On July 14, Pittsburgh’s Department of Mobility and Infrastructure (DOMI) hosted a virtual meeting about plans to tear down and rebuild Swinburne Bridge in lower Greenfield. The bridge, built in 1915 and rehabilitated twice, is in poor condition and had its weight limit lowered to 21 tons in 2014. According to the Swinburne Bridge project page on Engage PGH, it serves the communities of Four Mile Run (“The Run”), Greenfield, South Oakland, and downtown. The bridge connects Swinburne Street in South Oakland to Greenfield Avenue in lower Greenfield. DOMI said the city is working with the Federal Highway Administration and the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) on the project.

About 65 attendees logged in to the meeting, plus an in-person “watch party” of 20 on the deck at Zano’s Pub House. Barb Warwick, who lives in The Run and is running for Pittsburgh City Council’s District 5 seat, facilitated questions from the group at Zano’s.

Representatives from DOMI, PennDOT, and private construction firm Alfred Benesch & Company all acknowledged that work on Swinburne Bridge will profoundly affect The Run. A significant portion of the neighborhood—and the only street providing vehicular access to it—lies directly beneath the bridge. DOMI painted a rosy picture of plans to minimize disruptions to the community while completing the project. But several aspects of the meeting fueled continuing mistrust among residents, who have years of experience with the city treating them as roadblocks to development projects that serve private interests.

A double standard for safety

DOMI project manager Zachary Workman responded with unequivocal commitment to unspecified comments in the chat about bridge safety concerns. “We are absolutely not going to have another bridge collapse,” he said, referring to the January 2022 collapse of Fern Hollow Bridge. “That can’t happen, and we’re not going to let it happen.”

Mr. Workman had more guarded answers to concerns raised by affected residents. He said DOMI is aware of dangerous traffic conditions along Greenfield Avenue that led to repeated requests for traffic-calming measures. “It’s definitely something that’s on DOMI’s radar for improvements in the future but they are going to be—it’s something that we’ll—it’s in the long-range plan as resources become available … It’s going to be a little while still and beyond the scope of this project.”

Project plans include a traffic signal at the intersection of Swinburne Bridge and Greenfield Avenue. When asked if a traffic signal could be installed sooner than the projected fall 2026 bridge completion, DOMI chief engineer Eric Setzler told residents, “Unfortunately, I think, it’s being constructed as part of this project. I certainly understand your desire to see it as soon as possible. I could definitely see that being beneficial, but it’s part of the project so it’s going to have to come at the same time as the rest of the project.”

“Property takes” not ruled out

Also in contrast with DOMI’s commitment to never let another bridge collapse, they went out of their way to avoid firm promises concerning homes and businesses beneath Swinburne Bridge.

Dana Provenzano, who owns two affected properties including Zano’s, asked, “You’re saying you’re not taking any properties, correct?”

“Our preliminary investigation into the demolition and construction is that this bridge can be demolished and rebuilt without taking homes,” Mr. Workman responded. “We’re in preliminary engineering, but that seems to be feasible.”

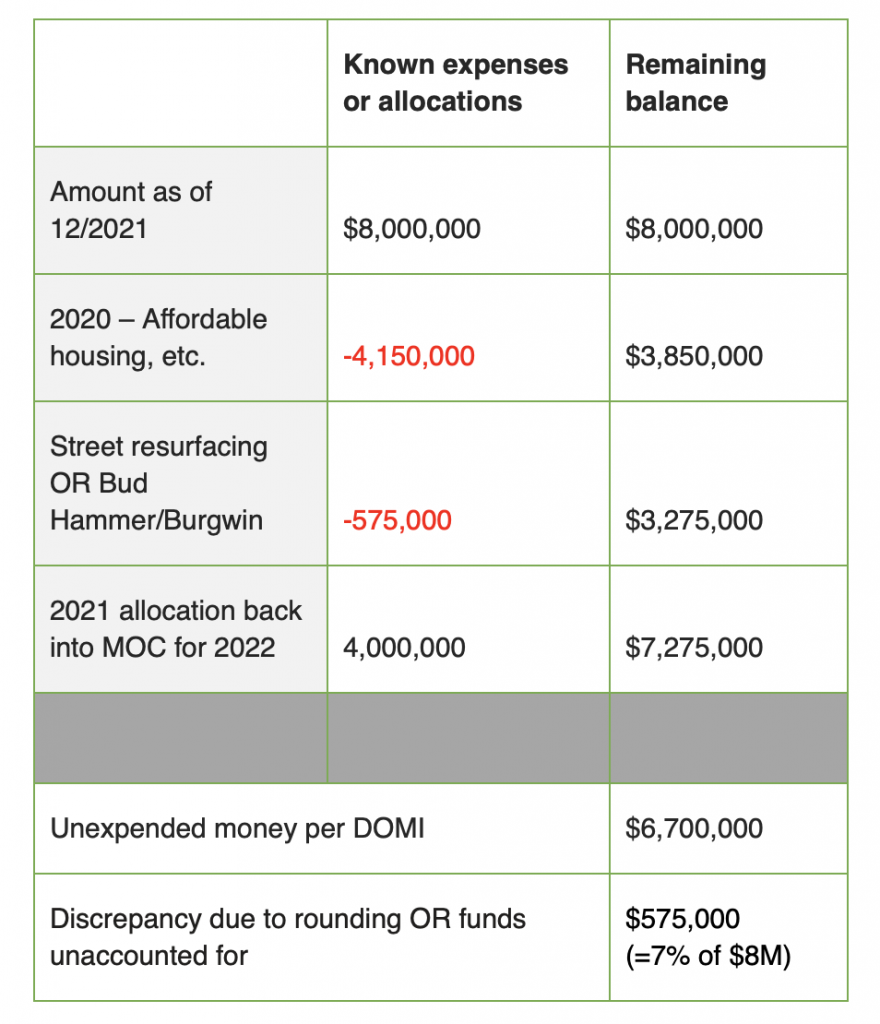

Mayor Ed Gainey emphatically promised residents that the city would not take anyone’s home (see video) at a February 17 meeting in Hazelwood where he announced an end to the Mon-Oakland Connector (MOC) shuttle project. Affected communities including The Run heavily opposed the MOC, which lives on as a purported bike and pedestrian trail that still enjoys a substantial yet murky budget. DOMI has long envisioned Swinburne Bridge as part of the MOC shuttle route.

Asked whether Mayor Gainey’s promise changed plans for the bridge, Mr. Setzler said it “did help us clarify what we were doing for this project … Once we knew [the MOC shuttle] was no longer part of the equation we could home in on bikes, peds, and vehicles.” He did not specify what kind of vehicles.

Mr. Setzler explained that a couple of years ago, DOMI was considering new alignments that would eliminate the sharp turn on the northern end of the bridge. “However, as we were looking at it we realized pretty quickly that any different path for the bridge would require right-of-way, require property takes—by definition, because you’re going over a place where there wasn’t a bridge before.”

Pittsburgh’s 2023 capital budget includes $100K for right-of-way acquisition associated with Swinburne Bridge, but Mr. Setzler said that setting aside funds for this purpose is standard procedure on this type of project. “We believe we can avoid taking property, and that is our goal,” he added.

A shared-use path to nowhere?

Many MOC critics believe profiteers who dreamed up the plan are regrouping to use this bridge replacement as cover for an eventual revival of the community-erasing shuttle road.

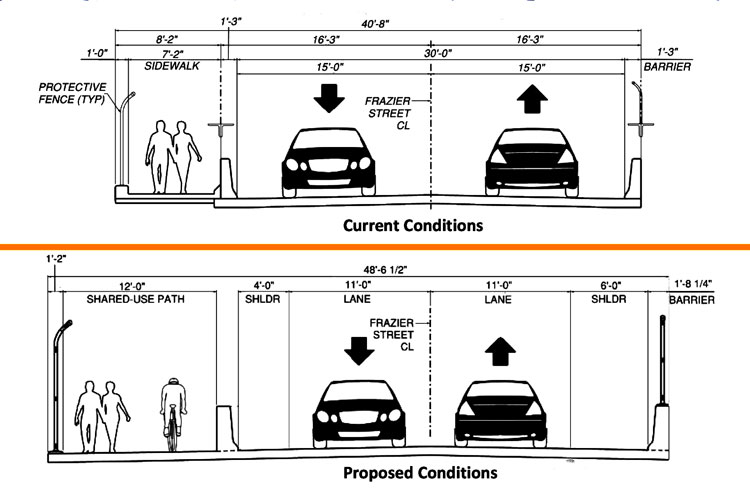

Mel Packer of Point Breeze said he has ridden his bike across Swinburne bridge and appreciates “how dangerous it can be once you get onto the Oakland side.” Although he welcomed the “shared-use path” in DOMI’s presented design, Mr. Packer questioned why the path suddenly stops in that treacherous location.

“I’m old enough to remember we had a bridge to nowhere once,” he said. “I feel like this is the bike path to nowhere … What are you not telling me? Why would we build a path that wide across the bridge when it’s impossible to widen Swinburne [Street]? We know it’s impossible—I mean, it would cost many millions of dollars; you’d have to buy properties up on the hill, build a wall 50 feet tall. No one’s going to do that.”

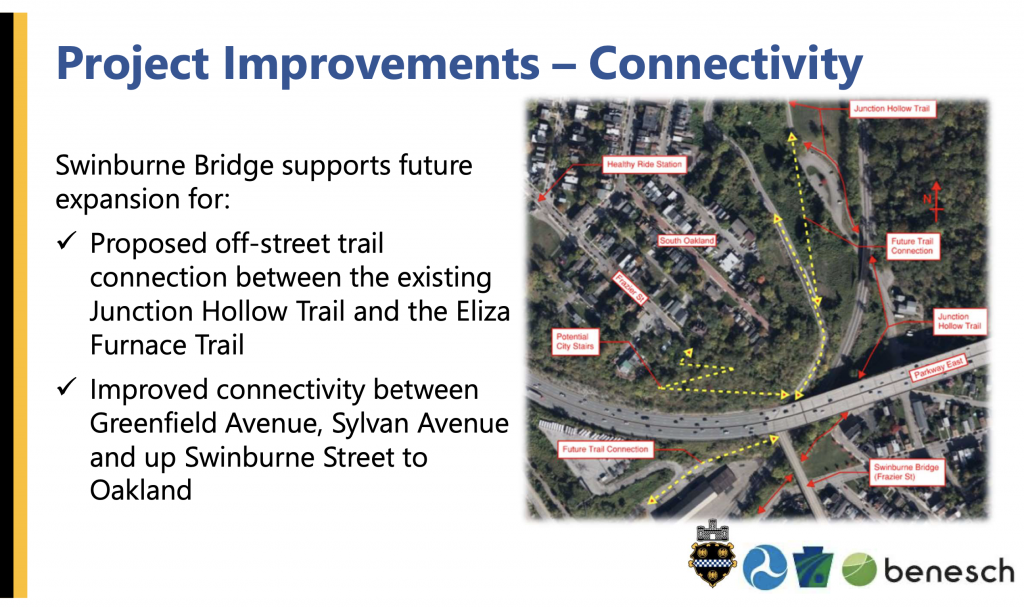

Mr. Setzler responded, “The shuttle has been put aside; that is done. But we’re really looking at the bike-ped connection, and a couple of things we showed on the screen [slide 13 of the presentation]—just to be clear, they’re not part of this project.”

He described a desired off-street connection between the Eliza Furnace trailhead and Swinburne Bridge where the path ends. This could allow cyclists and pedestrians to travel “into the heart of Hazelwood” without navigating the five-way intersection at Greenfield Avenue/Second Avenue/Irvine Street/Saline Street.

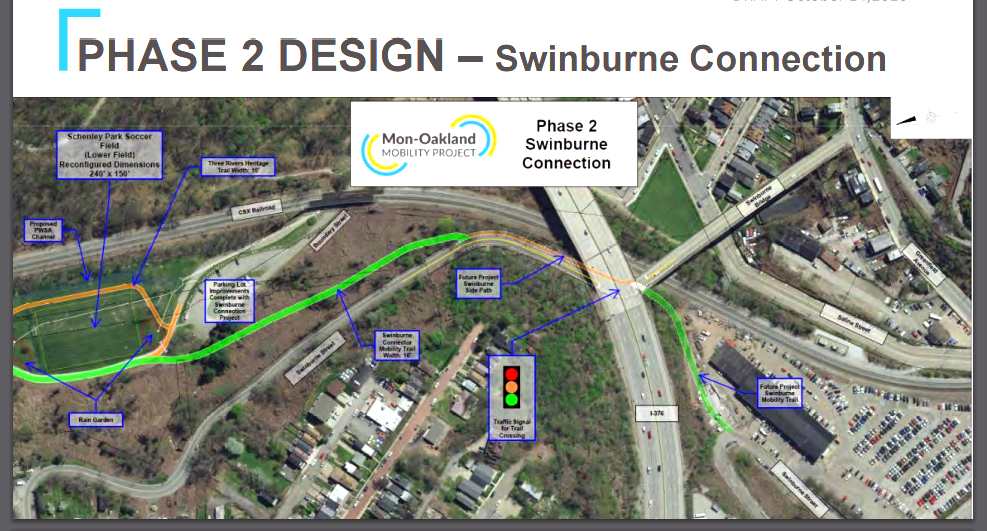

An additional connection was not listed in the slide’s text. “There’s also a potential to maybe get on a trail on the other side of the road [where the path ends on Swinburne Bridge] and get back down into [Schenley] Park and go up through the park past the soccer fields and get into Oakland,” Mr. Setzler said.

This route corresponds exactly with the “Swinburne connection” referenced in DOMI’s October 2020 presentation as “phase 2” of the MOC. The projected 16-foot-wide road was to traverse the same landslide-prone hillside with fragile soil conditions that prevent Swinburne Street from being widened.

DOMI’s presentation on the Swinburne Bridge did not include a slide with ideas for future traffic-calming measures on Greenfield Avenue, even though residents must face speeding traffic every time they walk between their houses and cars.

Rushing past design, community input

Rob Pfaffman, a prominent local architect, called the Swinburne Bridge project “a hidden opportunity to celebrate the Hollow, the community, the natural environment, and the trail of course running through it.” But he said that based on what he saw in the presentation, planners are disregarding that opportunity.

“You can’t have a design process where you’re already through preliminary design and you haven’t engaged the community,” Mr. Pfaffman commented. “[Design is] integral to a great project, and right now what you’re showing us is not that. It’s a Fern Hollow Bridge—which is basically expediting a project as quickly as you can and saying screw the design.”

The next public meeting is not scheduled to be held until 2023 or 2024—during “final design.”

Recent Comments