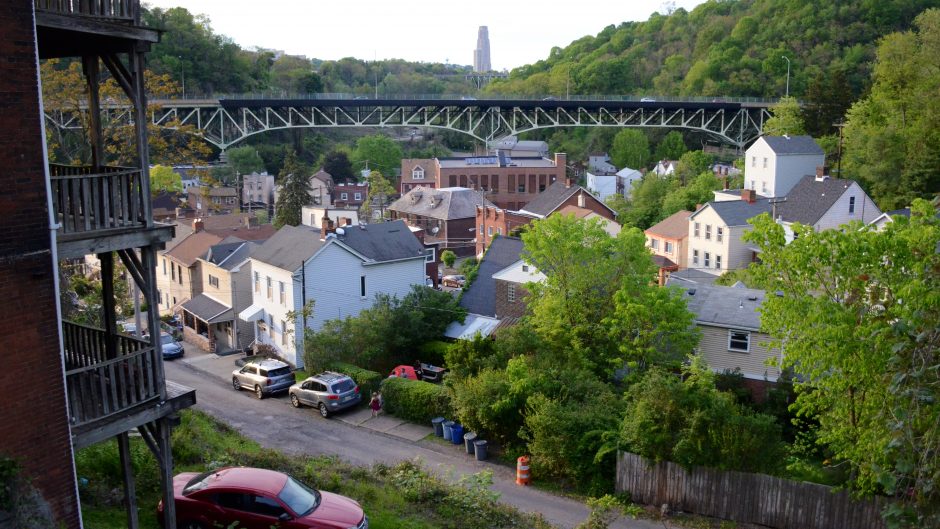

Greenfield Avenue’s 300 block needs traffic calming now

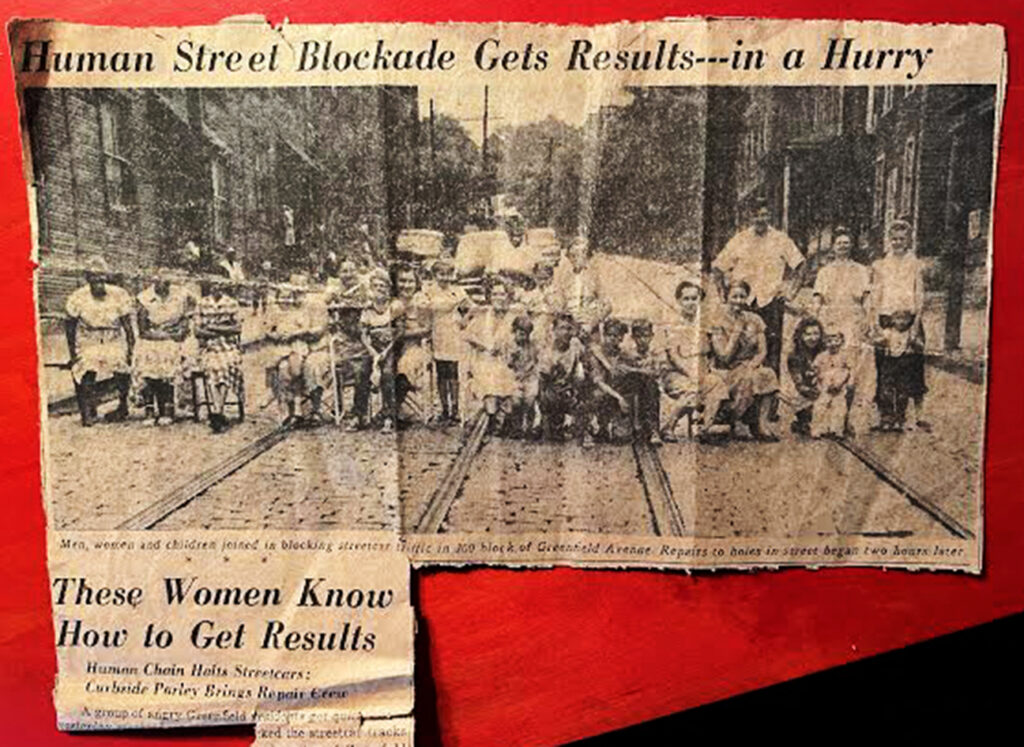

Residents along Greenfield Avenue’s 300 block were fed up with dangerous conditions on their street. Speeding vehicles and crumbling infrastructure caused wrecks and injuries, countless near-misses and a constant fear for children’s safety. Years of pleading with city officials to address the hazards went unanswered, so residents organized a protest. They brought their porch chairs and lined up across both lanes, shutting down all traffic on Greenfield Avenue. It was 1948.

Residents’ direct action that day caused officials to show up within two hours, repair the infrastructure and commit to policing speeding drivers. One of the organizers, Julia Grezmak, was my grandmother. Seventy-six years later, living on the block and experiencing these dangers every day, my neighbors and I feel the same frustration and outrage.

Past becomes present

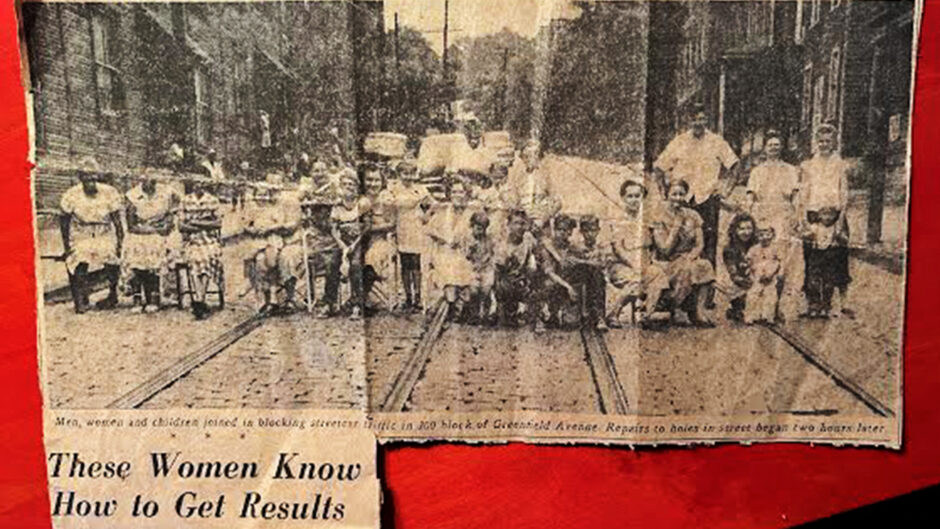

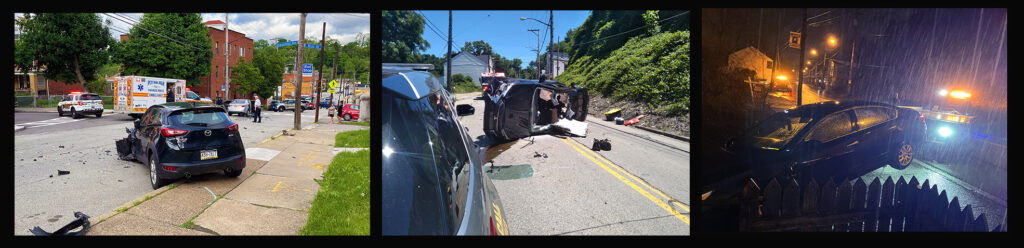

Today’s city officials are inflicting the same disregard on current residents. In the last decade, numerous legally parked cars on the block have been totaled. Clipped mirrors, sideswipes and other damages by hit-and-run drivers are commonplace. Worse, residents’ and pedestrians’ physical safety is at risk 24/7. Weekly near-misses that could cause severe injury or death take a mental and emotional toll.

The critically unsafe conditions on the 300 block are well-documented, but the city continually ignores our urgent, legitimate concerns.

Since 2014, we have been requesting traffic safety measures. In 2017, we began calling for the Department of Mobility and Infrastructure, known as DOMI, to meet with us onsite to witness the danger, discuss solutions and schedule resident-approved fixes.

A 2023 petition drive demanded DOMI address three areas of Greenfield Avenue needing traffic safety improvements. The city recently committed to addressing two of them, both in upper Greenfield. The 300 block, a notorious danger zone, was included in the petition. But — incredibly — DOMI left it out of Greenfield’s hard-won traffic-calming plan.

DOMI hedges as conditions worsen

My neighbors and I are furious at again being ignored while living on the most treacherous stretch in the neighborhood. This persistent, purposeful neglect over years amounts to abuse.

Since the closure of Anderson Bridge over Schenley Park, speeding has gotten worse as impatient commuters are detoured from both directions onto Greenfield Avenue. More than ever, crossing the street or exiting a parked car is a life-or-death game of chance.

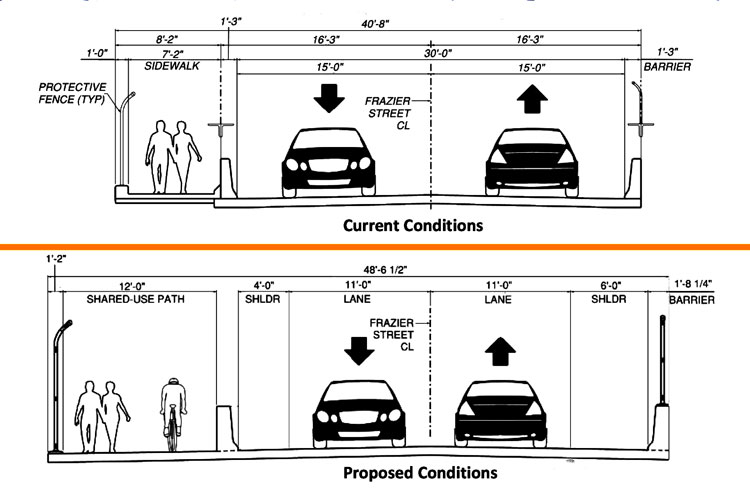

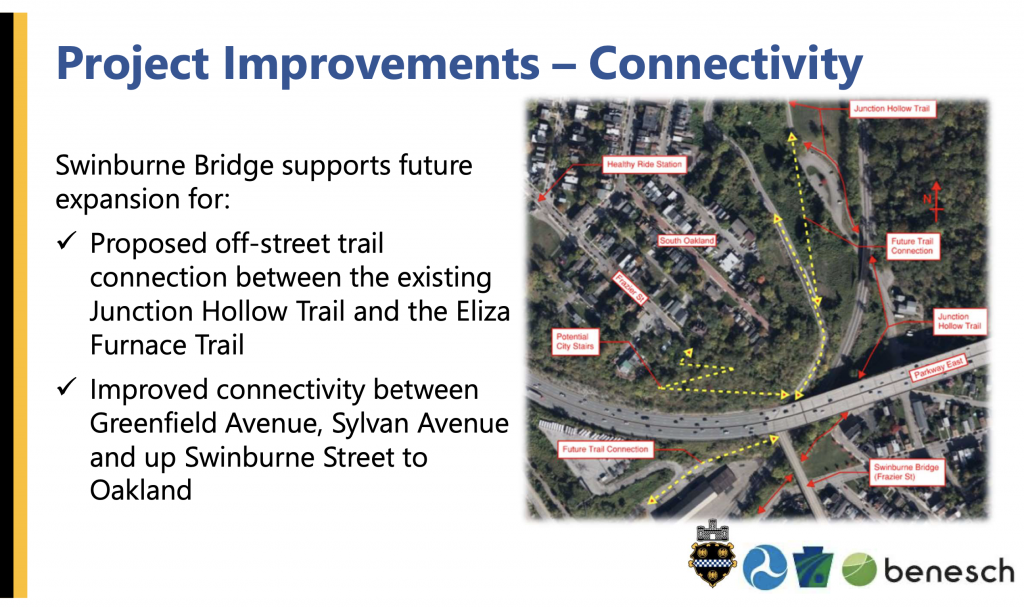

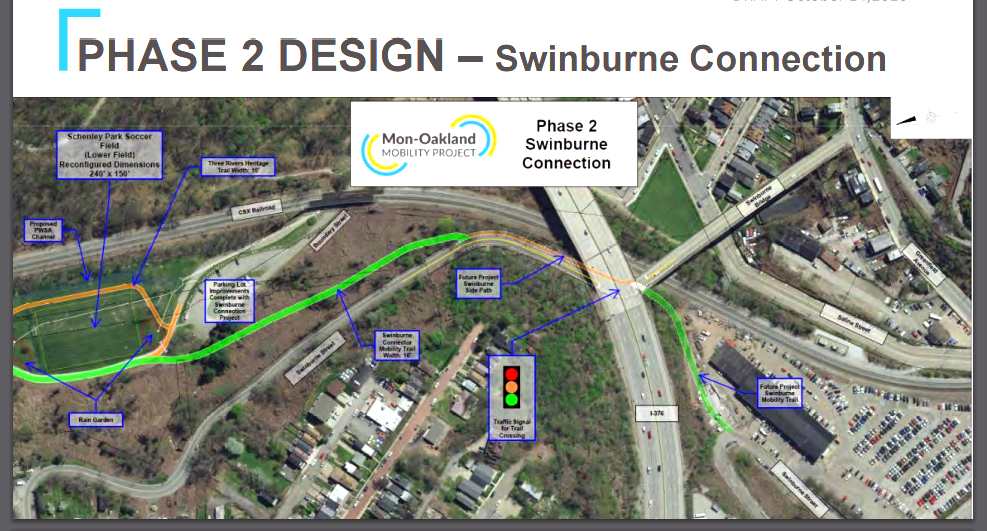

DOMI’s single proposal: a four-way traffic light at Swinburne Bridge. They won’t install it until after completely rebuilding the bridge, an extensive project that can’t even begin until work on Anderson Bridge ends. A traffic light could make the intersection at the bridge safer, but will do nothing to curb speeding on the 300 block.

Once past that intersection, eastbound drivers floor it, reaching 40-50 mph on the 25-mph residential street. Westbound drivers would have a clear path to speed downhill until reaching the bridge. A traffic light would accomplish nothing for safety on the 300 block.

DOMI has responded to our concerns and proposed traffic-calming solutions for the block with a mixture of arrogance, indifference and dismissiveness. After we confronted them at several public meetings, they said, “DOMI is aware of dangerous traffic conditions along Greenfield Avenue that led to repeated requests for traffic-calming measures … It’s in the long-range plans as resources become available.”

Resources are available… for now

Pittsburgh’s approved 2024 capital budget includes a 138% increase for traffic-calming measures, which amounts to $877,744 in additional funds. Residents’ ideas for solutions are chump change in this context. We have offered to provide the labor for installation to prevent delay and save taxpayers’ money.

If there is no traffic calming along the 300 block in 2024, the city may not fund it for years — or at all. At a public budget meeting on Oct. 4, city representatives projected a severe drop in revenue after 2024. They said the 2025-2027 budgets will be tight.

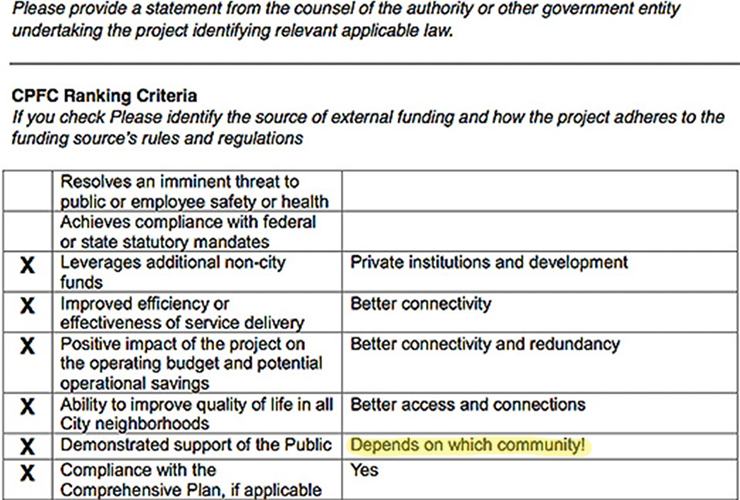

Representing corporate interests

We believe DOMI’s targeted refusal to address basic public safety needs stems from the wishes of private developers.

The foundations that own Hazelwood Green, along with CMU and Pitt, joined forces in the development plan through a public-private partnership announced in 2015. The Remaking Cities Institute’s 2009 “Remaking Hazelwood” report baldly stated their infrastructure goal: to move traffic as quickly as possible between Oakland and Hazelwood. Their report also advanced the controversial Mon-Oakland Connector, rejected by a multi-community coalition and canceled by Mayor Ed Gainey on Feb. 17, 2022.

These developers want infrastructure designed for their project rather than the safety of residents and pedestrians. It’s our public servants’ job to correct the power imbalance.

The city has publicly acknowledged that the 300 block qualifies for traffic safety improvements but chooses to prolong the danger and consciously disregard our personal safety. One neighbor dubbed it “vehicular terrorism.”

Direct action needed

If the Gainey administration is authentically committed to equitable traffic safety, they should put our money where their mouth is. After 76 years, the equitable thing to do would be to address unsafe conditions on lower Greenfield Avenue, now, before the next severe injury or fatality.

Residents on the 300 block are taking a stand. Unless DOMI commits to addressing our traffic hazards in 2024, we will implement our own safety measures to slow down drivers. It should not take causing an epic traffic jam to force officials to take adequate steps, but it might be the only way. I’m certain my grandmother would approve.

Recent Comments