On Oct. 3, about 65 people gathered at the City Reformed Presbyterian Church in The Run to discuss solutions to the neighborhood’s flooding. The discussion has occurred repeatedly over the years, at times in the same basement assembly room when it was owned by International Union of Operating Engineers Local 95.

But this time, the crowd was somewhat different. It included members of 17 nonprofit organizations and community groups; 10 city, county, and state-level governmental agencies; and seven elected officials and their staff.

“We have quite an audience here today — individuals who, I would say, are the decision-makers,” said Mon Water Project founder Annie Quinn, who organized the event. She said she was excited to bring them together with groups pushing for flood relief and green infrastructure.

Not a revolutionary request

Water management problems affect The Run and Pittsburgh as a whole, Ms. Quinn explained. Pittsburgh starts at a disadvantage compared to cities like Philadelphia, which have better soil and less hilly terrain. Like many cities, “We grew systems without growing the infrastructure to support them,” she said.

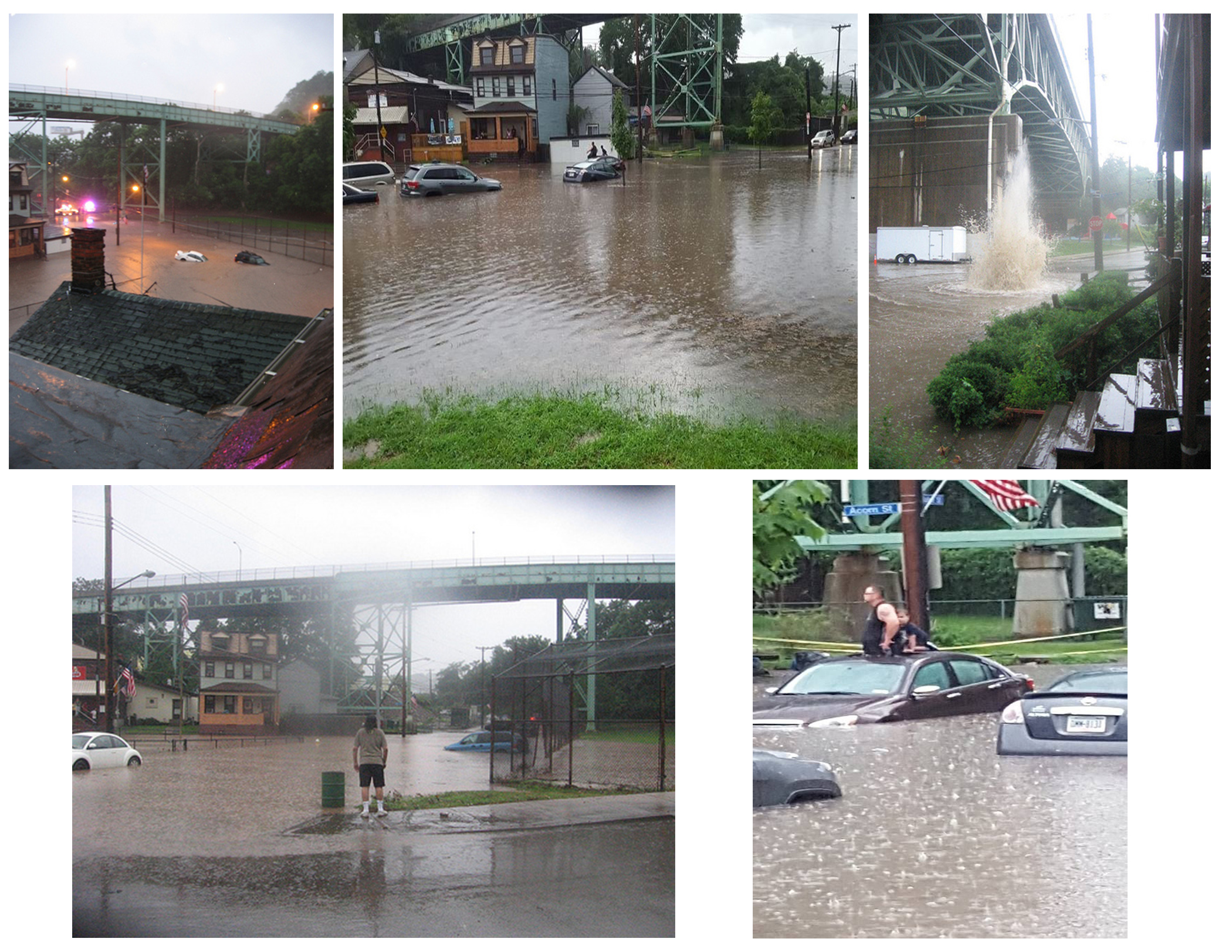

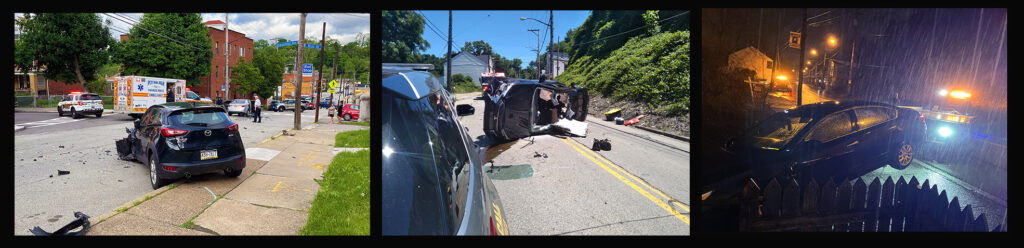

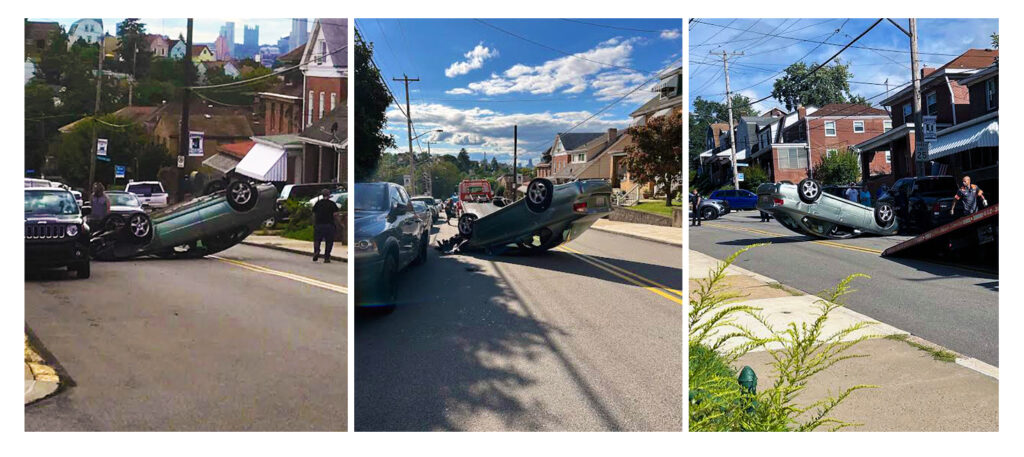

As a result, every wet-weather event tests the limits of Pittsburgh’s water infrastructure.

“Our sewers overflow in even a tenth of an inch of rain,” Ms. Quinn said. “There is the possibility that The Run will continue to flood, and stormwater issues will be happening right here. But I am not done with my work until the Monongahela River is overflow free as the result of Four Mile Run no longer being the fourth-largest overflow in the city.”

She said Pittsburgh Water (also known as PWSA) has already completed much of the work toward solving this problem.

Ms. Quinn named five solutions she called “project areas”:

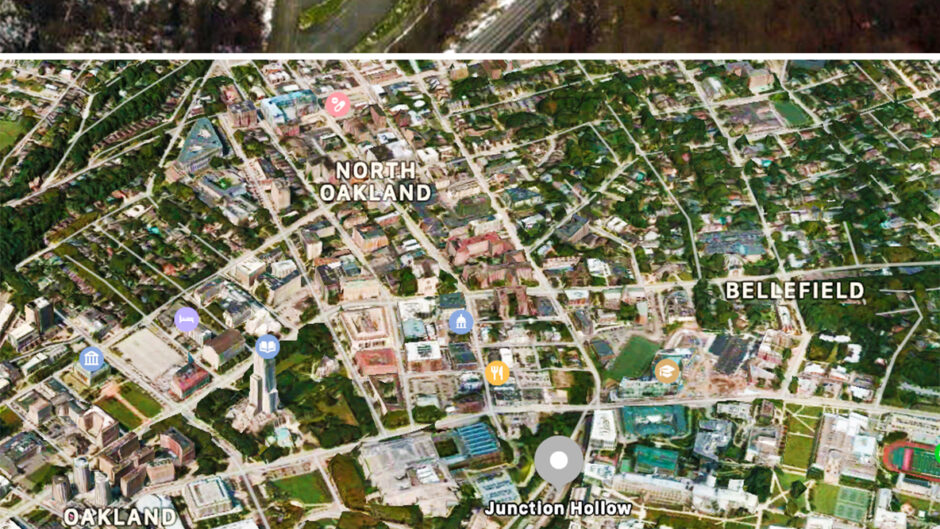

1. Separation of sewers in The Run. This means installing a dedicated pipeline for stormwater beneath the neighborhood’s streets. Ms. Quinn described it as “the project that has to happen for anything else to happen.”

2. Restoration of Panther Hollow Lake. The once-popular attraction is less than 4 inches deep, plagued by algae blooms and a recent fish kill. Pittsburgh’s Department of Public Works is applying for permits to do some of the work needed, but a much larger-scale restoration was already designed.

3. Uncovering and restoring buried streams. This would prevent two spring-fed streams from adding about 68 million gallons into the sewer system each year, allowing them to follow their own courses. Ms. Quinn noted that this is similar to work done on Nine Mile Run in Frick Park. “I am not asking for something revolutionary,” she said. “I am asking for a copy-paste of a restoration project that has already occurred and been one of the most successful restoration projects in the country.”

4. Infrastructure in upstream neighborhoods to direct stormwater to storage that could be built under places like Magee Field. Ms. Quinn said ALCOSAN has already identified Magee Field as a good location.

5. Removal of parkway stormwater runoff from the sewer system. PennDOT is planning major construction projects along I-376 Parkway East over the next few years, so now is the time to study how water runoff from the parkway can be diverted.

Pittsburgh Water had planned a $41 million stormwater project in The Run and nearby Schenley Park that included project areas 1–3. After the Mon-Oakland Connector shuttle road planned for the same location was canceled in 2022, Pittsburgh Water scaled back the project to only area 1. Despite reaffirming its commitment to Run residents at that time, Pittsburgh Water eliminated all funding for construction in late 2024.

Renewed determination

After her talk, Ms. Quinn invited Run residents to share their experiences.

Laura Vincent has lived in the neighborhood for 20 years. She remembered the floods starting in about 2006 and occurring every two years until the latest one in 2021. She said she and her husband replaced the hot water heaters, furnaces, washers, and dryers in their home and rental property three or four times. Eventually, they installed backflow valves and rubber membranes that keep both basements dry. But many of their neighbors lack the resources to do so.

“I can’t tell you how many times my husband, at 8:30 in the evening, has run around to all my neighbors to help them re-light pilot lights on their water tanks so at least after they’re done cleaning up their basements they can take a shower,” Ms. Vincent said.

Marianne Holohan, a 13-year resident, talked about raising her two children in The Run. “Part of their story of growing up is, ‘Be careful going outside after it rains because there’s sewage everywhere.’” Ms. Holohan added, “You know, people ride their bikes through this neighborhood constantly. They could also be the victims of the next major flood. It is, in fact, irresponsible to not do any of these projects.”

District 5 City Councilor Barb Warwick thanked Rep. Dan Frankel and Sen. Jay Costa for attending. She emphasized that many of her neighbors in The Run told her after PWSA pulled its funding, “‘They were never going to do that project. They were blowing smoke the entire time.’”

“That is so depressing,” she said. “Annie, just listening to you talk right now — you have galvanized me. These projects were promised to this neighborhood, and they need to get done.”

Working with PennDOT

During the walk through The Run and Junction Hollow, Rep. Frankel spoke with us about state-level solutions.

One obstacle to completing project area 5 is that Pennsylvania’s Department of Transportation (PennDOT) doesn’t perform maintenance beyond the boundaries of a state highway, except as needed to keep the highway structurally sound.

In addition, PennDOT does not pay a stormwater fee. According to Rep. Frankel’s office, government agencies normally don’t have to pay taxes, which the commonwealth says include stormwater fees. But the Pennsylvania Supreme Court is currently considering whether a stormwater management fee is a tax or a fee for service. Pennsylvania does pay fee-for-service charges. The case, Borough of West Chester v. Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education, was argued in 2024; a decision is still pending.

Rep. Frankel co-sponsored legislation introduced by State Reps. Justin Fleming and Dave Madsen. It would require Pennsylvania to pay its fair share of stormwater management fees to local municipalities.

He wrote in an Oct. 10 email, “This is an all-hands-on-deck problem, and I’m glad to help the city of Pittsburgh and the Mon Water Project get every state dollar possible to solve it.”

This article originally appeared in The Homepage.

Recent Comments