In late 2018, Pittsburgh City Council passed an ordinance that is birthing a system of Registered Community Organizations (RCOs). According to the City of Pittsburgh’s website, this new system gives RCOs “a formal role in the current development projects [taking place in a neighborhood] as well as neighborhood planning processes.”

Community organizations that want to become RCOs must meet criteria that include:

- Being a 501 (c)(3) nonprofit.

- Maintaining a website and posting public meeting agendas, minutes, and decisions.

- Holding two public meetings each year in an Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) accessible space.

- Submitting a signed letter from their City Councilperson.

Critics point to the financial and political resources needed to satisfy these requirements. Obtaining 501 (c)(3) nonprofit status can take months or even years. Although recent updates to the process allow some organizations to file a shorter form, the IRS will reject forms with any mistakes. Filing the form requires an online payment. Organizations may lack the funds to maintain a website or secure an ADA-accessible meeting space. And, critically, organizations at odds with their City Councilperson may find themselves shut out of RCO status.

According to a Dec. 3, 2018, Public Source article, president and CEO of the Hill Community Development Corporation Marimba Milliones described the required letter from a city council member as “an infringement of free speech.”

“Anyone who’s done any level of community organizing knows that a core part of community organizing is being able to go and articulate your issues to whomever, however…without retribution,” Ms. Milliones said at a community meeting. “And to give any elected official or any person the power to essentially endorse you as the voice for your community is unacceptable.”

The City speaks from both sides of its mouth on the issue, insisting that it “values the contributions that community organizations bring to our city and holds each in equal regard” while also saying “RCOs will receive certain benefits, not favoritism” compared to non-RCO groups. The benefits in question, obtainable only by jumping through the above-referenced hoops, lead to elevating well-connected professional community organizers above grassroots organizations with fewer resources or with interests that go against those of developers.

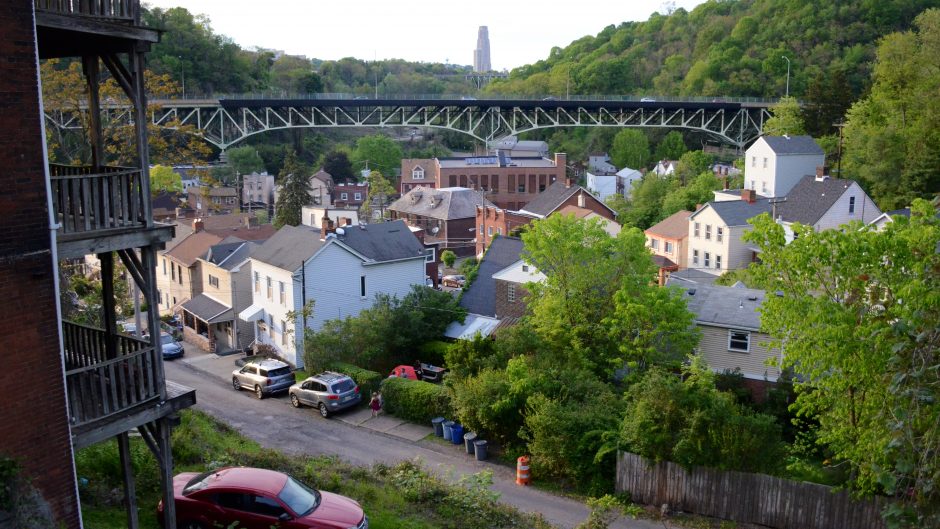

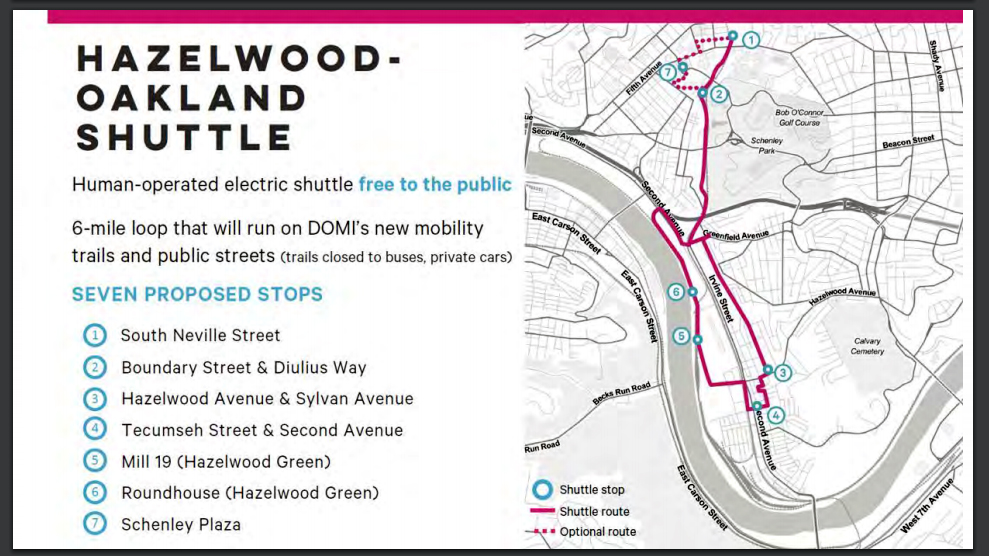

Outcomes of this new layer between average Pittsburghers and civic participation could prove dire in neighborhoods slated for big development projects by powerful interests. The proposed Mon-Oakland Connector (MOC) shuttle road through The Run is a prime example.

The Run, technically part of the Greenfield neighborhood, is geographically isolated from the rest of that community. Neither the MOC nor severe flooding in The Run affect upper Greenfield. One Greenfield Community Association (GCA) board member told GCA meeting attendees that the organization “does not represent the people of Greenfield.” Yet the GCA is currently in the process of acquiring RCO status and will become the de facto representative of the entire neighborhood—including The Run—in matters of community development.

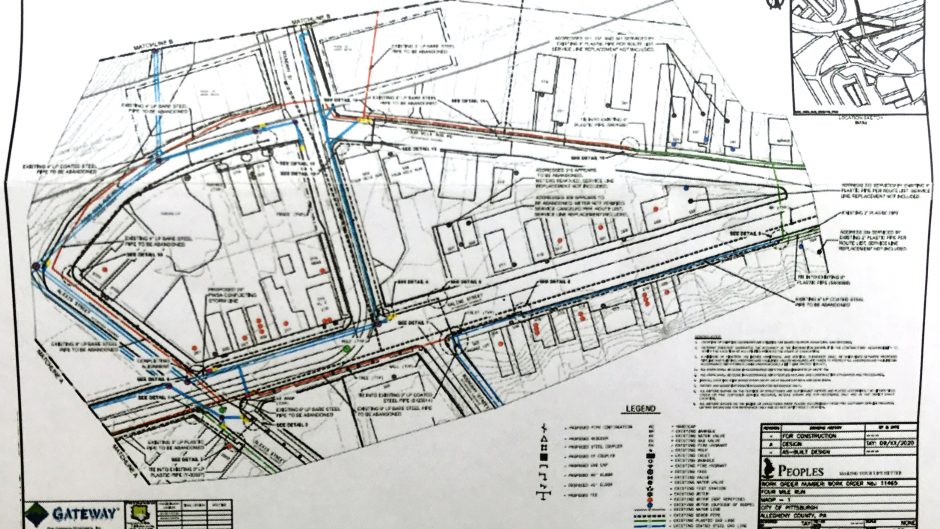

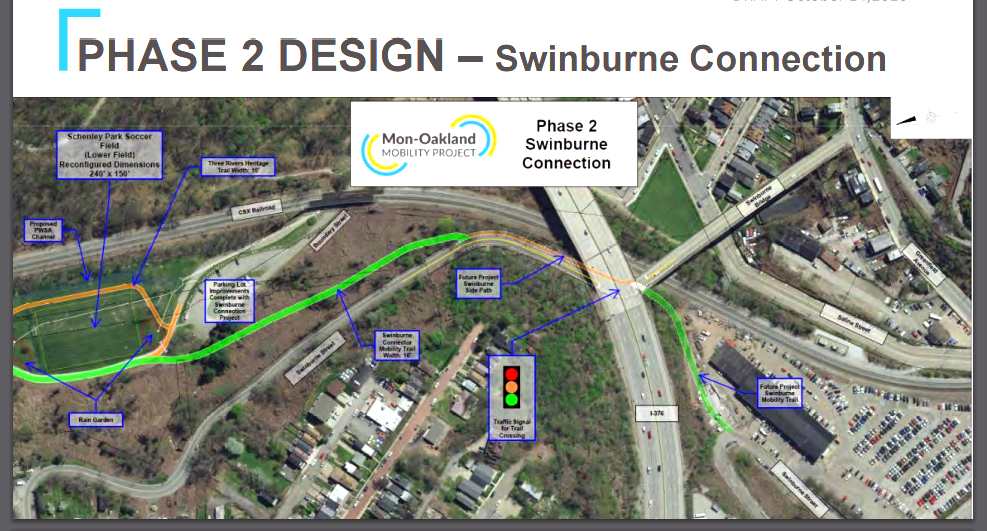

This leaves Run residents in a tenuous position. The GCA, which includes a tiny minority of Run residents, can easily ignore or compromise on issues concerning the MOC and combined sewer overflows to avoid ruffling feathers in city government. Run residents cannot afford to do so. A 2017 City-mandated survey of Run residents showed overwhelming opposition to the MOC roadway and unanimous demand for effective flood relief. Furthermore, part of the MOC plan calls for seizing several Acorn St. properties through eminent domain to widen Swinburne Bridge and make a dedicated lane for MOC shuttles.

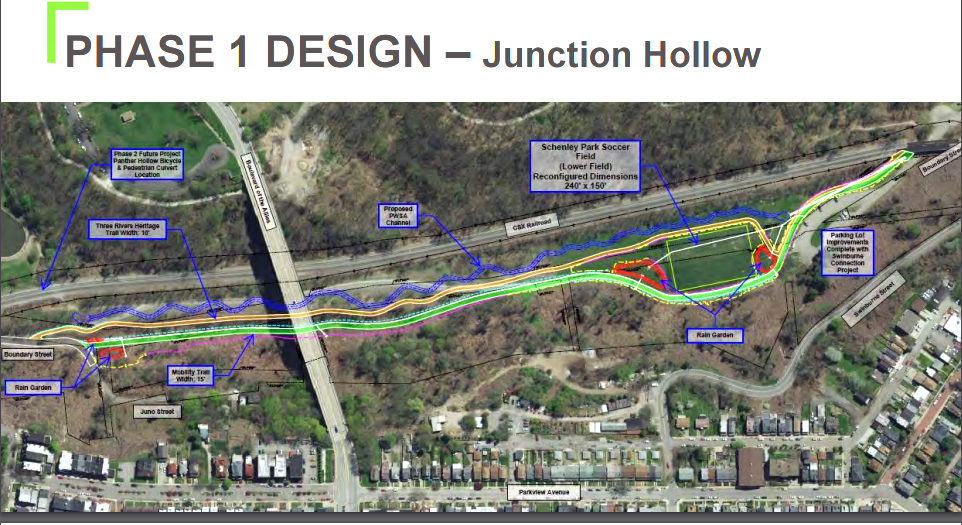

Residents of The Run and surrounding communities created the Our Money Our Solutions (OMOS) infrastructure/transportation plan to address the needs of existing residents. The group identified the needs of each community together rather than acting as individual neighborhoods in a void. In this way, they avoided “solutions” that could harm surrounding communities.

The OMOS plan is an example of how communities can unite to address their own needs—as opposed to the top-down, chainsaw development approach Pittsburgh has historically favored.

Requiring developers to address the community with their plans makes sense; however, the devil is in the details. Putting a nice face on rubber-stamping, bulldozing on behalf of outside interests, and rigging the game further entrenches these same old techniques of destroying healthy communities for profit. There are fairer ways to ensure that developers pass through a community approval process.

If you are concerned about the role of RCOs, start by finding out if your community has one. If your research or participation shows that the local RCO does not serve the interests of your community, you have a lot to consider. You may wish to form your own RCO—or work toward replacing the RCO framework in Pittsburgh.

Recent Comments