It comes down to the Mon-Oakland Connector (MOC): a boondoggle dreamed up by some of Pittsburgh’s universities and foundations that would have ruined a popular motor-free trail through Schenley Park and established a foothold for wiping my neighborhood (Four Mile Run) off the map.

Why dwell on a project that was discredited and shelved years ago? If you have to ask, it’s because you forgot how the MOC came to be old news. Two men figure prominently in the story—and both are currently running for mayor in Pittsburgh’s Democratic primary.

During Ed Gainey’s first run, he participated in a Zoom debate with the other mayoral candidates. Some of my Hazelwood neighbors and I got a chance to ask about their position on the MOC. Gainey didn’t seem familiar with the project, but showed interest in how we overcame efforts by MOC boosters to pit our neighborhoods against each other. After the debate, I emailed Gainey’s campaign inviting him “down The Run” to see the situation for himself. His wife Michelle replied and we made arrangements for visits to The Run and Hazelwood.

The first time I met Ed Gainey, about 35 of us from both neighborhoods walked with him from Four Mile Run Field into Junction Hollow and back. He asked questions, listened to our answers, and seemed genuinely concerned about our community’s problems. Before any of us mentioned hazardous conditions around the railroad trestle, Gainey noticed and inquired about piles of railroad spikes on the trail where they land after flying off the tracks.

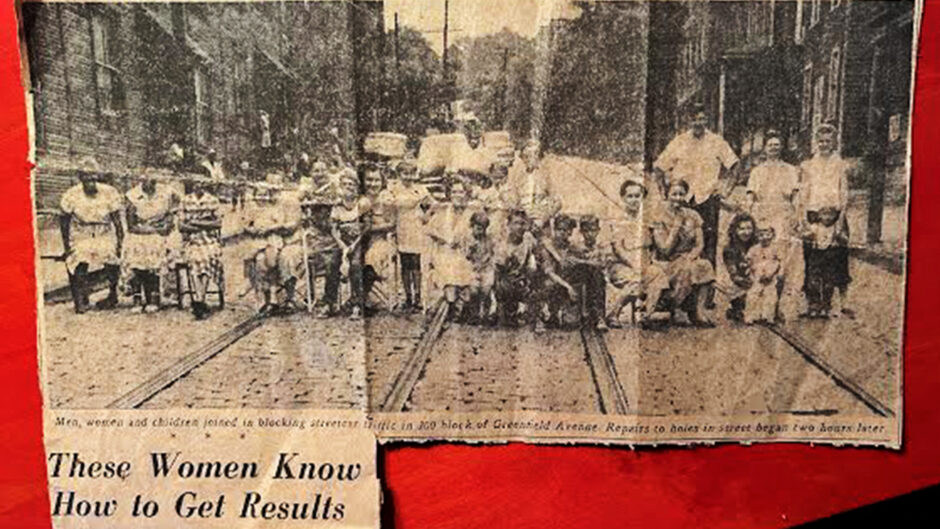

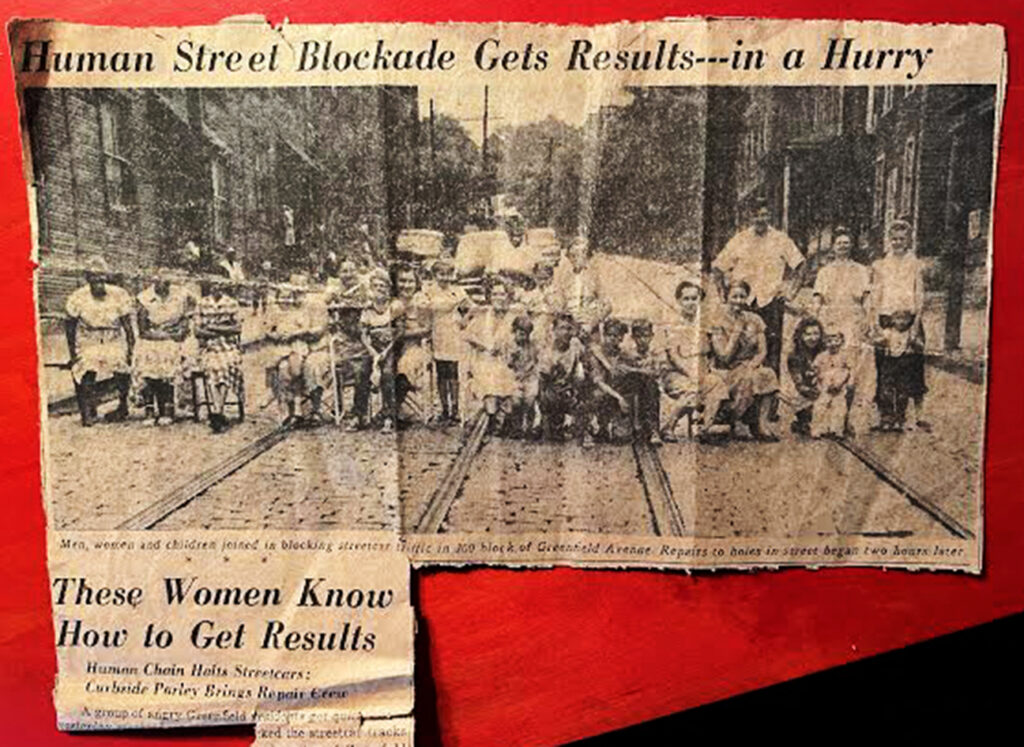

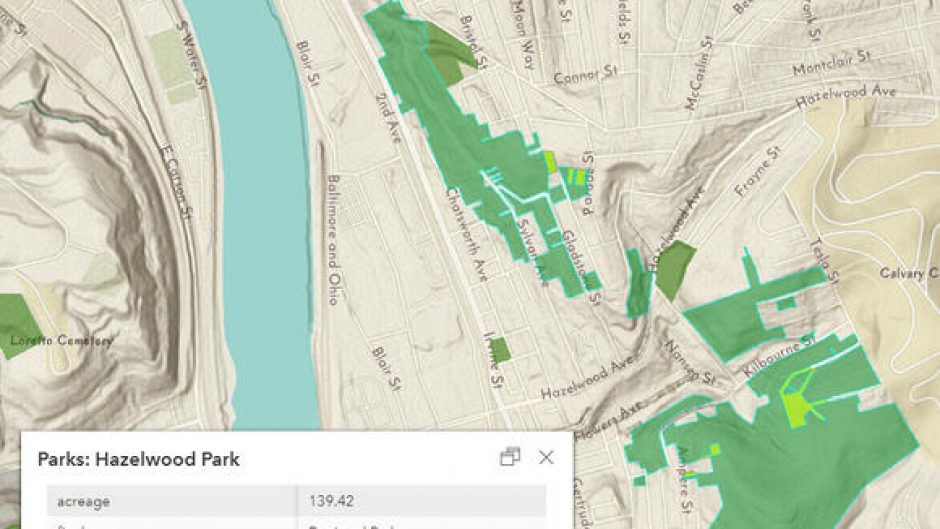

We talked about destructive flooding in The Run and how it’s worsened over decades as uphill neighborhoods—including Oakland university campuses—develop rapidly and tax the sewer system. When Run residents learned of plans for the MOC from a 2015 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article, those plans did not include flood control. Our city government and Pittsburgh Water were shamed into their Four Mile Run stormwater project only after media coverage of a harrowing 2016 flash flood—in which emergency responders had to rescue a father and son trapped on top of their car.

Ed Gainey made no big promises on his first visit to The Run, but soon adopted our cause as part of his campaign. Canceling the MOC was among the first actions he took in office.

Gainey’s challenger, County Controller Corey O’Connor, was our District 5 city council representative throughout our six-and-a-half year fight against the MOC. He watched my neighbors and me show up in force at public meetings, organize marches and press conferences, and file Right to Know requests. In conversations with Run residents he acted as though his hands were tied, the road a foregone conclusion. He was evasive at best when it came to answering our questions and providing information about the MOC. He flat-out lied to us on several occasions.

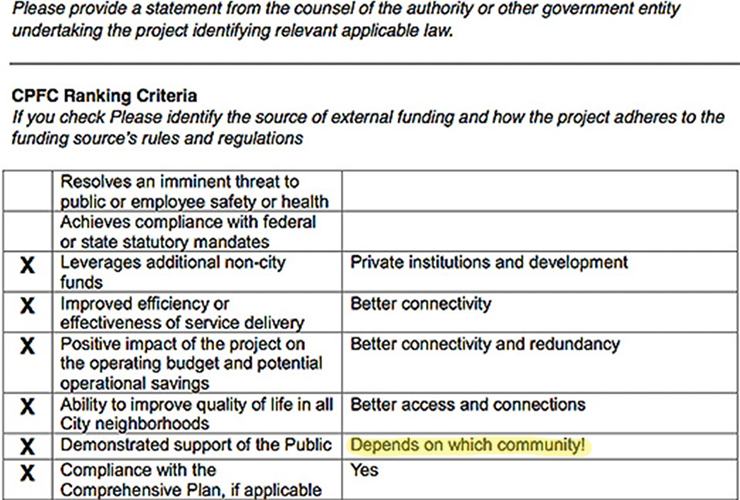

Corey O’Connor was having completely different conversations with some Hazelwood residents, asking or even pressuring them to publicly support the MOC. In 2021 he played a shell game with the project’s funding, crowing about having moved $4.15 million to different projects in other communities. Mysteriously, $4 million for the MOC reappeared in the 2022 budget before Ed Gainey canceled it. This stunt only showed that O’Connor could have chosen to defund the MOC at any time.

But I’m not writing this because of the status quo. Everyone knows about public officials who bend over backwards to represent the donor class. So many people told me and my neighbors, “You’ll never stop the road; there’s too much money behind it.” I’m writing this because Ed Gainey came to our neighborhood, listened to our issues, and made good on his promise to address them. That never happens!

Bucking the status quo has a cost. Ed Gainey canceling the MOC surely isn’t the sole reason for Pittsburgh’s money-starved news outlets cranking out hit piece after hit piece from the moment he took office. But it surely enraged the universities and Almono Partners when he rescinded their long-coveted private driveway. Although politicians are not known for being above reproach, I’ve never seen a local one criticized with such heavy bias.

By contrast, Corey MOConnor’s campaign has been showered with funds and fawning attention by the very same players who stood to gain from the scrapped shuttle road. I don’t believe it’s a coincidence that he chose Hazelwood Green as the place to announce his run for mayor.

The MOC may be dead and buried, but it’s still an issue in this election. It stands for sharp differences between these two candidates—in their approach to managing Pittsburgh’s resources and in their ethics. And the consequences are still playing out. After the MOC’s demise, Pittsburgh Water called off the green infrastructure part of their stormwater project in The Run. This year they announced the entire project has essentially been canceled, the funds moved elsewhere. The Run needs strong advocates—perhaps now more than ever.

Our neighborhood is a snapshot of each candidate’s priorities demonstrated through their actions. Pittsburgh can choose a mayor who returns to business as usual at our expense, or a mayor who actually tries his best to represent us. Your neighborhood’s issues might be different, but they deserve the same attention Ed Gainey has given us.

For me, the choice is as clear as it ever gets. I haven’t forgotten the MOC, and I certainly haven’t forgotten that Ed Gainey showed up for our community.

Recent Comments