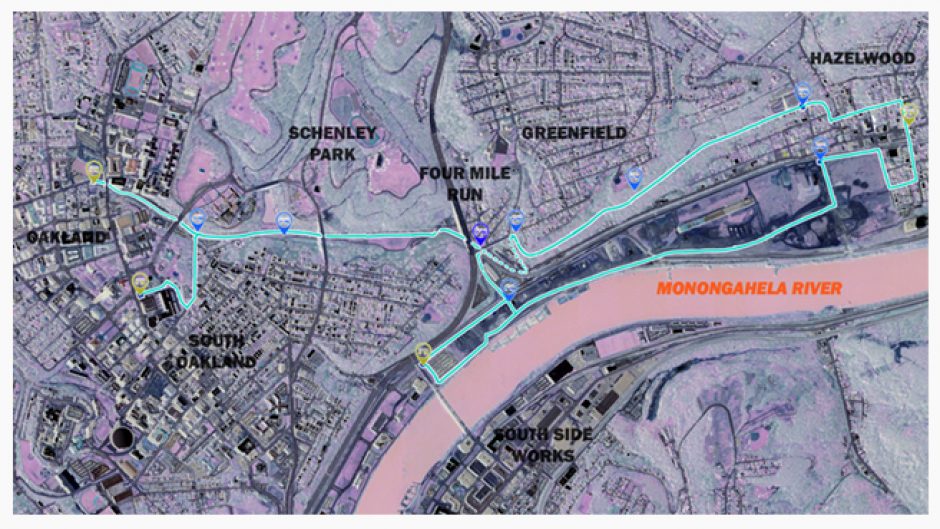

On May 6, Pennsylvania State Representative Ed Gainey met 30-40 community members in The Run. Rep. Gainey, who hopes to win the Democratic primary in the race to become Pittsburgh’s next mayor, heard Run residents describe the severe flooding that plagues their neighborhood. They also discussed the city’s plans to widen Swinburne Bridge with a dedicated lane for shuttles between the Hazelwood Green development and the Oakland universities, a controversial project known as the Mon-Oakland Connector (MOC). One small business and several families located near the bridge have received letters from the Department of Mobility and Infrastructure invoking eminent domain.

“The [Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority’s (PWSA’s)] stormwater project is designed around the MOC,” said Ziggy Edwards of The Run. “Their design doesn’t fix the flooding, and [PWSA] won’t show us a model without the MOC.”

The crowd made its way to the neighborhood’s recreational facilities beneath Interstate 376, which include a recently reopened basketball court and a dilapidated playground that was partially barricaded after a child was injured. Several parents from The Run mentioned a 2018 playground closure due to concrete chunks falling from the underside of the highway. Crews have since installed netting under that section of 376.

As the group continued toward the Junction Hollow section of Schenley Park, Rep. Gainey asked questions about the MOC, for which DOMI plans to build a new road through Schenley Park. Residents peppered him with information, describing the lack of genuine community support for and involvement in the project. For example, Run residents described how they learned of the plan from a 2015 article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

“There are certain people in Hazelwood… organizations who knew or heard about what’s going on and that support [the MOC],” said James Cole of Hazelwood. “But the people IN the neighborhood, FROM the neighborhood, live, sleep, breathe, interact with the people in the neighborhood… nobody’s for it.”

The Hazelwood Green development is owned by Almono Partners, which plans to operate the proposed MOC shuttles.

“I’m not against new people coming to Pittsburgh; as a matter of fact, we want that level of growth,” Gainey told the group. “But it shouldn’t be at the expense of people who’ve been here forever and a day. If you want to know what’s going to bring this city together in a unified way, it’s because you’re fighting that power. It’s [saying], ‘I’m not gonna be removed. I’m NOT gonna be removed.’”

Rep. Gainey continued his walkthrough in Hazelwood. As the group re-formed at the corner of Hazelwood and Second Avenues, he spoke with Pastor Lutual Love, Sr. of Hazelwood about development of the 4800 block of Second Avenue.

“We were expressing our disapproval of the current design [for the proposed development],” Pastor Love recounted. “We’re trying to influence the City to change the current RFP to include retail space—such as a grocery store, high-tech laundromat, or credit union—that offers services to lower-income people, that’s more family oriented. There’s a lot of one-bedroom housing being proposed.”

Rep. Gainey mentioned his visit to The Run and Hazelwood during a May 10 meet-the-candidates Q&A session hosted online by Voter Empowerment Education and Enrichment Movement (VEEEM) Pittsburgh. “I would not be for the Mon-Oakland Connector,” he said. “I was down in The Run, I was down in Hazelwood, and I was in Greenfield… They don’t want the Mon-Oakland Connector; they don’t feel it’s going to benefit them.”

All three candidates challenging Pittsburgh mayor Bill Peduto—Rep. Gainey, Tony Moreno, and Mike Thompson—said they would reallocate the $23 million of capital money to more urgent neighborhood infrastructure needs and prioritize flood mitigation.

Photo from Gainey mayoral campaign social media post

Recent Comments