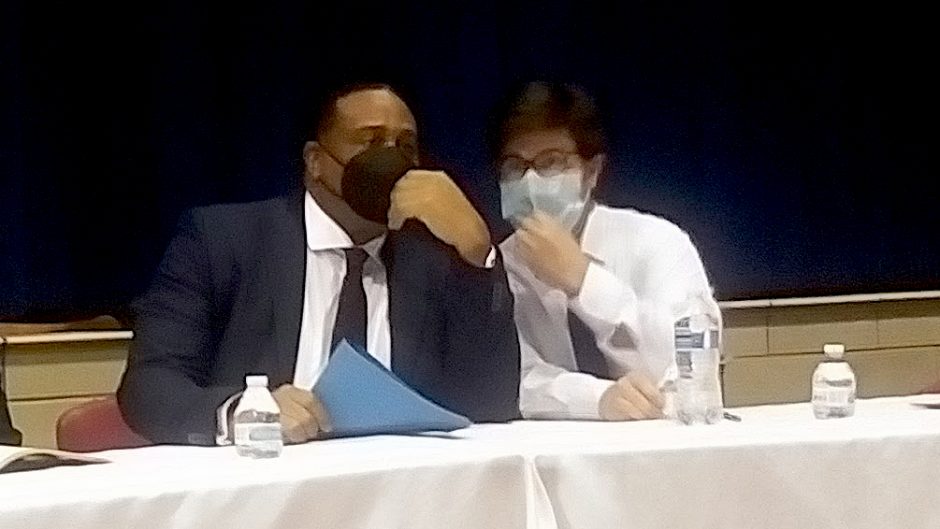

Pittsburgh’s Department of Mobility and Infrastructure (DOMI) held a public meeting on July 14 about the Swinburne Bridge project. Mayor Gainey’s neighborhood services manager, Rebekkah Ranallo, debuted as a co-facilitator.

Ms. Ranallo seemed genuinely excited to learn that about 20 residents of Four Mile Run (“The Run”) and their friends had gathered at their local pub to participate as a group in the Zoom-only meeting. “I think it’s great that folks are getting together for civic engagement opportunities like this,” she said.

During the Q&A session, attendees brought up a list of community demands (listed below) for a transparent public process. Ms. Ranallo assured them on behalf of DOMI and the mayor’s office, “We want to let you know that improving the way all of our departments do community engagement with our residents is a top priority.”

As the City of Pittsburgh begins “engaging” communities about this project, it’s important to understand why getting involved is a matter of survival for affected residents—and how they lost trust in local institutions tasked with serving the public interest.

A long history of deceit

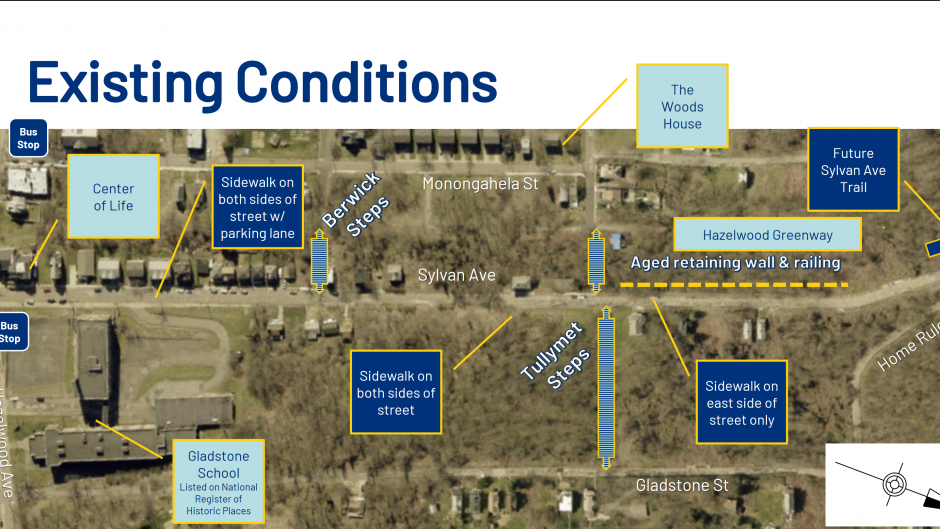

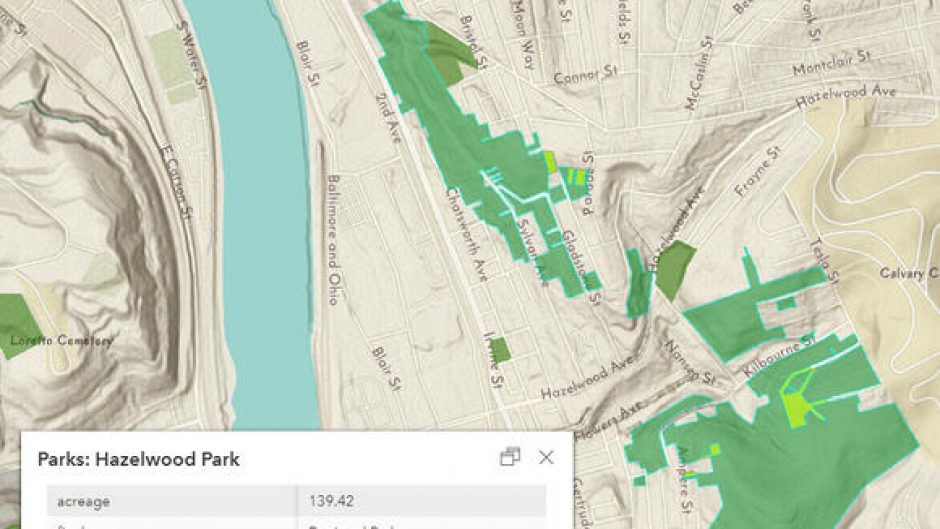

Residents of The Run, along with their neighbors in Hazelwood and Panther Hollow, have so far prevailed in a seven-year battle against private interests’ attempts to erase existing communities in support of the Hazelwood Green development using city funds and authority.

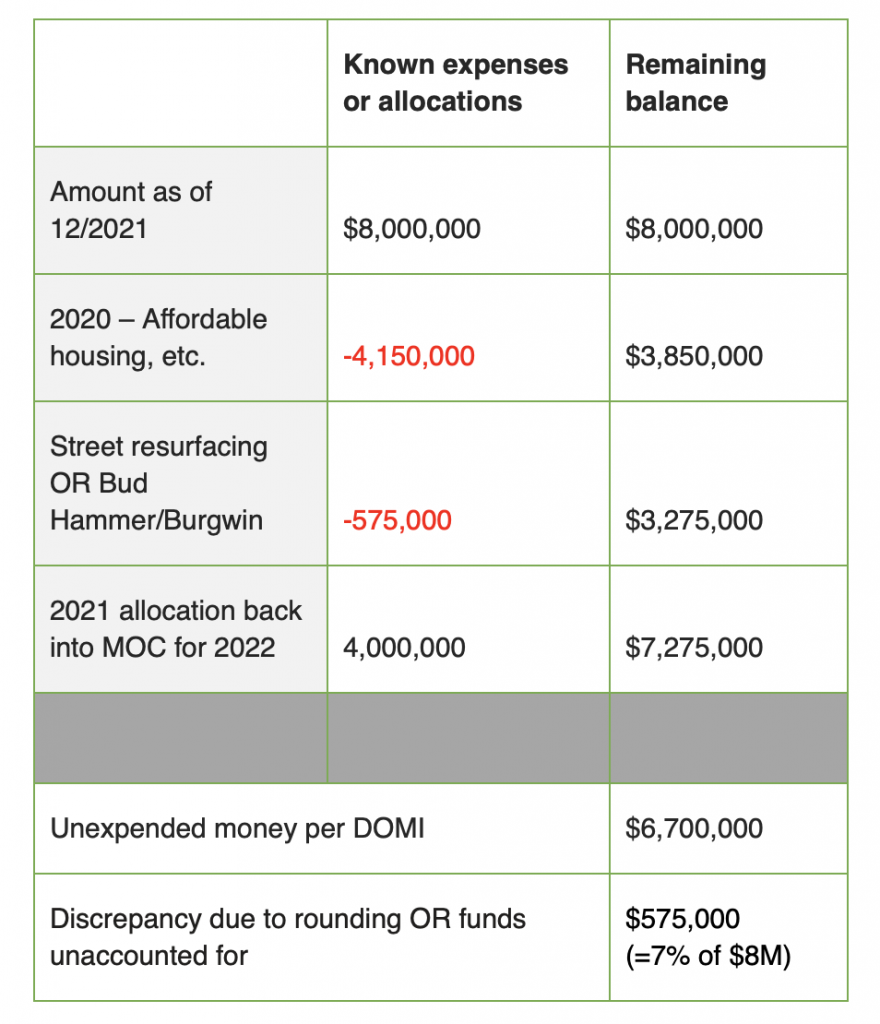

In August 2015, Run residents learned of Mon-Oakland Connector (MOC) shuttle plans from a Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article touting an already-submitted grant application that turned out to be fraudulent. DOMI, created in 2017, initially claimed they were pushing the restart button on the MOC concept. But the restart got off to a bad start when DOMI organized a January 2018 public meeting to “share the potential alternative routes” for the MOC. Attendees reported that the exercise seemed designed to herd them toward a conclusion that only the Schenley Park route could work.

Over ensuing years, DOMI continued pushing the MOC on affected communities in a dishonest and non-transparent way. These are just a few examples:

- On April 13, 2018, DOMI filed for a $1 million grant for work on the Sylvan Avenue trail, part of the MOC route, to make the trail suitable for MOC shuttles. At a public meeting the following month on May 22, DOMI did not mention the grant at all. When the grant was approved in July 2018 by the Southwestern Pennsylvania Commission, DOMI still did not inform affected residents. Asked about the grant and why DOMI kept it secret from residents, former DOMI director Karina Ricks said, “Well… we could have handled that better” and “It’s not possible for there to be some conspiracy—we’re just not competent enough for that.”

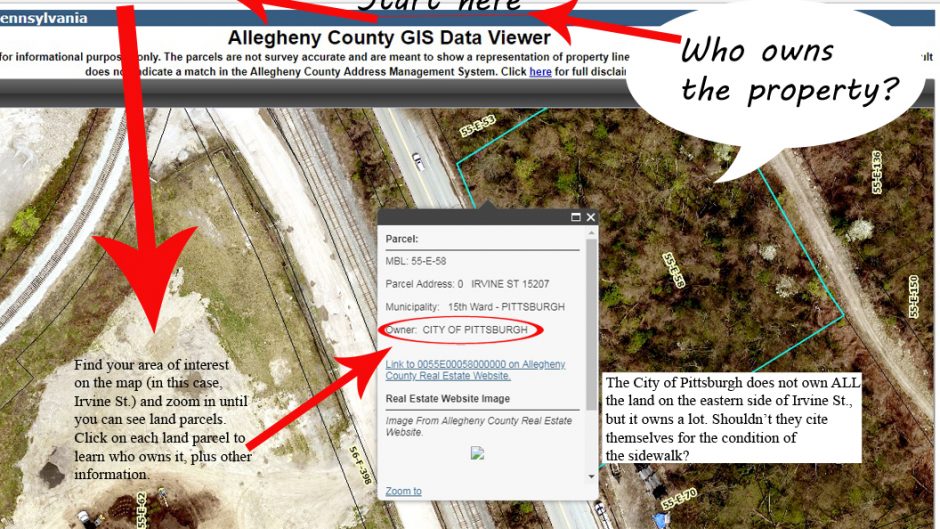

- In August 2020, residents on Acorn Street near the Swinburne Bridge received a letter from DOMI and AWK Consulting Engineers citing eminent domain. When asked about this at the October 2020 MOC meeting, Ms. Ricks responded, “It is a letter written by a lawyer and, unfortunately, they do reference the right of eminent domain. The City has absolutely no intention to take properties [as part of the bridge construction]. There is a possibility there might be some slivers that will be needed to create new footings for the bridge.”

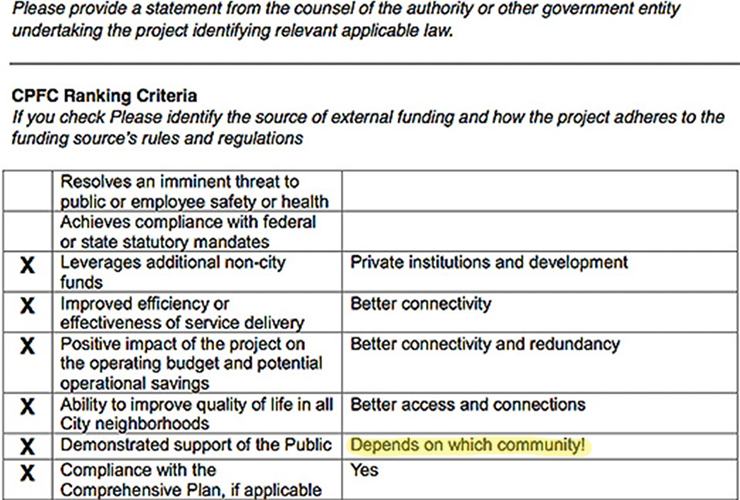

- Residents obtained a 2018 request from DOMI to Pittsburgh’s Office of Management and Budget for funding. That document is mostly blank, but DOMI was nonetheless given $9 million of taxpayer funds. One section of the document DOMI did fill out was the section reading: Please identify the source of external funding and how the project adheres to the funding source’s rules and regulations. “Demonstrated support of the public” was a checklist item within that section. DOMI checked off this item and commented: Depends on which community!

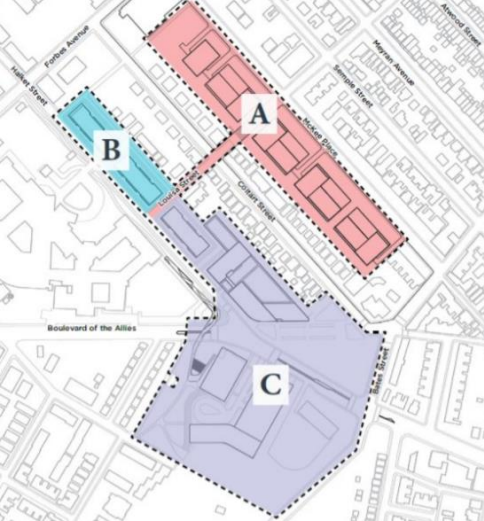

Additional information received through resident-filed Right-to-Know requests, sources in city government, and expert independent consultations revealed the true “vision” behind the MOC and the nature of Hazelwood Green’s relationship to surrounding communities. Private interests have a long-term plan that calls for erasing The Run off the map so universities can expand from Oakland campuses to Hazelwood Green. And it includes using eminent domain to acquire resident homes and business.

A 2009 study from the Remaking Cities Institute of Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), Remaking Hazelwood, makes this intention clear:

“The urban design recommendations proposed in this document extend beyond the boundary of the ALMONO site. The end of Four Mile Run valley, the hillside and Second Avenue are all critical to the overall framework. Some of these areas are publicly-held; others are privately-owned. A map is in the section Development Constraints. The support of the City of Pittsburgh and the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) will be critical to the success of our vision. The ALMONO, LP could try to purchase these sites. Failing that, the URA can support the project by purchasing those properties that are within the scope of the recommendations and making them available for redevelopment in accordance with the proposed strategy.”

Remaking Hazelwood, page 45

Unfortunately for existing communities seen by the authors of this report as “development constraints,” there is no evidence that underlying goals have changed for development in the area.

Another “restart button?”

Ms. Ricks left DOMI after Ed Gainey, who vowed to stop the MOC, won Pittsburgh’s 2021 mayoral race. Mayor Gainey announced the end of the shuttle road during a February 17 community meeting in Hazelwood, but DOMI has continued prioritizing MOC-related projects above longstanding infrastructure needs and dangerous traffic conditions in Greenfield and Hazelwood.

Public meetings about these projects have not shown improvement, either. DOMI originally scheduled the Swinburne Bridge meeting for June 16, but residents pushed back after finding out only 10 days in advance. The extent of DOMI’s outreach for that original meeting was a letter sent to a few residents, which those residents received on June 6. The rest of the community learned of the meeting through their neighbors who received the letter.

During a month-long lead-up to the rescheduled meeting, several residents asked DOMI to make the presentation (which they presumably would have prepared for the June meeting) available so the public would have time to review it in advance. None of the residents received a direct response from DOMI. About four hours before the start of the July 14 meeting, project manager Zachary Workman posted a statement in the Q&A section of the project’s Engage PGH webpage that DOMI would not honor the request.

Community demands shaped by experience

Residents have learned from years of MOC public meetings designed to check a “community engagement” box while minimizing the community’s effect on predetermined outcomes. The whole time, they were communicating ideas for better public engagement to DOMI—but DOMI ignored them. Residents have called for the following:

- All meetings must be posted with a minimum of 14 days’ notice to allow working people to arrange their busy lives to attend and have their voices heard. The meeting information must be widely advertised on social media, sent to email lists, and communicated by any means necessary to community members who lack internet access.

- The meeting presentation must be posted at the same time the meeting is announced. The public must be afforded sufficient time to review and understand the information being presented so they can come to the meeting prepared with questions. If you do not yet have the presentation ready, then you should postpone the meeting to give people a chance to review the presentation after you have posted it.

- All meetings must include a Q&A session where every attendee is able to hear all questions asked and all answers given. The Q&A session itself should be expected to last at least an hour, if not two hours. All answers to questions should be thorough and truthful, with a clear plan for following up on information DOMI doesn’t have. The Q&A session must not be curtailed because of time constraints, especially if the presentation has taken up more than half the allotted time for the meeting. There is no reason the presentation should require so much time, especially since the public will have already had a chance to review it. Dialogue with the community should be the main focus of all meetings.

- Meetings must offer an in-person option so that no community members are excluded.

- Meetings with a virtual component must provide space for at least 300 virtual attendees so that no one is unable to access the meeting at any time.

- After the meeting, a recording of the Zoom meeting and the chat transcript must be made available on the Engage PGH website.

Ms. Ranallo said at the July 14 meeting, “While I can’t speak to each item on your list of demands, we do want to build trust with you … We have a new administration, we have new leadership at DOMI, and we ask that you give us a chance to try to earn that trust.”

The community’s demands were compiled as a road map the city can follow to do exactly that.

Recent Comments