On October 26, 2019, Junction Coalition received a response from DOMI director Karina Ricks to our open letter. In our letter, we asked questions compiled from residents of The Run—one of the neighborhoods in the path of the proposed Mon-Oakland Connector. After introductory comments, Ms. Ricks responded to the questions one by one. Below is the full, unaltered text we received. We formatted the response section with Ms. Ricks’ responses below each original question, along with our reply to each response.

Dear Junction Coalition,

Thank you for your message and providing an opportunity to respond and provide greater clarity around the Mon-Oakland and Four Mile Run project.

First of all, safety and health are the overarching concerns of this and any Administration. Project partners including the URA, Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy, PWSA and multiple City Departments have been working for years to effectively address the stormwater issues that impact the Four Mile Run portion of Greenfield.

Concurrently, economic regeneration in Pittsburgh is also a goal in order to both provide economic opportunity to our residents and put the City back on solid financial footing in order to have the resources to meet our many critical needs and public services. The Administration is committed to ensuring that this regeneration is forward-looking, promoting transit-oriented development and other sustainable mobility choices and avoiding the auto orientation and associated impacts of the past generation.

The Mon-Oakland/Four Mile Run project does both – it addresses the critical and threatening stormwater impacts and provides an opportunity for sustainable development and job growth in a community that very much needs both.

The attachment you sent – a URA grant application – emphasizes the stormwater project, seeking additional resources for design of stormwater mitigations, while concurrently recognizing the need for improved mobility and access. There is nothing in the grant to indicate that stormwater solutions are precluded by or subordinated to improved mobility. Clearly, both can be achieved.

1. We’ve been told that the watershed project and the roadway project are separate yet being done “in tandem.” That level of coordination requires detailed plans. When will you share full details so that resident-approved independent experts can evaluate them before construction begins?

- K. Ricks response: The City will share 30% design drawings for the mobility path and park amenities when complete. The anticipated timeline is 30% drawings by the end of the year, 60% drawings by the end of February and a complete bid package by spring.

- Junction Coalition reply: We look forward to seeing the materials you promised by the end of the year and will follow up. But design drawings are insufficient for any substantial evaluation. We have requested and continue to await the following:

- All up-to-date and current plans for the proposed road

- A drawing index plan of the overall Junction Hollow construction areas in Schenley Park

- Proposed plan drawings, engineering sections, and profiles of changes to Junction Hollow’s existing landscape

2. At the January 2018 public meeting, Michael Baker Corporation presented 6 possible routes (including 5 offered by residents). [DOMI director Karina Ricks] expressed a preference for the Swinburne route but said it was not viable because of the landslides on Swinburne. Why is Swinburne unviable for smaller lighter AVs, yet currently open to at-times bumper-to-bumper traffic including cars, trucks, UPMC shuttles, emergency vehicles, and school buses?

- K. Ricks response: The mobility path is to be an exclusive pathway suitable for both light shuttles and other e-powered vehicles such as e-bikes and, when categorized, e-scooters and other such vehicles as may evolve over time. There is insufficient width on Swineburn to provided this dedicated path. The street cannot be widened due to the fragile soil conditions.

- Junction Coalition reply: This answer only supports the need for our original question—and begs additional questions:

- How is it possible that these “light shuttles” and smaller vehicles named such as bikes and scooters require more width than the large vehicles such as school buses and UPMC shuttles that currently traverse Swinburne?

- Just how much width is needed for the proposed roadway and how can it be called a “trail” if it needs to be wider than a two-lane road for full-sized vehicles? In the maps you most recently presented at the Nov. 21 public meeting, the mobility road is marked as 15 feet wide. The narrowest part of Swinburne is an average of 19.8 feet wide.

- At the meeting, you mentioned vehicles that are 11 feet long and 6 feet wide. Two such vehicles could not pass each other on a 15-foot wide road while accommodating cyclists. Is DOMI considering widening the MOC road in the future?

3. The newest map shows the proposed roadway running right along the bottom of Swinburne, which has experienced landslides in the past and present, and which DOMI designated “unviable” as a route. What is the true reason you are so attached to the route through Schenley Park? Why do the private partners want this land so badly?

- K. Ricks response: There is an existing pathway through Junction Hollow at present. There is a former roadway (Boundary Street) and a current active freight rail line. This is a current and historic transportation/mobility corridor. The Mon-Oakland project is in keeping with this historic role.

- Junction Coalition reply: This response does not answer the original question. Don’t the Swinburne landslides have to be addressed in order to put a new road directly beneath the hillside as well as maintain the existing road on the hill? Regarding the history of Junction Hollow, the “former roadway” you mention was a poorly maintained dirt road. It was wiped out by, of all things, a landslide more than 30 years ago. That’s when the City closed it to traffic. The “current active freight rail line”—with trains carrying unidentified cargo (likely volatile fracking chemicals)—poses serious issues for the surrounding areas: not only our neighborhood but also the high-density residential housing in Oakland the rail line passes directly under. We should not add new potential hazards to the mix.

4. According to sources, there is a discussion happening behind the scenes about trying to buy out residents who live along Four Mile Run/Boundary streets—whose basements always flood when there is heavy rain. Is it true that you are going to attempt to buy or force those folks out through those or other means?

- K. Ricks response: There are no plans at present to buy residential properties in The Run. There are no plans to force residents out of their homes.

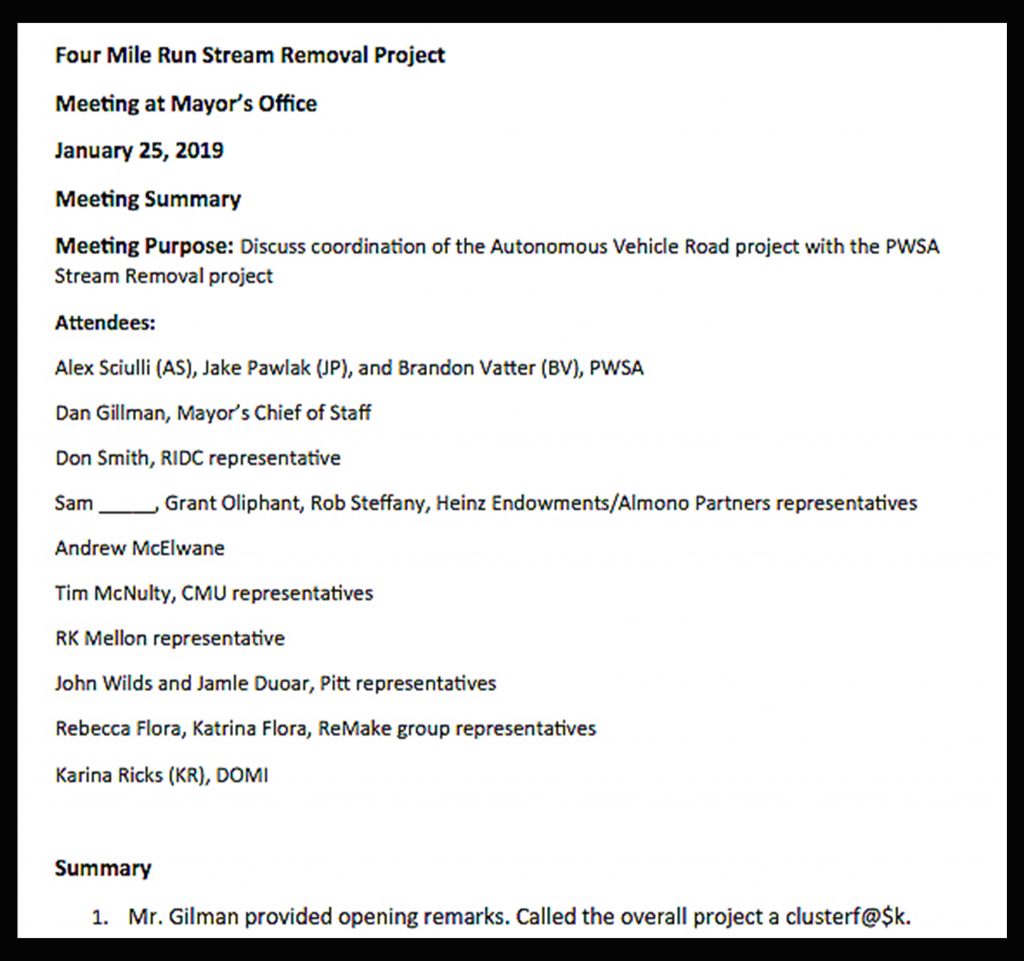

- Junction Coalition reply: “At present” is not a reassuring qualifier. At a 2/22/19 Mayor’s office meeting you attended, Alex Sciulli of PWSA “indicated people are going to expect with the project dollars spent that they won’t have flooding. [He] noted more cost-effective options may be to change the floodplain and purchase the affected properties.” (Quote sourced from meeting notes attained via Right-to-Know request to PWSA)

5. In 2015, public officials stated to the press that the city would go to court to overturn Mary Schenley’s deed in order to seize the publicly owned and protected property of Schenley Park. Are you still planning on going to court to force that outcome?

- K. Ricks response: The property along Junction Hollow is a portion of Schenley Park. There are park roads and pathways throughout Schenley Park. There is no need to go to court for the proposed facility.

- Junction Coalition reply: Regarding your statement that “there are park roads and pathways throughout Schenley Park,” existing features do not justify creating a new road in an important established bike and pedestrian corridor. The Junction Hollow trail is part of the only connection between Oakland, Greenfield, Hazelwood, the South Side, and Downtown that does not require users to share a road with motorized vehicles. Moreover, the proposed road is specifically for privately operated vehicles, which goes against Mary Schenley’s original intent for the park as stated in her deed.

6. At the September 2018 meeting, PWSA head Robert Weimar stated, “We only have one chance to get this right” regarding the storm-water plan’s success. We agree, and expect access to detailed plans so that an independent, resident-approved expert can evaluate them before construction begins. When will you provide those plans?

- K. Ricks response: Please direct requests for the stormwater design plans to PWSA.

- Junction Coalition reply: At the City’s suggestion in response to our first Right-to-Know request, we directed these requests to PWSA via additional RTKs. PWSA gave us materials that seem to conflict with what DOMI has provided in its most recent public materials. Neither DOMI nor PWSA has given us current, adequately detailed plans for analysis.

7. Will you provide a list of all “project partners” with their contact information—email addresses and phone numbers?

- K. Ricks response: The project partners are: Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority led by Robert Weimar (rweimar@pgh2o.org), Department of Mobility and Infrastructure led by myself, Department of Public Works led by Mike Gable (mike.gable@pittsburghpa.gov). The Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy serves as a project advisor having completed the Four Mile Run Conceptual Design Plan. PPC is led by Jayne Miller. The URA and Department of City Planning are occasionally consulting parties to the project as is Hazelwood Green represented by Rebecca Flora.

- Junction Coalition reply: Thank you for providing this list, but the absence of private entities in your list leads to further questions. Does this mean University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University, the private partners named in the URA’s 2015 grant application (ID 2015073111048) are no longer involved in the project? Was the public-private partnership referenced in the grant application formally dissolved?

If so, and if the Mon-Oakland Connector/Mon-Oakland Mobility Project is a different project, then why does it have the same goals as the Oakland Transit Connector referenced in the 2015 grant application—and why do various private entities continue to act as stakeholders in meetings throughout the process while the public is invited to participate only in reviewing already-decided plans?

8. Multiple experts have told residents that forcing the roadway onto the watershed plan will compromise flood control. A URA document titled “Project Narrative for Heinz Endowment” states, “Measure of success: We will produce several construction alternatives … and couple them with the potential design options that will not preclude any major transportation options under discussion.” In plainer language, this paragraph says that a successful flood control plan won’t interfere with the proposed roadway—in other words, the road takes precedence. This directly contradicts repeated public statements made by you [K Ricks], PWSA, and other officials. Given the true priorities behind both projects, what guarantees can residents expect regarding the success of the watershed improvement plan? When will a community benefits agreement with those guarantees be enacted?

- K. Ricks response: The narrative above clarifies the misinterpretation that an effective stormwater solution is precluded by a supplemental pathway. [Following is the narrative we believe Ms. Ricks references here.]

The Mon-Oakland/Four Mile Run project does both – it addresses the critical and threatening stormwater impacts and provides an opportunity for sustainable development and job growth in a community that very much needs both.

The attachment you sent – a URA grant application – emphasizes the stormwater project, seeking additional resources for design of stormwater mitigations, while concurrently recognizing the need for improved mobility and access. There is nothing in the grant to indicate that stormwater solutions are precluded by or subordinated to improved mobility. Clearly, both can be achieved.

- Junction Coalition reply: Actually, it doesn’t seem clear at all. We have included relevant text below and you can reference the complete document.

Goal 3: We will create a feasible design for the area encompassing the southern area of Schenley Park to the Monongahela River. This particular design question is one of the more important and most technically challenging, and has the potential to provide the most impact to the overall question of whether a design that can truly integrate ecological/compliance goals and transportation connections is possible. It necessitates answering the question of whether a separate storm sewer from the southern end of the park to the river is feasible. But there is an extremely high amount of both above and below grade infrastructure– not to mention a high interest and need in creating multi-modal transportation connections– that requires a specialized approach to daylighting in this area (trenchless). Measure of success: We will produce several construction alternatives (such as horizontal directional boring, micro tunneling, etc.) and couple them with the potential design options that will not preclude any major transportation options under discussion.

To summarize, the project is “technically challenging” even without “a high interest and need in creating multi-modal transportation connections.” There is an overall question of whether “a design that can truly integrate ecological/compliance goals and transportation connections is possible.” But the success of the project will be measured by how well “construction alternatives” can be “couple[d]” with “the potential design options that will not preclude any major transportation options under discussion.”

The summary we provided here uses the actual language of the document and directly conflicts with the “narrative” you provided.

Your response also does not answer the questions we asked: What guarantees can residents expect regarding the success of the watershed improvement plan? When will a community benefits agreement with those guarantees be enacted?

9. How was it determined that the route through two neighborhoods and Schenley Park is the only viable route? Swinburne would have to be stabilized to prevent it from collapsing onto the proposed roadway. So why spend an additional tens of millions of dollars to build a new road instead of using Swinburne as the route?

- K. Ricks response: The response to question 2 should also answer this inquiry. Widening Swinburne Road is not feasible.

- Junction Coalition reply: This response does not answer the original question. It only brings up more questions, as detailed in our question 2 reply.

Moreover, your statement that “widening Swinburne is not feasible” does not make sense as the reason an existing road cannot serve as an alternative to a new road in Schenley Park. As detailed in our question 2 reply, the maps you most recently presented show the mobility road marked as 15 feet wide. According to your statements at the most recent public meeting on 11/26, this width necessitates shuttles pulling over to let another oncoming shuttle pass. The road is billed as accommodating commuter cyclists, yet it forces them into extremely close contact with motorized vehicles that frequently need to pull over. Swinburne St. is 19.8 feet wide on average at its narrowest point. It would seem that Swinburne is already significantly wider than the proposed road even at its narrowest, and therefore would not need to be widened.

In any case, “fragile soil conditions” on Swinburne endanger the proposed roadway as much as they endanger the existing street.

10. On April 18, some residents of The Run, along with Pittsburghers for Public Transit and the Penn Plaza Support and Action Coalition, sent Mayor Peduto an open letter. We made specific, actionable demands to actually include the public in this so-called public process concerning the Mon-Oakland Connector—things like announcing the meetings at least 14 days in advance, revealing the total amount of public funds spent so far, and formatting the meetings so that all attendees can hear all the questions and answers. When will we receive a formal response, and why are you continuing to take up most of these meetings with presentations and breakout sessions?

- K. Ricks response: Meetings have been and will be announced at least 14 days in advance. Meetings have been structured to provide time for people to engage in the means and methods most comfortable and accessible to them. This includes presentations with opportunities for written comments and feedback, whole group “plenary” discussion, small group breakouts, online information and feedback and occasionally field visits/tours and meetings with individual neighborhood organizations. While we recognize the preferred engagement method proposed by the Coalition, we also recognize that diverse individuals engage in a diversity of ways thus we will continue to provide engagement in multiple ways rather than the one means prescribed in your letter.

- Junction Coalition reply: Have you specifically asked for feedback about engagement methods? If so, how was this accomplished and do you have records of the results? How much preference did you receive in the feedback specifically for “small group breakouts?”

11. By choosing AV, you are eliminating jobs, thus reducing the tax base. How will the City make up for this loss of revenue and pay for basic services like roads, bridges, infrastructure, etc.? Will robots pay taxes?

- K. Ricks response: The Mon-Oakland Connector is a trail, not an operational service. The trail is being designed to accommodate use by microtransit. This service may one day be provided via self driving vehicles however at this point in time no truly self driving technology exists thus anyvehicles will have a human operator. There is a much larger policy discussion locally and nationally that is necessary around transportation funding (the current mechanism – the gas tax – is insufficient to support infrastructure maintenance and improvement, and gas tax revenues are projected to decline with greater fuel efficiency and electrification of the fleet). The future of work for the rising generation of workers is also a critical discussion. Fortunately full autonomy is still decades away and there is adequate time to prepare for a non-disruptive transition that preserves the ability for our workers to make a livable wage through dignified, rewarding work.

- Junction Coalition reply: So the road is being built for microtransit in general, not specifically for self-driving or automated vehicles? Regarding microtransit as a solution, we invite you to read this post from public transit consultant Jarrett Walker if you have not already done so. Why are we spending tens of millions of taxpayer dollars to build a road for privately operated microtransit that by its very nature serves a small group of people?

Your point that “any vehicles will have a human operator” because “full autonomy is decades away” means the service would essentially consist of a fleet of minivans (8,000 pounds, 11 feet long, 6 feet wide). Human operators can drive at higher speeds than 15 mph and they can travel on existing roads with other minivans. In other words, a foreseeable future of human shuttle operators undermines the rationale for an isolated corridor to accommodate a microtransit service. Even driven at normal speeds, the route through the park does not offer the dramatic shortcut originally proffered in 2015. Officials claimed commute times from Hazelwood to Oakland of 30-40 minutes, but this was based solely on rush-hour traffic. Residents stopwatch-tested the claim by driving existing routes at various times. The Second Ave.-Bates St. corridor from Hazelwood to the main campuses in Oakland took 12-14 minutes. Various existing routes from the intersection of Greenfield Ave and Saline and Irvine streets took 3-4 minutes to Hillman Library in Oakland.

Moreover, if “no truly self driving technology exists” and automated shuttles are a far-off eventuality, please explain why Pittsburgh worked to secure the Knight Foundation grant and why you are so eager to use it to bring autonomous vehicles to events where Pittsburghers can “kick the tires” as you said. Not to mention that Uber and others are already using Pittsburgh streets as a test track for their autonomous vehicles.

Your position in this response seems designed to have it both ways: The road must be built now for a far-off technology, and since DOMI is only building a road the service can be whatever is convenient at any given time to bolster an argument for building the road.

12. The Planning Commission approved a last-minute tripling of residential density in the Hazelwood Green plan over objections by the Greenfield Community Association and the Run Resident Action Team. Karina Ricks admitted in 2017 that if Amazon accepted Pittsburgh’s bid, the Mon-Oakland Connector would be inadequate for the increased number of users. Why are you investing public money into a roadway that is already obsolete before it’s even built?

- K. Ricks response: Additional trail capacity will never be obsolete. The City of Pittsburgh is hopeful to regain a substantial portion of the near 700,000 residents we once had (current city population is 305,000). We cannot support this regeneration if our restored residents drive at rates common among our existing regional residents. We must promote and encourage a greater share of trips being accomplished via walking, transit, bicycle, micromobility and higher occupancy vehicles like microtransit. If we are successful in accomplishing our goal of >50% of household trips being accomplished by non-auto and active transportation means we are going to need substantially more capacity for these modes throughout our city including along theJunction Hollow Trail corridor. Furthermore, we know that the best opportunity to form lasting travel habits is when a person moves to a new residence or new job location. Doing this means we need to make their initial experience easy, dignified, and maybe even fun. If we can “train” new workers and residents to take that initial ride even on the low speed, smaller capacity microtransit, we can convince the of the “proof of concept” that transit generally is a viable mode for everyday trips and we can create a life-long a low-drive resident or worker. High capacity mass transit will always be the long term goal. Microtransit, however, can be the way to attract more riders to our region wide system.

- Junction Coalition reply: Why do we so desperately need to increase the tax base by doubling our current population? Why not instead tax the corporations masquerading as non-profits? Public servants should not allow their constituents to be held hostage by powerful private interests. Furthermore, the utility of microtransit in benefiting the general population or attracting new residents is dubious.

13. Isn’t it a conflict of interest that some of the people involved in decision making about the roadway and storm-water projects stand to profit from developing Hazelwood Green?

- K. Ricks response: Please see response to question 7 and further clarify.

- Junction Coalition reply: Please refer to our reply to the same question. Again, the names you provided do not reflect the public-private partnership that originally filed a grant application for this project in 2015. Was this PPP formally dissolved? If this is truly a different project from the 2015 project, why does it have the same goals?

14. We have the agenda from a 2000 “community outreach project” meeting titled “The New Junction Hollow Vision.” The agenda advocates for a short, intense “charette” process—that means a meeting of all stakeholders where conflicts are worked out. But the meeting involved only residents of Oakland and the Oakland Community Council. Hazelwood Initiative is mentioned but not Panther Hollow or The Run—the neighborhoods that are actually located in Junction Hollow, the communities that would be affected most. Do the Oakland organizers of this meeting still think Junction Hollow belongs to them, and that they can decide its future? Why would they not include the communities of Panther Hollow and The Run?

- K. Ricks response: The document and meeting referenced are now nearly 20 years old and no longer being used as the basis of the current public engagement process.

- Junction Coalition reply: This answer willfully misses the point of the question. This roadway was being discussed 20 years ago and the directly affected communities were excluded. The 2015 grant application (before your involvement) violated the PA Sunshine Act. In other words, this project has a long history of secrecy and questionable conduct. More recently, new grant applications went unmentioned in all the public meetings that occurred as the applications were being prepared and filed. This is just one example of a sustained focus on the appearance of transparency at the expense of transparency itself. The “current public engagement process” does not seem to have changed all that much in 20+ years. Why have the communities of Panther Hollow and The Run been excluded for so long?

15. A URA document titled “Exhibit 1” states, “The implementation of the Oakland Transit Connector model can address a majority of these barriers and will open the opportunities for continued economic growth across Oakland and into adjoining communities.” The barriers: People already live here. There’s a public park here. Development can only address these “barriers” by eliminating them. No one consulted those “adjoining communities” about the Mon-Oakland Connector before deciding to proceed with it. And during the series of public meetings last year, DOMI filed another grant application connected to the roadway without telling residents. City officials have lamented the continuing distrust around this project, but how can they be surprised?

- K. Ricks response: Question is rhetorical

- Junction Coalition reply: The question is far from rhetorical to communities that face extinction as a result of decisions that are being made without their input—and further, to the detriment of their safety and quality of life.

16. Some people would like to attend these meetings but can’t because they are taking care of kids. Will you use part of the Knight Foundation grant to facilitate their participation by providing kids’ activities and supervision for future meetings?

- K. Ricks response: That is a great suggestion. We will see if that can work. If there is a member of the Coalition that would serve as a sounding board on a structure, time and activities that would be most conducive to this type of engagement, that would be wonderful.

- Junction Coalition reply: Barb Warwick has volunteered to act in this role. Please let us know if you do not have her direct contact information and we will provide it to you.

17. DOMI’s presentation for the February 2018 meeting included a chart that gave “Autonomous Microtransit” a higher positive ranking than conventional shuttle buses and improved Port Authority bus service. This despite the fact that no data supports the assertion that AVs have a greater ability to “deliver in the near term” or “promote sustainable mobility and development”—in fact, the proposed Mon-Oakland Connector requires completely new infrastructure and a new fleet of vehicles. Why is AV being so aggressively put forward as the solution and whose interests does this serve?

- K. Ricks response: Please see response to question 11.

- Junction Coalition reply: It is convenient to get around these questions by stating that you are only making decisions about the road itself—but if you have no idea what you are going to put on the road, how is that a transit solution?

18. Will people be able to use the Mon-Oakland Connector if they don’t have a smartphone or don’t want to provide personal information? What happens to the personal information a Mon-Oakland Connector app would collect?

- K. Ricks response: 18 and 19. Please see answer to question 11. When a service is proposed to operate on the trail these questions will need to be publically answered before a permit for operation will be granted.

- Junction Coalition reply: It is convenient to get around these questions by stating that you are only making decisions about the road itself—but if you have no idea what you are going to put on the road, how is that a transit solution?

19. What will happen to the Mon-Oakland Connector fare system after the fares are no longer subsidized (after 2 years)?

- K. Ricks response: 18 and 19. Please see answer to question 11. When a service is proposed to operate on the trail these questions will need to be publically answered before a permit for operation will be granted.

- Junction Coalition reply: It is convenient to get around these questions by stating that you are only making decisions about the road itself—but if you have no idea what you are going to put on the road, how is that a transit solution?

Recent Comments