Continuing fallout from a February 3 derailment in East Palestine, Ohio, of a Norfolk Southern freight train carrying toxic chemicals is drawing concern from nearby communities and beyond. On March 7, Mayor Ed Gainey issued a joint statement with five other western Pennsylvania mayors that emphasized continued monitoring of the situation “for any potential short-term or long-term impacts we may see in order to do all we can to protect our air and water for our residents and the region’s wildlife.”

Trying to reassure constituents in a “potential blast zone”

The mayors’ statement also pledged to work with Pittsburgh City Council to “gain a clear picture of the state of rail infrastructure so we can safeguard our communities and hold the railroad companies accountable for any repairs that may need to be made.”

City Council released its own statement on March 7, noting that “as many as 176,000 Pittsburghers live within the potential blast zone of a similar derailment.” They called for stricter regulation of rail carriers and harsher penalties for safety violations.

The council also expressed support for new federal legislation that tightens the rules around trains carrying hazardous materials and expands the “high-hazard flammable” category.

The U.S. Senate’s Railway Safety Act of 2023, introduced on March 1, includes provisions that seem aimed at reversing a trend toward poor working conditions at rail companies. For instance, it would set minimum time requirements for rail car or locomotive inspections.

These reforms push back against an industry laser-focused on speed. Over the past decade, rail companies slashed 30% of their workforce, including safety inspectors, while running longer and heavier trains.

The high price of efficiency

Matt Weaver, a union member and Ohio legislative director of Brotherhood of Maintenance of Way Employees, said in a February interview on the Working People podcast, “It goes back to precision scheduled railroading —the business model of the railroad industry for doing more with less.”

Mr. Weaver said his friends who inspect cars have told him standards changed “from two guys inspecting a car and having four or five minutes to do so; now it’s down to one guy pushing for…less than 90 seconds, as little as a minute.”

In addition, rail companies have opposed updating trains’ braking systems to electronic controlled pneumatic brakes (ECB). While most trains have air braking systems that stop individual cars, ECB systems use electronic signals to stop the entire train.

ECB brakes slow and stop trains up to 70% faster, but in 2018 the rail industry lobbied to repeal a Department of Transportation train safety rule requiring ECB installation on trains carrying flammable and hazardous materials.

After the East Palestine derailment, residents near the Pennsylvania border were evacuated while Norfolk Southern executed a “controlled burn” of hazardous chemicals from some of the derailed cars on February 6.

The resulting black cloud towered hundreds of feet into the air; passengers on a commercial flight spotted it. Within 48 hours, the evacuation order was lifted and Ohio governor Mike DeWine announced, “Air quality samples in the area of the wreckage and in nearby residential neighborhoods have consistently showed readings at points below safety screening levels for contaminants of concern.” But some East Palestine residents who returned home began to report symptoms like sore throats, burning eyes, nausea, and rashes. The Ohio Department of Natural Resources said the chemical spill had killed about 3,500 fish in nearby streams.

Pittsburgh has been lucky so far

Pittsburgh has had its share of derailments in recent years. In 2018, seven double-stacked Norfolk Southern railroad cars derailed near Station Square. No injuries were reported, and the spilled cargo consisted of consumer goods including mouthwash and diapers.

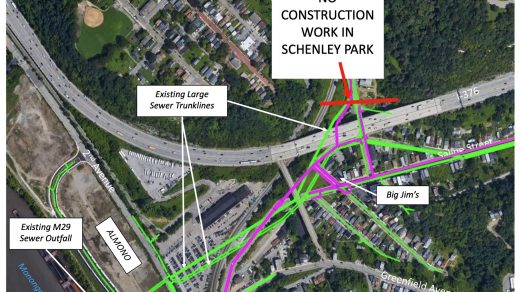

In 2015, 13 hopper cars went off the rails in Hazelwood near Irvine Street. Police officers and firefighters responded to the derailment as a possible hazard, but soon determined the cars were empty.

This same rail line travels through The Run and a tunnel on Neville Street in Oakland, which runs directly beneath one of the densest neighborhoods in the city. A 2015 report from PennEnvironment lists the 15213 Oakland ZIP code among its “top 25 PA zip codes with the largest populations living in the possible evacuation zone.”

In early 2016, a train carrying oil products decoupled along these tracks just before entering the tunnel. Observers recorded several cars marked with hazard placards identifying flammable cargo. Fortunately, the coupling broke as the train headed uphill and the disconnected cars’ brakes worked properly. Had the brakes failed, this portion of the train could have rolled backward and derailed at the first turn in Junction Hollow. A similar decoupling in 2013 caused an explosion in Lac-Mégantic, Quebec that killed 47 people and destroyed the town.

Train derailments are not inevitable

Derailments are more common than people might think, although they rarely involve fatalities. The Department of Transportation has recorded more than 12,400 train derailments over the past decade; of these accidents, around 6,600 tank cars were carrying hazardous materials and 348 cars released their contents, according to the Associated Press.

But as PennEnvironment’s report points out, “[T]rains carrying hazardous materials like crude oil often travel through highly populated cities, counties and neighborhoods—as well as near major drinking water sources.”

The combination of eroded safety regulations and close proximity is a recipe for a disaster like the one in East Palestine.

At a February 23 news conference, National Transportation Safety Board Chair Jennifer Homendy called the derailment “100% preventable” and said, “We call things accidents—there are no accidents. Every single event we investigate is preventable.”

Recent Comments