by Marianne Holohan

Residents of The Run and community partners met at Zano’s Pub House on June 9 to discuss next steps for addressing ongoing flooding problems in the neighborhood. The meeting was called because Pittsburgh Water recently announced that they were pausing the long-awaited flood mitigation project slated to begin in 2025.

Anne Quinn, a Greenfield resident who leads the Mon Water Project, a water advocacy nonprofit, led the June 9 meeting.

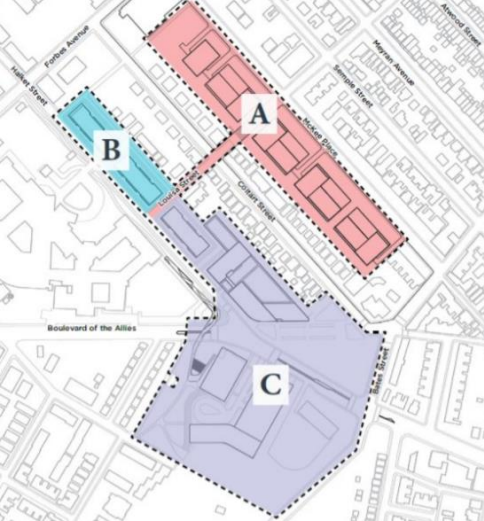

She started with an overview of why The Run continues to flood. She explained that stormwater from uphill communities — Oakland, Greenfield and Squirrel Hill — flows through The Run toward the Mon River. When heavy rainfall occurs, the volume of stormwater overwhelms the system, leading to destructive flash flooding. The Run has two “bowls” where flash flooding occurs: one near the playground on Boundary Street and the other on Saline Street near Big Jim’s restaurant.

Ms. Quinn pointed out that Panther Hollow Lake in lower Schenley Park poses a threat to The Run. The dam intended to contain the lake does not meet legal requirements and is in danger of failure. Should the dam fail, water from the lake would rush into Panther Hollow and The Run, further overwhelming the stormwater system and endangering residents.

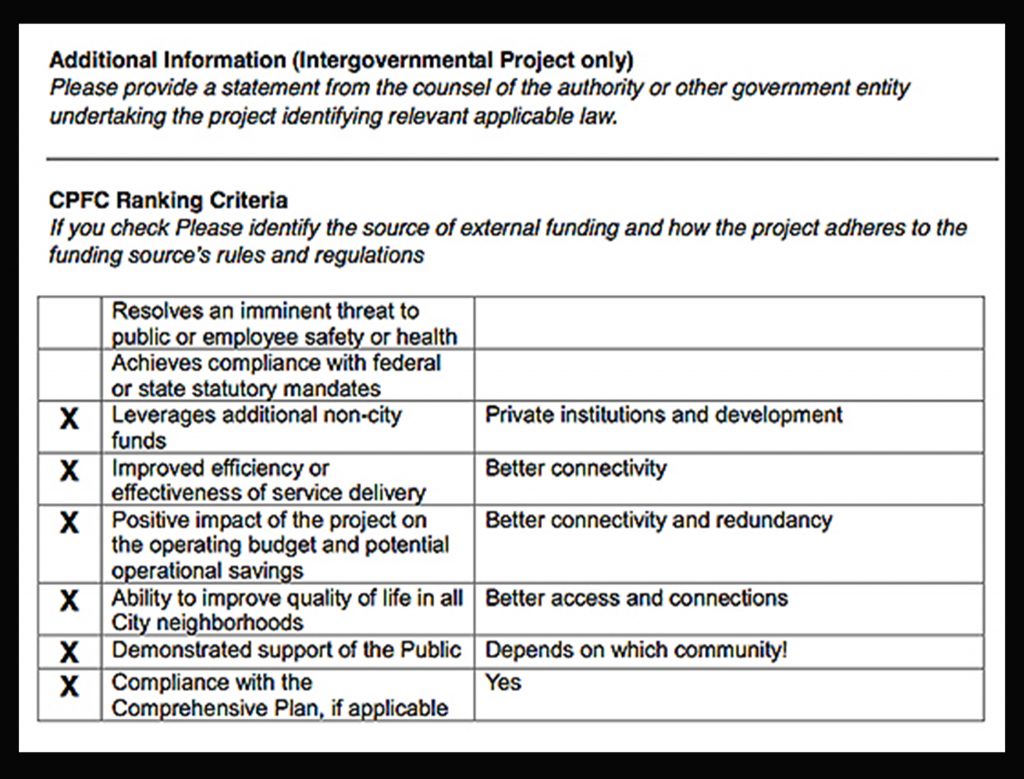

The Run has been plagued by destructive flooding for decades. Periodic flash floods block access to the neighborhood and threaten residents’ safety. Pittsburgh Water initiated a flood mitigation project in 2017 that was slated to include the installation of high-capacity piping as well as green infrastructure. In 2022, Pittsburgh Water announced that they had scaled back the project to remove green infrastructure components, and in April 2025, they announced the indefinite pause of the project.

At the June 9 meeting, Ms. Quinn said the installation of bigger pipes is the main solution to The Run’s flooding problem. Building a new stream through Junction Hollow would also allow excess water to flow from Panther Hollow Lake to the Mon River without pooling in The Run. Both of these solutions were included in the initial project design that has now been paused. She also urged residents of uphill communities to mitigate their contributions to stormwater runoff with more green space and permeable surfaces.

After Ms. Quinn spoke, Ziggy Edwards and Ray Gerard of Junction Coalition provided a timeline of flooding issues in The Run and Pittsburgh Water’s troubled mitigation project. Ms. Edwards and Mr. Gerard have reported extensively on these issues. They explained that a flash flood in 2016 left a man and his young son trapped on the roof of their vehicle on Saline Street. Emergency responders had difficulty reaching them because of the rushing flood waters. They also described the lack of transparency from Pittsburgh Water when communicating changes to the project over time.

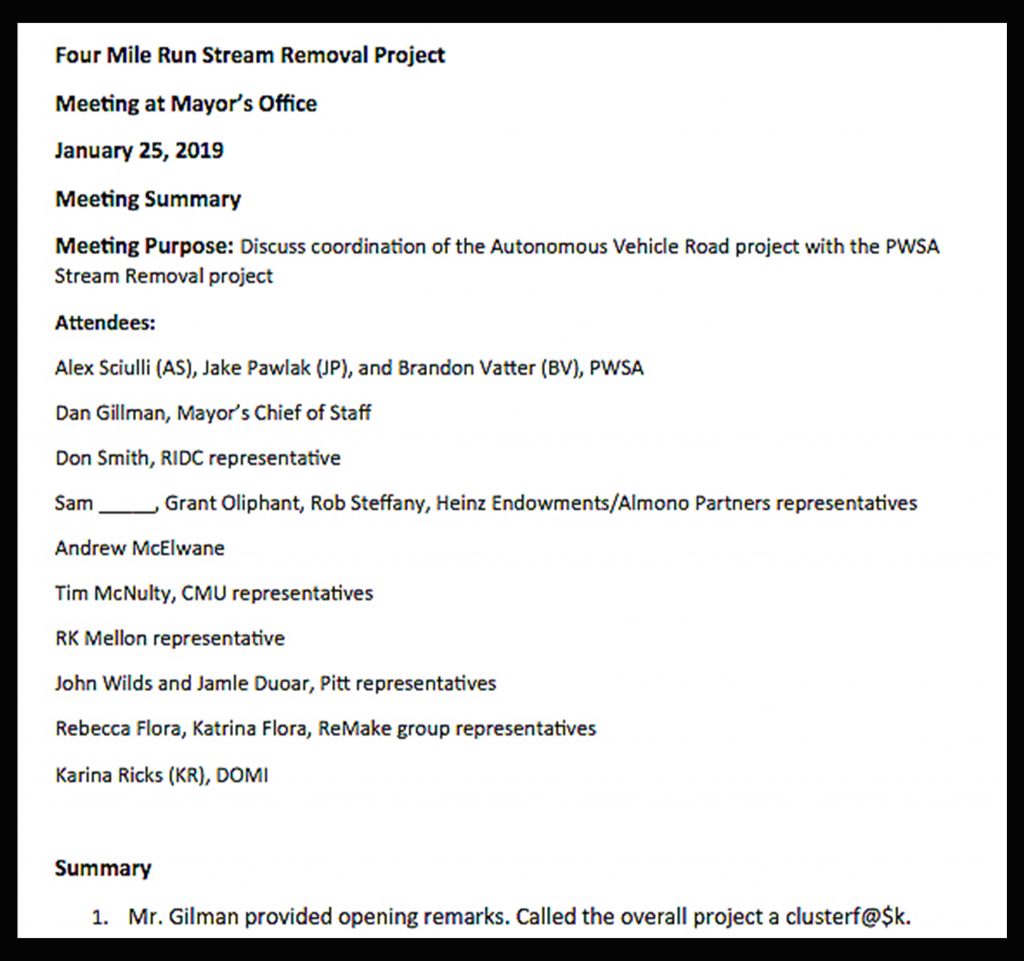

“The project … suffered from inadequate goals and self-defeating constraints,” Ms. Edwards said on June 14. She said the flood control features were tied to the Mon-Oakland Connector shuttle road project, also called MOC. Pittsburgh Water only admitted as much after Mayor Ed Gainey canceled it in 2022.

“They said they had a model of their project without the MOC but never would show it to us,” she said, adding that only a third of the funding was slated for the core project in Schenley Park and The Run.

The ongoing lack of transparency from Pittsburgh Water has angered longtime residents of The Run who have spent thousands of dollars repairing flood damage. One resident, Laura Vincent, remembered a 2022 community meeting held at the former Operating Engineers Union Hall. At that meeting, she said, a representative of Pittsburgh Water “had the nerve to tell us to be patient.”

Ms. Vincent, who owns two properties in The Run, has been waiting for decades for Pittsburgh Water to address this problem.

Residents of The Run have disproportionately shouldered the financial burden of the flooding. According to Ms. Quinn, residents face rising water utility fees while PennDOT, owner of the Parkway East bridge over Four Mile Run, does not pay any fees to offset the bridge’s substantial contributions to stormwater runoff. This further exacerbates flooding in The Run.

Additionally, residents and other ratepayers have supplied the $8.7 million already spent on the paused flood mitigation project. These funds were used to draw up a full design of the project, including green infrastructure. But Pittsburgh Water has yet to implement it.

District 5 City Councilor Barb Warwick, also a resident of The Run, called a press conference on May 23 during which Run residents and business owners expressed frustration toward Pittsburgh Water for failing to acknowledge the urgency of the project.

As the June 9 meeting came to a close, residents discussed next steps to advocate for the stormwater project. Ms. Quinn encouraged residents to keep pressuring Pittsburgh Water and elected officials. She included Democratic mayoral candidate Corey O’Connor, who indicated at a recent neighborhood meet-and-greet that he considers the stormwater remediation project in The Run a “passion project” of his.

In the meantime, Run residents and business owners are bracing for another flash flood season and hoping their worst fears won’t become reality before Pittsburgh Water finally decides to take action.

Marianne Holohan is a resident of The Run. She also serves on the board of the Greenfield School PTO and is an Allegheny County Democratic Committee rep for the 15th Ward – District 9.

Recent Comments