Water. She said she has been part of past discussions about the project. “I don’t think it helps to insinuate in any way … that there was somehow a decision that was made to punish the residents of The Run because of an organizing effort,” she said.

Ms. Warwick said some neighbors in The Run must routinely replace their boilers and clean up dead rats in their yards. “So, when I as their council representative explain their disillusion with city government and our city authorities over this project, that is what I’m talking about,” she added.

A ‘long and painful history’

Flooding has plagued The Run for decades, although some older residents have said it was not an issue before construction of the Parkway began in 1949 and uphill neighborhoods like Oakland rapidly developed. As the flooding worsened, Run residents were told repeatedly that Pittsburgh lacked funds to address it.

A 2009 flood, which Pittsburgh Water labels a 75-year event, caused catastrophic damage: Cars floated down the streets in 6 feet of water and sewage, while residents watched the mix breach the first floors of their homes.

Ms. Warwick recalled Pittsburgh Water around 2013 holding small meetings at the homes of Run residents to float ideas for flood mitigation, but a lack of funds meant those discussions went nowhere.

Residents learned of plans for the Mon-Oakland Connector from a 2015 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article. But those plans did not include flood control in The Run. City government and Pittsburgh Water were shamed into securing funds for the Four Mile Run stormwater project after media coverage of a harrowing 2016 flood showed emergency responders rescuing a father and son trapped on top of their car.

The stormwater project was billed as a solution to the flooding, but only a third of the funding was slated for the “core project” in Schenley Park and The Run.

The rest of the funding was intended for possible future projects in the watershed, green infrastructure improvements and partnerships with the universities and nonprofits, according to a 2020 email from Pittsburgh Water’s senior manager of public affairs, Rebecca Zito.

Documents obtained through Right-to-Know requests showed that the current chairman of Pittsburgh Water’s board of directors, Alex Sciulli, preferred a more drastic solution. Going back to at least 2019, he advocated for removing residents from flood-prone areas and “changing the flood plain.” In a 2020 email to then-Mayor Bill Peduto’s chief of staff, Dan Gilman, Mr. Sciulli stressed that the “discussion regarding property acquisition” may need to go forward despite being unpopular.

Within six months of Mayor Ed Gainey’s February 2022 cancellation of the connector project, Pittsburgh Water removed all green infrastructure elements from the Four Mile Run stormwater project. After a November 2022 public meeting announcing the project’s “new direction,” it stagnated. Sometime in 2024, Ms. Warwick said, Pittsburgh Water decided to remove all funding for project construction.

“Given the long and painful history of this flood mitigation project for residents in Four Mile Run, I am beyond disappointed in the decision by Pittsburgh Water to indefinitely postpone this work with no prior notification to me or the community,” she said on May 17.

Residents left treading water

Dana Provenzano has seen her share of flooding. She has owned and operated Zano’s Pub House on Acorn Street in The Run for 12 years.

“When people around the city get flooding, it’s water. When we get flooding, it’s sewage,” she said on May 18. “It’s a health concern. I can’t open my doors until I know it’s safe to serve people.”

Ms. Provenzano said the flooding has been getting worse.

Mr. Igwe mentioned during the post-agenda hearing that 2022 work on the outfall into the Monongahela River may have helped, but they don’t know for sure. The Run hasn’t gotten weather conditions that cause flooding since 2021.

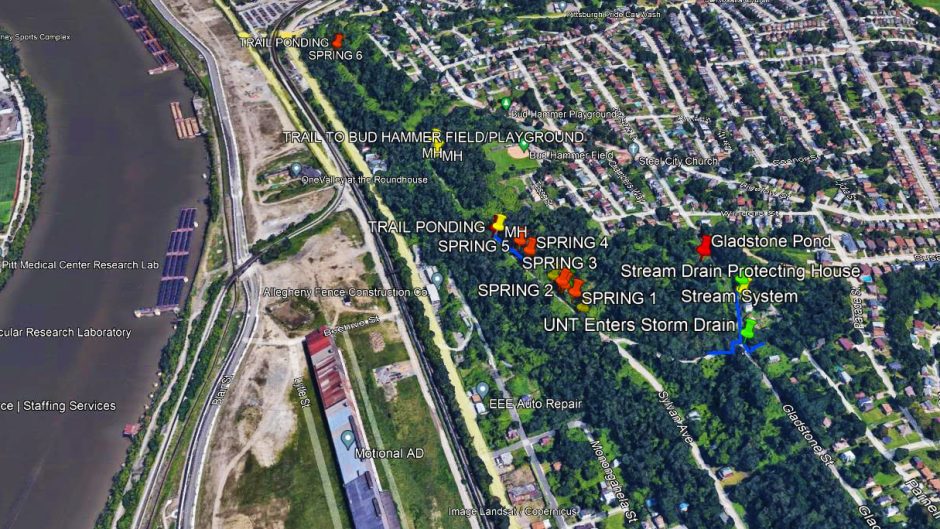

We asked Annie Quinn, founder of the Mon Water Project, if The Run will flood again. She said on May 19 that the watershed outfall updates have stopped the Monongahela River from backing up.

But the pipes under The Run are still a pinch point. Water from parts of Oakland and Squirrel Hill, plus all of Greenfield, converges there. “That hasn’t changed,” she emphasized.

“So, yes, the right amount of rain in a short enough time could activate that pinch point and cause more flooding,” Ms. Quinn concluded.

Community actions in the pipeline

On May 23, as this article went to print, Ms. Warwick and several Run residents were scheduled to hold a press conference and give testimony at Pittsburgh Water’s monthly board meeting.

Ms. Warwick told us she planned to ask Pittsburgh Water to restore funding to the Four Mile Run stormwater project.

“Pittsburgh Water must do right by The Run and reallocate the funding to find a solution to the life-threatening flooding in their neighborhood,” she said.

This article originally appeared in The Homepage.

Recent Comments