After Pittsburgh Regional Transit released the first draft of its Bus Line Redesign project on Sept. 30, Hazelwood resident Tiffany Taulton had one top concern: How will her son and his classmates get to school at Allderdice? The plan eliminates the 93 bus line and replaces it with routes that don’t have stops in Squirrel Hill, Shadyside or Lawrenceville.

“Without the 93 bus, there is no connection to Squirrel Hill that gets [students] to school on time and safely,” Ms. Taulton said on Nov. 13.

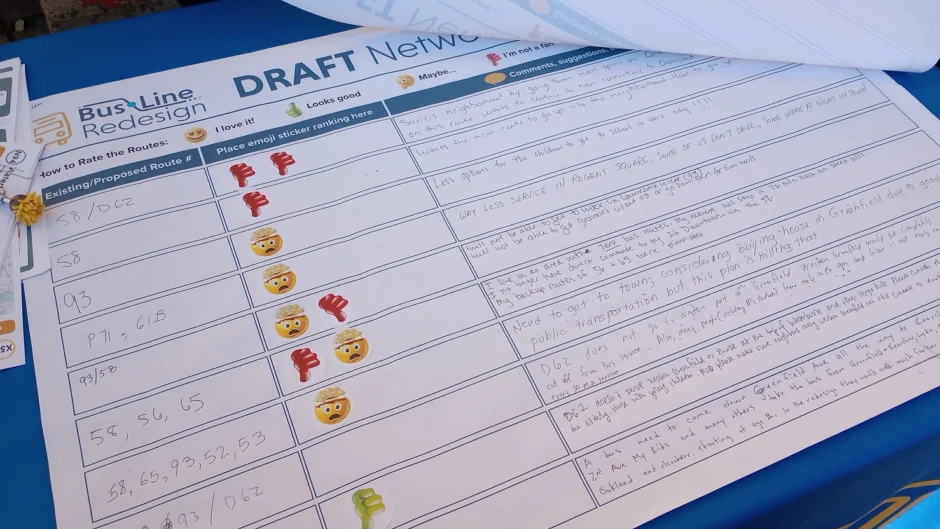

On Nov. 12, the agency formerly called Port Authority, now known as PRT, gave a presentation on their new plan to the Hazelwood community meeting — where they heard many similar concerns from Hazelwood residents.

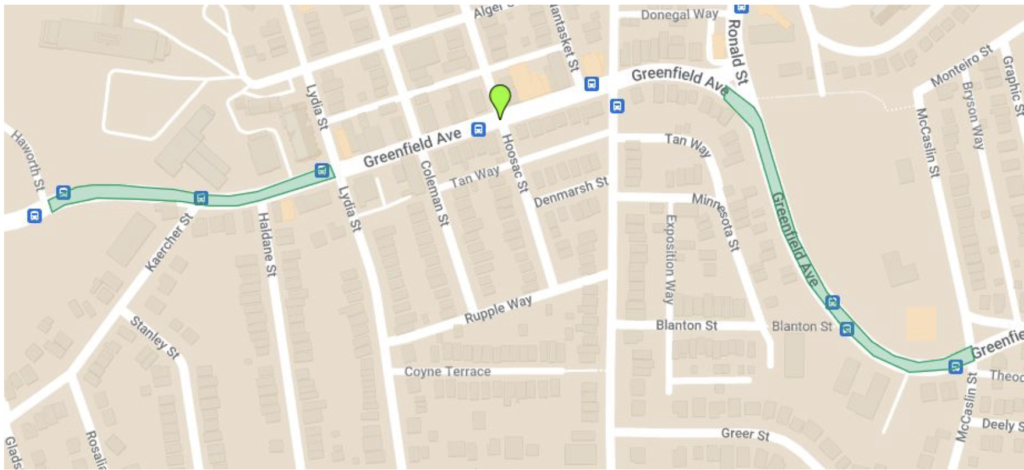

Proposed Hazelwood changes

About 35 people attended November’s monthly meeting in person and, another 20 used Zoom. Emily Provonsha, PRT’s manager of service development, said PRT is in its first phase of getting feedback about the proposed plan. As the weather gets colder, she said, they are planning fewer “pop-up” events in different neighborhoods. But people can still comment online until at least Jan. 31, 2025.

PRT will share another draft of proposed changes they are calling “draft 2.0” with the public sometime this spring. The new draft will incorporate the feedback they are hearing at events and meetings like this one. Stops for the new routes have not been proposed yet.

“One of the changes proposed in the first draft that reflects changes in transit demand after the pandemic is the proposal to discontinue many of the commuter flyer routes,” Ms. Provonsha wrote in a Nov. 14 email. “The ridership on many of the commuter flyer routes remains very low and has not recovered after the pandemic. That being said, we will take another look at this based on public feedback we receive and refer to more recent ridership data as well. In the first draft, given our constraint of having the same operating budget and number of bus operators, we redistributed service hours from the commuter flyer routes and put them into standard bus routes that operate all day, 7-days a week, and this increased trips throughout the midday and on weekends for many of our local bus routes.”

Ben Nicklow, a senior planner at PRT, listed and explained the new routes that would go through Hazelwood: D44, D52, and O53. A fourth route, N94, skirts the edge of Hazelwood. He also mentioned X50, which follows the route of the existing 61C route; and O50, which follows the route of the existing 61D. Those two routes do not go through Hazelwood, but they have stops near Hazelwood and could be reached by transfer.

“You will be able to connect to [X50] through the Waterfront,” Mr. Nicklow explained. “When you need to go somewhere in that service area, even if it looks like it’s not quite in the same travel corridor you do currently, it may come so often that even if you have to transfer it’s a quicker trip.”

Where Hazelwoodians are going

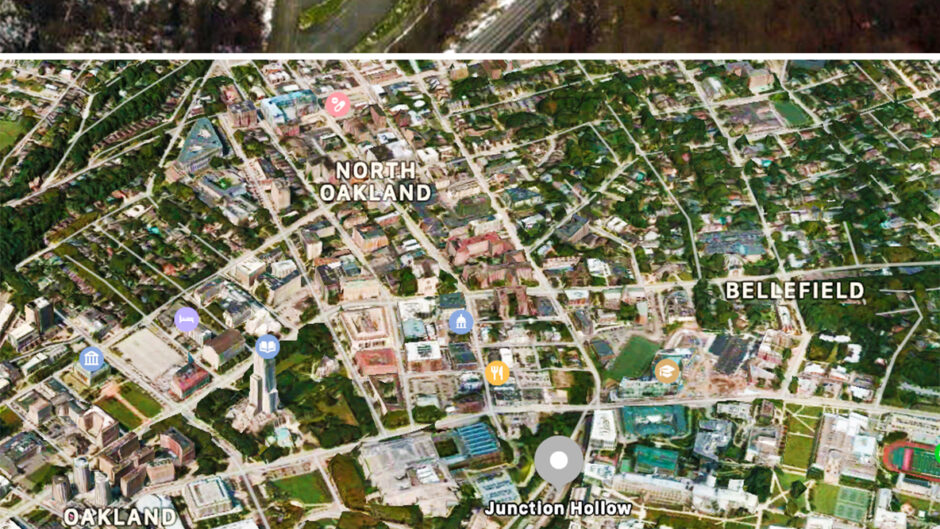

The team from PRT seems to have thought that Hazelwoodians travel to the Waterfront a lot more and to Squirrel Hill (along with other uphill neighborhoods) a lot less than they actually do.

When they took questions from meeting attendees, the questions centered mostly around the need for a direct connection between Hazelwood or Glen Hazel and Squirrel Hill. Attendees wanted one-seat rides to places other than Oakland and the Waterfront. Parents were concerned about their children getting to Allderdice.

Ms. Provonsha told me, “PRT recently held a stakeholder meeting in which we invited school Transportation Directors from all schools throughout the County to discuss their proposed changes and ask them to share data with us on where their students travel from to go to each school, so that we can compare those trips with the transit network.”

“I think they were surprised,” Ms. Taulton commented about the meeting. “I don’t think they realized the 93 was so critical, that people were using it to get to Squirrel Hill so much.”

She uses the 93 to get to work, do light grocery shopping, and get to her mom’s eye doctor, among other places. Hazelwood residents are going to Squirrel Hill not only for the necessities they lack in their own neighborhood, but for connections to the larger community.

Besides grocery stores and banks, Ms. Taulton and several other meeting attendees mentioned Zone 4 safety meetings in Greenfield and the JCC in Squirrel Hill. The JCC has the only pool nearby and offers activities for seniors. They also hold public meetings there.

Mary Bartol, who lives in Hazelwood, commented about the 93 at the Nov. 12 meeting.

“It satisfies every need we have because you can get off in Squirrel Hill to Schenley Park, then into Oakland — then you can go into Shadyside, get off anywhere there.” She said she sometimes visits Bloomfield and Lawrenceville and mentioned the new grocery store being built on Butler Street.

“We’d be lost without it,” Ms. Bartol said.

Lincoln Place PRT riders

Because PRT’s proposed changes are so complex and far-reaching, this article is one in a series. The next article planned is about Lincoln Place. Please email us at junctioncoalition@gmail.com if you want to be interviewed about how the bus line redesign would affect you.

You can review the Bus Line Redesign proposal, comment to PRT, and get the latest on meetings at PRT’s Bus Line Redesign website.

This article originally appeared in The Homepage.

Recent Comments